Report: Racism

New Perspectives on Race and

Ethnicity

Part 2

Desegregation and Resegregation in the

Public Schools

The Racial Gap in Academic Achievement

Schools That Work for Minority Students

Preferential Admissions in Higher Education

==============================

Hoover Institution

http://www-hoover.stanford.edu/publications/books/colorline.html

Beyond the Color Line: New

Perspectives on Race and Ethnicity in America

Edited by Abigail Thernstrom

and Stephan Thernstrom

Hoover Institution Press Publication No. 479

2002

==============================

Abstract

From color-blind to color-consciousness—a counterproductive approach to racial equality?

The American racial and ethnic landscape has been radically transformed over the past three decades. A generation ago, blacks had much less education, much poorer jobs and were more likely to live in solidly black neighborhoods than they are today. Yet the old notion of “two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal” still persists thirty years after it first appeared in the misguided diagnosis of the Kerner Commission report.

America’s changing racial and ethnic scene is the central theme of Beyond the Color Line. In essays covering a range of areas including education, law, religion, immigration, family structure, crime, economics, politics, and more, this volume examines where we’ve been, where we are, and where we’re going. Along the way, the authors attempt to illuminate how we have moved from Dr. Martin Luther King’s dream of all Americans being judged solely by the “content of their character, not the color of their skin” to today’s vaguely Orwellian civil rights orthodoxy—that it is necessary to treat some persons differently in order to treat them “equally.”

The product of the Citizens’ Initiative on Race and Ethnicity—formed in 1998 as an alternative to the one-sided official “dialogue” on questions of color—many of these twenty-five brief essays offer either explicit or implicit public policy recommendations. A common theme unites them—new realities require new thinking, and old civil rights strategies will not solve today’s problems. Beyond the Color Line takes the first steps toward a new civil rights agenda.

Abigail Thernstrom, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a member of the Massachusetts State Board of Education since 1995, and Stephan Thernstrom, the Winthrop Professor of History at Harvard University and Manhattan Institute senior fellow, are coauthors of America in Black and White: One Nation Indivisible (Simon & Schuster, 1997) and write frequently for a variety of journals and newspapers, including The New Republic, the Wall Street Journal, and the UCLA Law Review.

Contributors: David J. Armor, Michael Barone, Douglas J. Besharov, Clint Bolick, David Brady, Linda Chavez, William A.V. Clark, Ward Connerly, John J. DiIulio Jr., Tamar Jacoby, Everett C. Ladd, George La Noue, William J. Lawrence, Nelson Lund, Christine H. Rossell, Sally Satel, Thomas Sowell, Shelby Steele, Abigail Thernstrom, Stephan Thernstrom, Martin Trow, Reed Ueda, Eugene Volokh, Finis Welch, James Q. Wilson, C. Robert Zelnick

==============================

Table Of Contents

Foreword ix

John Raisian and Larry Mone

Contributors xi

Introduction 1

PART ONE THE BIG PICTURE

The Demography of Racial and Ethnic Groups 13

Stephan Thernstrom

copyright © 2001 by Stephan Thernstrom

Immigration and Group Relations 37

Reed Ueda

What Americans Think About Race and Ethnicity 53

Everett C. Ladd

Wrestling with Stigma 69

Shelby Steele

PART TWO PRIVATE LIVES AND PUBLIC POLICIES

Residential Segregation Trends 83

William A. V. Clark

African American Marriage Patterns 95

Douglas J. Besharov and Andrew West

Crime 115

James Q. Wilson

Health and Medical Care 127

Sally Satel

Supporting Black Churches 153

John J. DiIulio Jr.

PART THREE ECONOMICS

Discrimination, Economics, and Culture 167

Thomas Sowell

copyright © 2001 by Thomas Sowell

Half Full or Half Empty? The Changing Economic Status of African Americans, 1967–1996 181

Finis Welch

Discrimination in Public Contracting 201

George R. La Noue

PART FOUR EDUCATION

Desegregation and Resegregation in the Public Schools 219

David J. Armor and Christine H. Rossell

The Racial Gap in Academic Achievement 259

Abigail Thernstrom

copyright © 2001 by Abigail Thernstrom

Schools That Work for Minority Students 277

Clint Bolick

Preferential Admissions in Higher Education 293

Martin Trow

PART FIVE LAW

Racial and Ethnic Classifications in American Law 309

Eugene Volokh

copyright © 2001 by Eugene Volokh

Illusions of Antidiscrimination Law 319

Nelson Lund

PART SIX POLITICS

Race, Ethnicity, and Politics in American History 343

Michael Barone

The Politics of Racial Preferences 359

David Brady

From Protest to Politics: Still an Issue for Black Leadership 369

Tamar Jacoby

PART SEVEN ONE NATION, INDIVISIBLE

The New Politics of Hispanic Assimilation 383

Linda Chavez

In Defense of Indian Rights 391

William J. Lawrence

The Battle for Color-Blind Public Policy 405

C. Robert Zelnick

One Nation, Indivisible 415

Ward Connerly

Index 425

==============================

PART FOUR — EDUCATION

Desegregation and Resegregation in the Public

Schools

DAVID

J. ARMOR and CHRISTINE H. ROSSELL

When

the Supreme Court declared the end of official (de jure) segregation

in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, the public schools became

the center stage for the struggle to promote racial integration and equity in

America. Most of us born by the beginning of World War II will never forget the

graphic images of black children in Little Rock, Arkansas, being escorted into

school buildings by soldiers, surrounded by crowds of jeering white adults.

About a decade later, we saw similar crowds of white adults shouting epithets,

throwing stones, and burning buses when school desegregation moved to the North

in such cities as Pontiac, Michigan, and Boston, Massachusetts. Unlike other

social policies, vehement public protests did little to deter the school desegregation

movement because it was being advanced and enforced by the (almost) politically

immune federal courts.

From

the mid-1960s to the late 1970s a vast transformation took place in American

public schools as federal courts and government agencies demanded

race-conscious policies in every facet of school operations. The most

controversial aspect of school desegregation during this period involved the

rules for assigning students to schools, when racial balance quotas were

adopted instead of neighborhood or other geographic rules. In larger school

districts these racial quotas required mandatory busing, whereby students were

transported long distances from their former school to different schools across

a city or county in order to attain racial balance.

But

school desegregation court orders went far beyond student assignment, with

requirements for racial quotas in hiring, racial balance in the assignment of

faculty and staff, and racial equity in facilities (resources), transportation,

and extracurricular activities. These six desegregation plan components—student

assignment, faculty, staff, facilities, transportation, and extracurricular

activities—became known as the Green factors.

All school systems under court order had to show they had complied with each of

them before they could be declared unitary (nondiscriminating) systems and

released from court orders.1

There

has been much debate about whether school desegregation should be judged a

success or a failure, not just in the attainment of school racial balance but

also with respect to other social and educational goals such as improved race

relations and academic performance of minority children. So far as racial

balance is concerned, initially the most important objective of desegregation

plans, there is general agreement that substantial improvement occurred during

the early 1970s. But some critics, especially Gary Orfield and his colleagues

on the Harvard Project on School Desegregation, have asserted that

resegregation began occurring in the late 1980s and worsened in the early

1990s, particularly as federal courts began declaring school districts unitary

and ending court supervision.2

Although

early Supreme Court school decisions did not address social and educational

outcomes, there is little question that educators and civil rights activists

viewed racial balance as merely a means to an end. According to these views,

the ultimate goal of school desegregation was to reduce racial prejudice and

improve the academic achievement of African American children; schools were to

be the pathway to full economic and social parity with whites.

Assessing

the extent to which school desegregation has achieved these broader goals,

sometimes called extra-Green factors by the courts, is much more

complicated than assessing compliance with the six Green factors.

In particular, we have to assess a myriad of social and educational effects of desegregation,

and to be complete we have to compare these effects with the costs of

desegregation—monetary expenditures, political controversy, white “flight,” and

loss of local control. It is by no means obvious to the average citizen that

school integration, and especially the more intrusive practice of mandatory

busing, has any benefits at all, much less benefits that justify the costs.

Indeed, many Americans believe that mandatory reassignment or “forced busing”

has reduced the quality of education in school districts where it has been

implemented.3

This

essay will summarize the successes and failures of school desegregation with

regard to these issues. First, we assess the impact of desegregation policies

on actual racial balance in the public schools. The evidence indicates that

school desegregation has created substantial racial balance in our public

education systems. Second, we address the issue of resegregation to determine

whether the racial balance established in the 1970s by school desegregation

plans has been reversed by the unitary status findings of the 1980s and 1990s.

We shall show that at least as late as 1995 racial balance trends are not

reversing and that the changes in racial and ethnic isolation discussed by

Orfield are in fact caused by long-term demographic trends of declining white

and increasing minority enrollment, not the dismantling of desegregation plans.

Indeed,

as James Coleman first found, the mandatory reassignment plans of the 1970s

exacerbated these long-term demographic trends by accelerating the decline in

white enrollment, thereby limiting the extent of actual integration in the

school districts in which they were implemented.4 This effect was greatest in our

largest school districts. Finally, we evaluate evidence on the social and

educational effects of desegregation, and especially academic achievement. We

argue that in this area more than any other, school desegregation has failed to

deliver on its promises, in spite of the early optimism of many social

scientists and civil rights activists.

Racial

Balance

Prior

to Brown, most public schools in the South were onerace schools,

either white or black. Ten years after Brown, one study estimated that 99

percent of black children in the South were in one-race schools. The first

nationwide study of school segregation was ordered by the Civil Rights Act of

1964 and carried out by James Coleman and his colleagues during the 1965–66

school year.5 The Coleman report estimated that nationally 65

percent of all black students attended schools that were over 90 percent black,

while 80 percent of all white students attended schools that were over 90 percent

white.

PRE-SWANN

PROGRESS

The

extent of racial isolation in the South was far greater than in the North,

mainly because of de jure segregation in the South. Table 1 shows the

percentage of elementary black and white students in schools over 90 percent

black or white, respectively, for twenty-two of the largest Southern school

districts in 1965 or 1968. Although it is fair to say that some racial integration

had taken place in these Southern cities ten years after Brown, it

was clearly nominal for black students, with the notable exceptions of Kansas

City, Nashville, and Dallas. Indeed, it was precisely this token progress that

led to the Green decision, which called for the elimination of segregated

schools “root and branch.”6

Table

1 Percentage of Black and White Elementary Students in Schools over 90 Percent

Black or White, Southern Cities in 1965–1966 (except as noted)

|

School district |

Blacks in black schools |

Whites in white schools |

|

Birmingham,

Ala.a |

99 |

99 |

|

Mobile,

Ala. |

100 |

100 |

|

Little

Rock, Ark. |

96 |

97 |

|

Miami-Dade,

Fla. |

91 |

95 |

|

Jacksonville-Duval,

Fla.a |

92 |

92 |

|

Tampa-Hillsboro,

Fla.a |

91 |

91 |

|

Atlanta,

Ga. |

97 |

95 |

|

East

Baton Rouge Parish, La.a |

95 |

95 |

|

New

Orleans Parish, La. |

96 |

84 |

|

Kansas

City, Mo. |

69 |

65 |

|

St.

Louis, Mo. |

91 |

66 |

|

Jackson,

Miss.a |

99 |

100 |

|

Charlotte-Mecklenberg,

N.C. |

96 |

95 |

|

Oklahoma

City, Okla. |

90 |

96 |

|

Tulsa,

Okla. |

91 |

99 |

|

Charleston

County, S.C.a |

99 |

99 |

|

Memphis,

Tenn. |

95 |

94 |

|

Nashville,

Tenn. |

82 |

91 |

|

Dallas,

Tex. |

83 |

90 |

|

Houston, Tex. |

93 |

97 |

|

Norfolk, Va.a |

90 |

90 |

|

Richmond, Va. |

98 |

95 |

Source:

U.S.

Commission on Civil Rights, Racial Isolation in the Public Schools (Washington,

D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1967), pp. 4–5, except as noted.

a Computed by the

authors from the 1968 Office for Civil Rights enrollment data.

Racial

imbalance also existed in Northern cities during the mid-1960s, but racial

isolation was not nearly so extensive. Most Northern school segregation at that

time was thought to be de facto, that is, brought about by the private

decisions of citizens to live in different geographic areas. The highest levels

of racial isolation existed in Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Indianapolis,

Milwaukee, and Philadelphia where the black population swelled from

post–WorldWar II migration of Southern blacks looking for jobs in the large urban

centers of the North. This migration overwhelmed the capacity of white

neighborhoods to absorb blacks and still remain integrated, although none but

Chicago approached school racial isolation rates of 90 percent. Other large

cities with sizable, but in some cases smaller, black enrollments such as

Boston, Cincinnati, Columbus (Ohio), Los Angeles, Newark, New York, and San

Francisco had no more than half of their black students in predominately black

schools.

POST-SWANN

PROGRESS

The

situation in the South changed dramatically in the 1970s. In the 1971 Swann decision

for Charlotte-Mecklenburg, North Carolina, the Supreme Court endorsed strict

racial balance quotas for all schools in a system and approved cross-district

mandatory busing to attain complete racial balance.7 In

effect, the Supreme Court abandoned geographic school assignment (i.e., being

assigned to the closest school) for Southern school systems unless it resulted

in racially balanced schools, which was impossible in most larger school districts

because of segregated housing patterns.

Court-ordered

school desegregation moved to the North only two years later with the Supreme

Court’s Keyes decision for Denver, Colorado.8 We

shall not go into the complicated legal basis for Northern desegregation orders,

almost none of which involved state-enforced segregation. Suffice it to say

that despite de facto segregation in the North, systemwide racial balance

remedies and mandatory busing plans were ordered for many Northern districts

after Keyes. In addition, the Department of Health, Education,

and Welfare (HEW) was active in pressuring school systems to implement

desegregation plans, and several school systems adopted mandatory reassignment

plans under this pressure.

As a

result of local civil rights pressure, many other school systems adopted

voluntary transfer plans that involved M to M (majority to minority) transfers

where any student could transfer from a school in which his or her race was in

a majority to a school in which his or her race was in a minority. Another

common local initiative was to close some predominantly minority schools and

reassign the students to predominantly white schools; this was carried out in

such cities as Riverside, California, and Evanston, Illinois. Although these local

measures did not involve mandatory busing of whites, they nonetheless

accomplished some degree of school integration.

Table

2 Prevalence of Formal School Desegregation Plans, 1990

|

Size

of district |

Percent

with past or present desegregation plans |

Percentage

share of black/Hispanic students |

Total

districts in sample |

|

Very

large (N>27,000) |

72 |

53 |

145 |

|

Large

(N>10,000>27,000) |

39 |

22 |

421 |

|

Medium

(N>5,000>10,000) |

34 |

13 |

770 |

|

Small

(N>5,000) |

11 |

12 |

4,012 |

Source:

David

J. Armor, Forced Justice: School Desegregation and the Law (New York:

Oxford University Press, 1995), table 4.1.

The

first reliable data for assessing the impact of school desegregation on racial

balance was collected in 1968 by the Office for Civil Rights in HEW (OCR).9 The

survey consisted of enrollment data by individual schools and by five

racial-ethnic categories (white, black, Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian)

in a sample of school districts. There was no survey in 1969, but from 1970

through 1974 OCR collected data annually. Beginning in 1974, the survey was

conducted every other year and included all districts with court-ordered

desegregation plans. The sampling scheme used by OCR varied from year to year,

and thus after 1974 the OCR data do not constitute a representative sample of school

districts. In fact, in some years important school districts are simply

missing.

In

1990 the authors participated in a national survey of school desegregation and

magnet schools sponsored by the U.S. Department of Education, for which a

statistically representative sample of 600 school districts was drawn. The

original sample included all 150 largest school districts in the country, those

with enrollments over 27,000 students, and smaller percentages of the large,

medium, and small districts in the U.S., selected randomly from their size

category.10 In this essay we use this national sample to assess

racial balance trends, relying on OCR enrollment data from Fall 1968 through

Fall 1987 and Common Core of Data (CCD) enrollments from Fall 1989 through Fall

1995.

The

1990 survey gathered information about whether school districts had adopted

formal desegregation plans and what kinds of desegregation techniques were

used. Table 2 shows the percentage of school districts that had past or current

desegregation plans by size of district. The survey estimated from this random

sample that nationally nearly 1,000 school districts had some type of formal

desegregation plan, and the prevalence of formal plans increased with the size

of the school district. Of the 145 “very large” school districts that responded

to the survey, 102—more than 70 percent—had a formal desegregation plan at some

point in time. We note that the largest districts enroll about half of all

black and Hispanic students, while the smallest districts enroll only about

one-tenth of these minority groups. Thus, black and Hispanic students are more

likely to be found in larger districts, which are also more likely to have

school desegregation plans.

Of the

28 percent of very large districts that did not adopt a formal desegregation

plan, most were predominately white districts in the early 1970s, and indeed

many remained predominately white until at least the early 1990s. Examples

include Anoka County, Minnesota; Fairfax County, Virginia; Gwinnett County,

Florida; and Spokane,Washington. These districts were over 90 percent white in

1972 and remained over 70 percent white until at least 1991. Obviously, there

is less need for a formal desegregation plan when there are few minority

students.

How

effective have these plans been in achieving racial balance? To answer this

question, we shall use an index that summarizes the degree of racial balance in

a school system. Racial balance is defined as the degree to which each school’s

racial composition matches the districtwide racial composition for a given

race. The index of racial imbalance, also called the dissimilarity index,

ranges from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates total segregation (all schools are one

race), and 0 means perfect racial balance (every school has exactly the same

racial composition as the total district).11 Intermediate values represent the

proportion of students of one race who would have to be reassigned, if no

students of another race were reassigned, in order to attain perfect racial

balance.12 The index can be computed for any two racial or

ethnic groups; for example, whites and nonwhites, blacks and whites, or

Hispanics and whites.

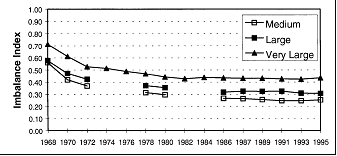

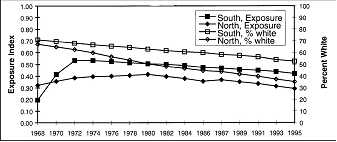

Fig.

1. Trends in black-white school imbalance in medium, large, and very large

districts.

BLACK

TRENDS

Figure

1 shows the trends in black-white racial imbalance from 1968 to 1995, separated

by size of school district.13 All three size categories show significant declines

in black-white imbalance (or increased desegregation), with the sharpest drops

from 1968 to 1972 corresponding to the widespread implementation of

desegregation plans in the South. For very large districts, racial imbalance

continues to decline until 1982 and remains stable thereafter; there is a

slight upturn of just 1 point between 1991 and 1995.

Medium-sized

districts show slight improvements in racial balance until 1991. For the nation

as a whole, then, contrary to Orfield’s claims, there is no evidence of

significant resegregation in terms of increasing racial imbalance as late as 1995.

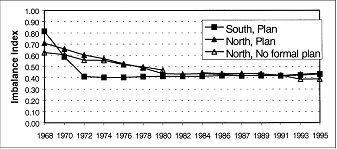

Fig.

2. Trends in black-white imbalance by plan status, very large districts.

There

was, however, substantial variation by region in the timing and scope of

desegregation plans, with Southern districts being the first to desegregate

with comprehensive desegregation plans involving white reassignments. After Swann, most

Southern districts that still had substantial racial imbalance were immediately

back in court and typically ordered to adopt busing remedies along the lines of

the Charlotte-Mecklenburg plan. As a result, comprehensive mandatory

desegregation plans were in place for most Southern districts by 1972.

Northern

mandatory busing remedies did not become commonplace until after the 1973 Keyes decision

in Denver, Colorado. Therefore, implementation of comprehensive desegregation

plans in the North tended to be distributed more evenly throughout the 1970s.

In addition, while most Southern districts had to adopt formal desegregation

plans, there were fewer formal plans in Northern districts primarily because

there was no history of de jure segregation and ongoing litigation associated

with dismantling it. Thus, fewer lawsuits were filed in the North, and

occasionally a lawsuit was dismissed because the courts found only de facto

segregation (e.g., Cincinnati). These different histories, not surprisingly,

produced different patterns of racial balance trends.

Figure

2 shows the trends in black-white racial balance for very large districts—those

that have received most of the attention by the courts and by school

desegregation analysts—separated according to region and formal plan status. We

do not show the small number of Southern districts that said they did not have

formal plans.14 The trends confirm the differences in desegregation

timing in the North and South. As expected, the most dramatic improvements in

racial balance occurred for Southern districts as they rapidly implemented

mandatory reassignment plans in the early 1970s. For Southern districts with

plans, the index of racial imbalance dropped by 40 points in the four years

1968–1972, from an average of 0.81 to an average of 0.41.

The

fact that the average index for Southern school districts was 0.81 in 1968

means that the dismantling of the de jure system of segregation had started

before 1968; had it not, the index would have been 1.0. Freedom-of-choice plans

became popular following enactment of the U.S. Civil Rights Act of 1964, and

they were the primary means of desegregation for many Southern school systems

until the policy was ruled insufficient by the U.S. Supreme Court in the Green decision.

Freedom-of-choice plans increased the number of black students attending former

white schools, but not vice versa, and they are the major reason that the index

was 0.80 in 1968 rather than 1.0.

The

pattern for Northern school systems with plans is quite different from that of

Southern systems with plans, in that the decline in imbalance is less rapid and

is spread evenly throughout the 1970s. The index dropped 36 points during the

decade, from 0.70 in 1968 to 0.44 in 1980, making them nearly as balanced as

Southern districts. Interestingly, Northern districts without formal plans also

experienced desegregation during this period, with the imbalance index

declining from 0.62 to 0.47. This trend is explained by the fact that many

school systems adopted desegregation practices during this time, such as

closing older imbalanced schools, building new schools in easier-to-integrate

locations, and paying closer attention to attendance zone changes, but did not

adopt a formal plan.

After

1980, racial balance trends level off for Southern districts but continue to

improve slightly for Northern districts, and in 1991 all three groups show the

same degree of racial imbalance (0.42). Most important, none of the categories

of school districts shows any dramatic worsening of racial balance between 1991

and 1995, with gains of only 1 or 2 points in the imbalance index for Southern

and Northern districts with plans, respectively. Once again, these data from

the largest 145 school systems in the nation contradict Orfield’s argument that

school districts are resegregating as a result of the dismantling of

desegregation plans.

HISPANIC

TRENDS

In

recent years the Orfield reports have expressed concern about the increasing

segregation and isolation of Hispanic students. This problem did not exist in

the era of de jure segregation because most early court decisions in the South

did not identify Hispanic students as a minority group that was a victim of

discrimination. Indeed, most Southern school districts classified students as

black and nonblack, and Hispanic students were included in the nonblack

category along with white students.

After

the 1973 Keyes decision in Denver, however, where both black and

Hispanic students were found to be victims of discrimination, it became commonplace

to treat all minority (nonwhite) students as a group in student assignments to

achieve racial balance. Interestingly, in a few school districts, such as

Yonkers, New York, the federal court found that only black and Hispanic

students were victims of discrimination, thereby combining Asian students with

white students for the purposes of desegregation. The court agreed with

plaintiffs’ argument that Asian students were not a disadvantaged minority

group, and therefore the Asian minority could be used to desegregate either

black or Hispanic minority students! This same definition is being used in a

recent desegregation plan in Rockford, Illinois. In the vast majority of school

districts, however, Asians are classified as racial minorities and assigned

accordingly.

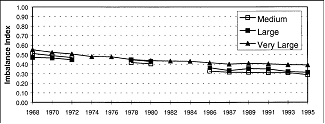

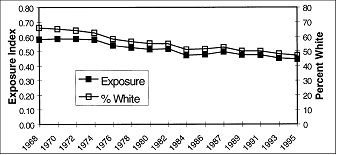

Fig.

3. Trends in Hispanic-white school imbalance.

Figure

3 shows the racial balance trends for Hispanic enrollment in relation to white

enrollment.15 Before 1970, Hispanics were clearly much less

segregated than black students in all size categories, which may explain in

part why Hispanics were not treated as victims of discrimination in early court

decisions. In 1968 the index is only 0.55 for Hispanics in very large districts,

compared with a value of 0.71 for black students. In large school districts the

Hispanic-white imbalance is 10 points less than the blackwhite imbalance. The

lower imbalance rates are explained by the greater residential integration of

Hispanics and whites during the 1960s, which is due in part to their smaller

population size.

After

1972, Hispanic-white imbalance declined steadily until trends begin to level

off in 1987, although there are still small declines as late as 1995. In very

large districts, where most black and Hispanic students are found, Hispanic

imbalance is less than black imbalance during the entire time period, and by

1995 Hispanic imbalance had fallen to 0.39, compared with 0.43 for blacks. In

large districts Hispanic students were more imbalanced than blacks between 1972

and 1980 but caught up with them by 1995. Hispanic imbalance has remained

somewhat higher in medium-sized districts during the 1990s, but we note that

index levels of about 0.30 reflect a relatively high degree of balance overall.

That is, an index of 0.30 means that in a district with half Hispanic and half

white students only 15 percent of Hispanics and 15 percent of whites would have

to be reassigned to attain perfect balance.

These

data show quite clearly that Hispanic-white imbalance has not been increasing

from the mid-1980s to the present time; in fact, it has continued to decrease

slightly during the 1990s and remains lower than black imbalance in very large

districts. Thus, contrary to the claims of Orfield, in our national

representative sample of school systems there is no evidence of increasing

segregation of Hispanic students in terms of racial imbalance, the primary

yardstick over the last four and a half decades for measuring the success of

desegregation plans.

Segregation,

Desegregation, and Resegregation

Having

said that there is no evidence of resegregation in terms of racial balance, we

must acknowledge that there are different ways of looking at this issue and

different ways of defining these terms. The original legal meaning of

segregation, as defined by the Supreme Court in 1954 in Brown, was

the separation of the races by official state action (de jure segregation). At

that time, desegregation was simply the abolition of state laws

and government practices that enforced these laws. But the elimination of state

laws requiring the separation of the races did not change segregated residential

patterns, nor did it prevent a variety of other strategies adopted by some

Southern states and school districts for avoiding meaningful integration.

The

Supreme Court decision in Green (1968) put Southern school districts

on notice that they must not merely stop discriminating but also must actually

achieve desegregated schools. It was not until the Swann decision

(1971), however, that a desegregated school was defined as one whose racial

composition is roughly the same as the racial composition of the entire school

system; that is, desegregation equals racial balance. This definition quickly

became the standard throughout the nation for a desegregated school system,

although the amount that a school could deviate from perfect balance varied

from case to case.

Using

this racial balance definition, there is no evidence of significant resegregation

in our nationally representative sample of American public school systems. But

the problem with a racial balance standard is that it ignores the total number

or proportion of white students in a school system. A racial balance standard

cares only that each school mirrors the school district’s racial composition,

not what the actual racial composition might be. A school system that is 90

percent black and 10 percent white would be perfectly balanced if every school

had 10 percent white enrollment. Yet such a school system would not be

considered desegregated by most interested parties. Many courts have defined a

90 percent black school as racially isolated, regardless of the systemwide

composition.

Moreover,

a desegregation plan can cause white flight and thus be the cause of a school

system’s being only 10 percent white. If a district starts out with a student

enrollment that is half black and half white but becomes only 10 percent white

several years later, most observers would not call the plan successful even if

each school was highly balanced at or near 10 percent. Thus, a racial balance

standard by itself gives us only a partial view of the amount of school

desegregation that exists in a school system.

In

order to overcome the limitation of racial balance definitions, James S.

Coleman created a second definition of desegregation that takes into account

the absolute proportion of white students in schools attended by black students

(or any other minority group).16 This definition is measured by a second summary

statistic called the index of interracial exposure— that is, the percentage of

white in the average black (or minority) child’s school.17 In

this case a value of 0 means total black-white segregation, or no whites in

schools attended by black students. The maximum value of this index is the

proportion of students who are white in the school system. If every school’s

percentage of white exactly matches the school system’s percentage of white,

the index will be the same as the proportion (or percentage) of white in the school

system.

For

example, if a system is 30 percent white, then an index of 0.30 would mean that

every school was 30 percent white (and therefore perfectly balanced), and an

index of 0.25 would indicate substantial degree of desegregation relative to

the available whites. But in absolute terms an index of 0.25 means that the

average school is 75 percent black, which indicates a relatively low level of

desegregation in absolute terms. Thus, the interracial exposure index reflects

both the extent of racial balance in the school system and the absolute level

of contact, that is, the percentage of white in the average black (or minority)

child’s school. When the exposure index is examined over time and is compared

with the percentage of white in a system, one can obtain a more comprehensive

picture of both the relative and absolute levels of desegregation.

Orfield’s

studies have used recent declines in the exposure index, rather than the

imbalance index, to argue that resegregation is occurring, a phenomenon he

attributes to the dismantling of desegregation plans. But there are two major

causes for a declining exposure index, one of which is simply a decrease in the

percentage of white in a school system. The decline in the percentage of white

enrollment can be due to nondesegregation-related demographic changes that have

nothing to do with racial balance, such as high black or Hispanic in-migration,

declining white birthrates, or normal middle-class white suburbanization. It

can also be caused by “white flight,” where whites leave a school system to

avoid mandatory busing. The other major cause of a declining exposure index,

the one that concerns Orfield, is a reduction in the number of racially

balanced schools, as might occur when a school district dismantles a

desegregation plan and returns to neighborhood schools.

If the

exposure index has been changing, is it due to declines in the percentage of

white or is it due to the dismantling of desegregation plans? This question can

only be answered by comparing the exposure index to trends in racial imbalance

and also to trends in the percentage of white. We have already demonstrated in

Figures 1–3 that racial imbalance has not changed significantly; it remains to

examine trends in the exposure index and in the percentage of white.

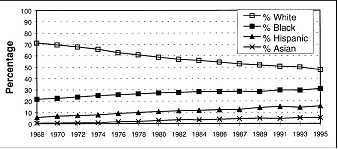

Fig.

4. Trends in racial composition, very large districts.

Figure

4 shows the national trends in racial composition for very large school

systems, including the average percentage of white that is the maximum for the

exposure index. In 1968 very large public school districts averaged 71 percent

white, 22 percent black, 6 percent Hispanic, and 1 percent Asian. For the next

twenty-five years the percentage of white declined steadily, while the

percentage of black, Hispanic, and Asian rose correspondingly, and by 1995 the

percentage of white enrollment had fallen to only 48 percent—less than half for

the first time. The decline in the percentage of white was somewhat steeper

during the mid-1970s, undoubtedly influenced by white flight from

desegregation. In the meantime, the percentage of black, Hispanic, and Asian in

the public schools increased to 31, 16, and 5, respectively, as a result of

demographic forces, including both in-migration and birthrates. Any

interpretation of trends in school desegregation indexes, in particular trends

in interracial exposure, must take into account these basic demographic

patterns because they limit the amount of interracial exposure that can be

achieved.

Fig.

5. Black-white exposure in very large districts with formal desegregation plans.

Figure

5 shows why the declining percentage of white cannot be ignored in an analysis

of interracial exposure. It shows the trends in black-white exposure by region

for very large districts with formal desegregation plans, juxtaposed with the

trend for percent of white enrollment. For Southern districts, the largest

changes in interracial exposure (solid squares) occurred between 1968 and 1972,

when the index rose from 0.20 to 0.53, an improvement of 33 points in the

average percentage of white students in schools attended by blacks. After 1972,

however, the index began a long, steady decline, falling to 0.42 by 1995. This

reduction in the absolute exposure index is not caused by increases in racial

imbalance, which remained nearly flat for the next twenty years (see Fig. 2),

but rather the steady decline in the percentage of white enrollment (open

squares), which dropped from 68 percent in 1972 to 53 percent in 1995. In fact,

the exposure index for Southern districts fell at a slower rate than the

percentage of white, indicating that interracial exposure was actually

increasing slightly relative to the available white enrollment. The exposure

index is 15 points from its maximum in 1972 (68 minus 53), and it is only 11 points

from its maximum in 1995 (53 minus 42).

A

similar pattern exists for very large Northern districts with plans. As was the

case with racial balance, the exposure index (solid diamonds) increased over a

longer period, improving from 0.32 in 1968 to 0.41 in 1980, a gain of 9 points

in the average percentage of white in schools attended by blacks. The index

does not even reach 0.50, however, before it begins a long, inexorable decline

over the next fifteen years, falling to only 0.29 by 1995. As in the South,

this decline is the result not of increasing racial imbalance, which is nearly

flat during this time, but rather of a steeply falling percentage of white

enrollment: this fell from 50 in 1980 to only 35 in 1995. Again, relative to

the available whites, interracial exposure actually improves slightly; it is 9

percentage points from its maximum in 1980 and is only 6 points from its

maximum in 1995.

Fig.

6. Hispanic-white exposure for very large districts.

Finally,

Figure 6 shows the trends in the exposure index and the percentage of white for

Hispanic students in very large districts with Hispanic enrollment greater than

1 percent.18 As Orfield has noted, the exposure of Hispanics to

white students has declined substantially from its high in 1972 (0.59) to its

low in 1995 (0.45). But the decline is not due to increasing imbalance, because

Figure 3 shows that Hispanic-white imbalance declined during this time for very

large districts. Again, the decline is caused by the declining percent of white

enrollment in these districts, which has fallen from 64 in 1972 to only 47 in

1995. Relative to the available whites, then, Hispanic-white exposure has

actually increased, and in 1995 it is only 2 points from its maximum value. In

other words, Hispanic students in very large districts are actually more

desegregated than black students, both in absolute terms and relative to the

available white enrollment.

By

comparing the trends in racial composition with the trends in racial balance

and interracial exposure, a much clearer picture emerges about how and why

desegregation levels have changed in recent years. For the fifteen-year period

between 1980 and 1995 (1972–1995 for Hispanics), three patterns emerge: the

percentage of white has declined, racial balance has remained relatively

constant, and interracial exposure has declined. Thus, the cause of declining

interracial exposure is the overall decline in the percentage of white, rather

than the dismantling of desegregation plans.

It may

be appropriate to say that resegregation is occurring for both black and

Hispanic students, in that they find themselves attending schools with a

dwindling number of white students, particularly in larger Northern districts.

But we must be clear about the cause of that resegregation: if ending

desegregation plans were a significant factor, we would see significant increases

in racial imbalance. Because this is not happening, and because the percentage

of white enrollment is decreasing,we must conclude that the resegregation is

due primarily to demographic change in the form of falling white enrollments

and increasing minority enrollments.

Social

and Educational Results

The

existence of long-term national school enrollment data by race makes it a good

deal easier to determine the effect of school desegregation plans on school

racial balance and interracial exposure than to determine their effect on

social and academic outcomes. Although there is a great amount of data on

academic achievement, either from national efforts like the National Assessment

of Educational Progress (NAEP) or from local school districts that administer

standardized achievement tests, it is very difficult to sort out the impact of

desegregation from the effects of many other factors that influence academic

achievement, especially family socioeconomic characteristics, because there are

so few data on these other factors. This has led to substantial disagreement

among researchers about the academic effects of desegregation.

It is

even more difficult to assess the effect of school desegregation on social and

psychological outcomes such as race relations, racial prejudice, and

self-esteem because we lack standardized measures for these variables. Consequently,

with the exception of opinion polls on racial issues, there are few national

data on social outcomes, and there is no way to relate that data to

desegregated schools. Accordingly, we must rely on case studies carried out in

individual school districts to assess the effect of desegregation on such

outcomes as student interracial attitudes and behaviors. Fortunately, there are

reviews of this research literature that are helpful.

ACADEMIC

ACHIEVEMENT

The

debate over desegregation and achievement has continued unabated since the

early 1970s, when the first evidence appeared that desegregation was not

improving black achievement.19 In spite of the claims and expectations of many

supporters of desegregation during the 1960s, and in spite of the existence of

comprehensive and well-funded desegregation plans in many school districts

throughout the nation, there is not a single example in the published

literature of a comprehensive racial balance plan that has improved black

achievement or that has reduced the black-white achievement gap significantly.

Significantly,

the most recent social science study of school desegregation— Orfield and Eaton’s

attack on the courts for “dismantling desegregation”— cited only a single

comprehensive desegregation plan that has led to significant minority

achievement gains or a reduction of the achievement gap.20 Indeed,

out of seven major desegregation plans analyzed as case studies in this book,

the authors did not even discuss minority achievement in three widely discussed

cases—Charlotte-Mecklenburg, Detroit, and Little Rock.

Further,

they were largely skeptical of local school staff reports claiming significant

achievement gains in three other case studies—Kansas City, Missouri, and two

Maryland counties, Montgomery and Prince Georges— but they did not conduct any

original analyses to support their argument. Finally, the only case they cite

where desegregation allegedly improved black achievement was Norfolk, Virginia,

where the data they used were from a study by David Armor that concluded just

the opposite!21 We shall remedy these omissions by presenting new

and independent analysis of achievement results for Charlotte, Kansas City, and

Prince Georges County.

There

are a number of major reviews of the research literature on this question, and

though they do not agree precisely on what the research says, a general picture

does emerge. If there is any effect of desegregation on academic achievement,

it is highly variable (sometimes it occurs and sometimes it does not), the

effects are modest at best, and positive effects occur for reading but not for

math. These are the conclusions of three major reviews of research, including

one by Nancy St. John in 1975, one by Thomas Cook et al. in 1984, and one by

Janet Schofield in 1994.22

The

Cook review, synthesizing the separate reviews of a panel of six experts

convened by the National Institute of Education, captured the essence of this

equivocal state of affairs: “On the average, desegregation did not cause an

increase in achievement in mathematics. Desegregation increased [black] mean

reading levels . . . between two and six weeks. . . . Little confidence should

be placed in any of the mean results presented earlier . . . [because] I find

the variability in effect sizes more striking and less well understood than any

measure of central tendency.”23

Moreover,

we now have massive amounts of national achievement data from the NAEP project,

which also includes information on student background and school

characteristics.How do the NAEP data inform us about the performance of

minority students in desegregated versus segregated schools? What have we

learned about the academic achievement of minority students who have spent most

of their education in desegregated schools? Interestingly, officialNAEPreports

do not address these important questions. Indeed, it is remarkable, given all

the national data, the controversy, and local experience, that there are few

published studies that have tried to answer these questions using NAEP or case

study data.

At the

outset of this discussion, it is important to distinguish two different types

of processes that would cause desegregation plans to have an effect on

achievement. The first, and the one assumed by most studies of desegregation

and achievement, is that the major causal mechanism is the change in the racial

composition of schools; that is, by the improved racial balance that occurs

with desegregation. Under this causal assumption, racial isolation is harmful

because it deprives minority students of contact with more middle-class and

(usually) higher-achieving white students, who help set the pace of study and

the standards of achievement. Racial isolation might also lead to a

concentration of less effective teachers in minority schools, if more effective

teachers gravitate to more integrated or predominately white schools.

The

second possible causal mechanism by which school desegregation might have an

effect on achievement is when a school board makes significant changes in the

types and distribution of programs and resources among schools as part of the

desegregation plan. These effects might be most pronounced during the early

years of desegregation, if a district maintained inferior programs and

resources in predominantly black schools at the time of desegregation (a

circumstance not generally found by the 1965 Coleman study of equal

opportunity).24 In this case improvement in minority achievement

should take place regardless of racial balance.

A

corollary to this second effect is a condition where desegregation improves

programs and resources for all schools, in which case we might see improvement

for all students regardless of race or racial balance. If the first effect is

true, minority achievement should be higher or the gap narrower whenever racial

composition improves, regardless of programs and resources, and there should be

no achievement gains for segregated minority students or for white students. If

the second effect is true, minority achievement could improve in desegregated

or segregated schools, and white achievement might also improve. Of course,

factors other than desegregation and program changes can improve academic

achievement; the leading nonschool factor would be improved socioeconomic

status. The impact of socioeconomic status on academic achievement is well

documented in social science research, and therefore this possibility must be considered

whenever achievement differences or achievement gains are studied.

NAEP

STUDIES

The

NAEP program has documented a significant improvement in black achievement (but

not white achievement) and therefore a closing of the achievement gap between

1970 and 1990. In 1970 the gap in reading was just over one standard deviation

for three different age groups, and by 1990 it had declined to between 0.7 and

0.8 standard deviations.25 Similar patterns were observed for math

achievement. Because this improvement corresponds to a period of extensive

desegregation, some have suggested that desegregation was the primary cause.

In

1998 a Rand team carried out one of the few studies to use NAEP data to examine

the possible effect of desegregation on black achievement gains. They concluded

that desegregation might explain part of the improvement. 26 Unfortunately,

their complicated methodology utilized aggregate data on several regions of the

country, and they did not analyze achievement trends for black students who

actually attended segregated or desegregated schools. Therefore, from their

methodology it is impossible to determine whether potential effects are due to

improved racial balance or to changes in programs that affected all minority

students, regardless of their racial balance status.

The

only published study to date that compares NAEP achievement trends for black

students according to school racial composition found that black achievement

gains were approximately the same in majority nonwhite and majority white

schools.27 Although this finding could reflect program

improvements due to desegregation and implemented in all schools, the study

suggested that improvement in parents’ education (as documented in the NAEP

data) was a major contributor.

A more

direct way to determine the relationship between academic achievement and

desegregation is to show how students are performing on NAEP tests according to

their school racial composition. Because students who attend predominately

white schools are more likely to have higher socioeconomic (SES) levels than

those who attend predominately minority schools, such as higher parent

education, more two-parent families, and more educational materials at home, we

have to adjust the test scores of students to take these SES characteristics

into account. This is done using a statistical technique (multiple regression)

that removes the effect of SES on student achievement.28 This

statistical analysis enables us to adjust students’ test scores for SES and in

that way to make clear comparisons of students of the same social class in

schools of varying racial composition.

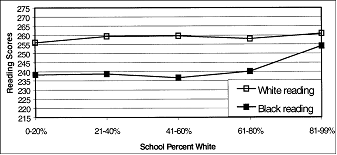

Fig.

7. School percent white and reading achievement, 1992 NAEP, age 13, adjusted

for individual SES.

Figure

7 shows the results of an original analysis of the national reading scores for

thirteen-year-olds in 1992, adjusted for individual SES characteristics. Across

the first four categories of racial composition, ranging from predominately

black to 80 percent white, there are no significant differences or trends in

black achievement or in the black-white gap. These schools enroll more than 97

percent of the national black sample. There is a significant improvement for a

small group of black students in predominately white schools (only 45 out of

1,329 in the black sample), most of whom are in 90 percent–plus white schools.

Even assuming this is a reliable result, it is not likely due to racial

composition itself, given the lack of a trend in the other categories; more

likely, it is a self-selection effect or an effect of unmeasured family

characteristics that cannot be evaluated.

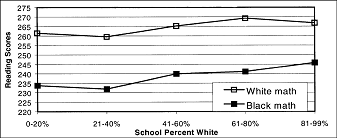

Fig.

8. School percent white and math achievement, 1992 NAEP, age 13, adjusted for

individual SES.

Figure

8 shows an analysis of math achievement for the same group of students. The

pattern here is quite different; both black and white students score higher in

schools that are over 40 percent white, and therefore the achievement gap

remains relatively constant across the first four categories of school (it

narrows significantly only for the small group of black students who are in

highly white schools). Because the improvement occurs for both groups, it is

probably not due to racial balance; rather, it is more likely to be due to

programmatic differences among the schools or unmeasured SES factors. Whatever

the cause, attending a racially integrated school does not reduce the math

achievement gap between black and white students in this national sample.

Similar

results were obtained for the seventeen-year-old age groups as well as for

Hispanic students. Therefore, the NAEP data do not support the thesis that

desegregated schools significantly benefit black or Hispanic reading

achievement, nor do they reduce the black-white or Hispanicwhite achievement

gap in mathematics.

CASE

STUDIES

The

NAEP data have the advantage of being national in scope, but they have some

serious drawbacks as well. For example, the NAEP data do not include

information on the existence, scope, or duration of desegregation plans within

a district. Although the data include the racial composition of the student’s

school, they do not explain why the racial composition exists or how long it

has been that way. For this reason it is useful to look at a number of case

studies of the effects of comprehensive desegregation plans on achievement.

Several

recently published case studies include Pasadena, California; Norfolk,

Virginia; and Charleston, South Carolina.29 In 1970, three years before the Keyes decision,

Pasadena became one of the first Northern school districts to implement a

districtwide racial balance plan, having been ordered to do so by a federal

district court. From 1970 to 1973 there was no improvement in the reading

scores of a first-grade cohort of black students in fully desegregated schools.

Norfolk,

Virginia, was fully desegregated and racially balanced by 1970. Fourth-grade

test scores were available from 1965 to 1982. Both black and white test scores

actually fell dramatically after desegregation. The blackwhite gap narrowed

somewhat between 1970 and 1973 but only because white achievement fell more

than black achievement. Between 1973 and 1980 achievement scores improved for

both races, but they did not reach their predesegregation levels until 1978;

the gap remained constant during this time. A special compensatory program that

was initiated in 1978 may have produced the gains in 1979 and 1980. But in

1981, when a new test form was introduced, scores fell again. There was also

some evidence that improper coaching and teaching before the test may have

accounted for some of these increases. Even so, one can certainly conclude that

racial balance had no positive impact on black or white fourth-grade

achievement between 1970 and 1978.

Similar

results were found in Charleston, South Carolina, where the court-approved

desegregation plan did not produce racial balance in every school. Charleston

was a countywide district with subdistricts that governed student and teacher

assignment, hence racial balance was required only within subdistricts. The

case study compared reading achievement for black third- and fourth-graders in

schools with varying degrees of racial composition across subdistricts and

found no significant difference in test scores, or change in test scores, among

predominately black schools, predominately white schools, and racially balanced

schools.

Fig.

9. Trends in New Castle County, Delaware, 6th-grade reading.

Some

additional case studies (unpublished to date) are of special interest because

of the nature of their desegregation plans. Three of these case studies present

original data analyses from school districts discussed by Orfield and Eaton:

Kansas City, Missouri; Prince Georges County, Maryland; and

Charlotte-MecklenburgCounty,North Carolina. Another is from the Wilmington–New

Castle County district, which had a unique courtordered desegregation plan.

In

1978 a federal court ordered the merger of predominately black Wilmington,

Delaware, with ten predominately white New Castle County districts to form a

single metropolitan school district, and a countywide desegregation plan was

implemented. It is one of the few metropolitan consolidation and busing plans

to be ordered by a court and ultimately adopted. The case is of special

interest because, unlike many central city plans, black students attend most of

their school years in majority white suburban schools whose student bodies have

remained relatively middle class (in some cases, affluent) since the start of

the plan. As late as 1993 the New Castle County districts (the single district

was divided into four districts in 1981) were among the most racially balanced

districts in the country. Not only did the vast majority of schools range from

65 to 75 percent white, but also every school was at least majority white.

Figure

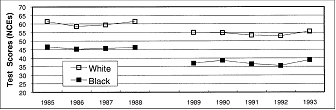

9 shows trends in sixth-grade reading scores for students in all four New

Castle County districts.30 In 1985, when sixth-graders would have attended

racially balanced schools since kindergarten, we see a black-white gap of 15

points, or about three-fourths of a national standard deviation. Moreover,

there is no improvement in black sixth-grade test scores, nor is there a

reduction in the achievement gap over the nine years shown. In 1993 the

black-white gap is 17 points (on a different test), or about eighttenths of a

standard deviation, similar to the 1992 achievement gaps for the NAEP reading

tests. In spite of these stable, desegregated, and majority white schools

located in middle-class neighborhoods, the presumed ideal environments for

raising black achievement, there are neither significant black gains nor

reductions in the black-white gap. Clearly, the Wilmington case does not

support the thesis that racial balance will reduce the achievement gap.

Fig. 10.

Trends in Kansas City, Missouri, 5th-grade achievement, ITBS composite scores.

Nor is

it a question of money. In 1986 a federal court ordered Kansas City, Missouri,

to implement what may well be the most expensive remedial plan in history.

Kansas City had been operating a desegregation plan since the late 1970s. But

in 1986 the court ordered an expanded plan involving extensive construction,

renovation, and the addition of magnet programs to most of the elementary and

all the secondary schools, whose purpose was to attract suburban whites into

this 70 percent minority school system. With a unique court-ordered tax levy

and court-ordered funding from the state, total school expenditures reached

$10,000 per pupil by 1990, with total funding exceeding $1.5 billion over

approximately an eight-year period. Unfortunately, not enough white students

came to the city from the suburbs to lower the minority percentage

significantly.

As the

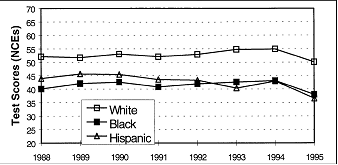

achievement trends in Figure 10 reveal, this extraordinary degree of expenditures

for one of the largest magnet programs in the nation apparently did nothing to

raise the achievement levels of black students, which remained substantially

below white achievement from 1988 to 1995. In fact, when a new test form was

implemented in 1995, scores of all students fell significantly, raising the

possibility that some coaching or teaching of test content may have taken place

during preceding years. Although the black-white achievement gap is somewhat

narrower than in Wilmington or in the NAEP, this appears to be due to low white

scores rather than to high black scores (Kansas City has a relatively high

proportion of white students in the free lunch program). Thus, spending an extraordinary

amount of money on a school desegregation plan and on magnet schools does not

seem to improve minority achievement significantly or decrease the

minority-white achievement gap.

Fig.

11. Prince Georges County, Maryland, black test scores by school type, 1996,

grade 3.

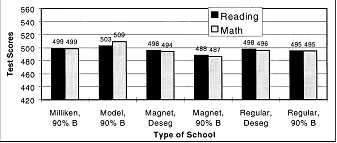

The

Prince Georges County case is noteworthy because of a different approach taken

in its second school desegregation plan. A predominantly white suburban county

outsideWashington, D.C., Prince Georges adopted a comprehensive pairing and

busing plan in 1973. This was followed by extensive white flight and black

in-migrationfrom the District of Columbia, and the county schools became

majority black in the early 1980s. Recognizing that not all schools could

achieve meaningful racial balance, a modified desegregation plan was adopted in

1985 that provided for several types of schools: desegregated magnet schools,

desegregated regular schools, and “Milliken II” schools, which were

predominantly black and received additional resources and funding. Later, as

white enrollment losses continued, some of the magnet schools and some of the

regular schools became predominately black; they also added a category of “Model”

schools, which were predominately black and received extra resources but not as

much as Milliken schools.

These

different types of programs and desegregation levels offer a unique opportunity

to sort out the potential effects of racial balance from the effects of special

compensatory programs and extra funding. Figure 11 shows third-grade test

scores (from a Maryland statewide test) for black students in six types of

schools, after adjusting scores for student background characteristics. Though

the scores vary somewhat across the different types of schools, there is no

apparent benefit from attending a desegregated school, most of which are

approximately half black and half white. After controlling for SES and initial

ability, black students attending desegregated magnet and desegregated regular

schools score no higher than black students at predominately black regular

schools (which average around 90 percent black), and they score somewhat lower

than black students in the enriched but predominately black Milliken and Model schools

(which exceed 90 percent black). It is not clear why black students score

lowest at the predominately black magnet schools and highest at the predominately

black Model schools, but whatever the reason it is not because of their racial

composition, which is identical.

Fig.

12. Achievement trends in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, North Carolina, grades 3 and

6.

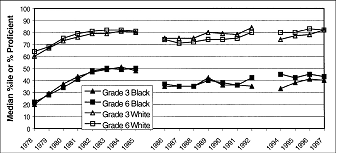

The final

case study to be presented is Charlotte-Mecklenburg, North Carolina, which is

especially important historically because of the famous U.S. Supreme Court

decision in this case. The Swann decision upheld a lower court order

to adopt a comprehensive, countywide mandatory busing program to attain racial

balance in all schools, thereby creating a standard for desegregation that was

applied throughout the nation for many years. Because Charlotte was a large

county district with a relatively low black enrollment in 1970, it was able to

sustain very extensive racial balance for the next twenty years while at the

same time preserving a majority white school system. It has been described in

the Orfield and Eaton book as one of the most successful desegregation plans in

the country, with unprecedented local support from educators, civil rights

leaders, and the business community.

Figure

12 shows the long-term achievement trends for third and sixth graders from 1978

to 1997. In 1978 black elementary students had been in well-desegregated

schools from kindergarten on, yet they scored only at the 20th percentile in

both reading and math compared with national norms. Test scores began

increasing dramatically for both black and white students, reaching maximums in

about 1983, when black students scored at the national norm of 50. The reason

for the increase is not clear, but it is not likely due to desegregation, which

had been in place for eight years before 1978. Some of the increases may have

been due to coaching or teaching test content because scores for both races

dropped significantly when a new test form was adopted in 1986. Though the

black-white gap had diminished somewhat by 1983, it returned to its original

magnitude in 1986 (about one standard deviation) and remained relatively

constant until the last CAT test was administered in 1992. A sizable test score

gap also existed between 1994 and 1997, but it cannot be compared directly with

the CAT gap because it comes from a different statewide test that uses a different

metric. Thus, one of the most successful desegregation plans in the country did

not reduce the black-white achievement gap significantly.

These

case studies bolster the NAEP results shown in Figures 7 and 8, that racial

composition by itself has little effect on raising the achievement of minority

students or on reducing the minority-white achievement gap. Some studies show

that there is no relationship at all between black achievement and racial

composition (controlling for student SES), and other studies show that there is

no relationship between the black-white achievement gap and racial composition.

In either case, though there is some evidence here that achievement can be

affected by programmatic changes, there is no evidence that it responds to

improved racial balance by itself.

RACE

RELATIONS AND ATTITUDES

Studies

of the effect of desegregation on racial attitudes and race relations were

fairly common during the 1970s, when the desegregation movement was at its

peak. There seems to be less interest in these issues now, perhaps because the

early studies offered little support for the notion that desegregation would

bolster self-esteem, lower racial prejudice, and improve race relations.

The

first major review of the effect of desegregation on race relations and

attitudes was by St. John, whose study was published in 1975.31 She evaluated

35 studies conducted between 1966 and 1973 of changes in white attitudes or

behaviors after desegregation. She found 11 studies in which white prejudice

worsened, 11 where it improved, and 13 where there was no change or mixed

results. She also evaluated 28 studies of changes in black prejudice after

desegregation, finding 10 where black prejudice worsened, 6 where it improved,

and 12 where there was no change or results were mixed. Her review also

evaluated the effect of desegregation on the self-esteem of black children, one

of the key concerns of the Supreme Court in Brown. Out

of 35 studies, she found 14 where black self-esteem was higher in segregated

than desegregated schools, 5 where it was higher in desegregated schools, and

16 where there was no significant difference.

Walter

G. Stephan conducted a similar type of review about ten years later.32 Although

he reviewed a smaller number of studies, his 28 studies covered a longer time

span (1963–1981) and included only those with a reasonably sound methodology.

His findings were remarkably similar to those of St. John. Out of 24 studies of

change in white attitudes or behavior, he found 11 where desegregation

increased white prejudice, 4 where it decreased, and 9 where there was no

change. Of the 17 studies of black attitudes and behaviors, he found 5 showing

that desegregation worsened black prejudice, 4 where it improved, and 8 where

there was no difference. In his review of black self-esteem in 28 studies, he

found 7 where desegregation lowered black self-esteem, 1 where it was improved,

and 19 where there was no change. It is interesting that the majority of

studies during this period found that black self-esteem was generally higher

than white self-esteem, thus calling into question the Supreme Court’s

psychological harm thesis.33

The

evidence on the benefit of school desegregation for race relations is probably

the weakest of all. Indeed, there are more studies showing harmful effects than

studies showing positive effects. This led to another and more recent reviewer

of the race relations literature to conclude, somewhat generously: “In general,

the reviews of desegregation and intergroup relations were unable to come to

any conclusion about what the probable effects of desegregation were. . . .

Virtually all of the reviewers determined that few, if any, firm conclusions

about the impact of desegregation on intergroup relations could be drawn.”34

The

reluctance of reviewers to draw conclusions about the benefits of school

desegregation for race relations or self-esteem only reinforces our conclusion

that the psychological harm theory of de facto segregation and the social

benefit theory of desegregation are clearly wrong, at least when applied to

desegregation as a racial balance policy. Of course, the original psychological

harm theory presumed official segregation sanctioned by laws, which was pretty

much gone by the mid-1960s and before the time when most of the studies above

were conducted. But supporters of the harm and benefit thesis have applied it

far more broadly, to cover any type of racial imbalance or racial disparity

arising from any cause, and even today it forms the ideological basis for desegregation

and affirmative action policies. It is this broader formulation that fails

under scrutiny of the research evidence.

Conclusions

What

can we say about the success and failures of the school desegregation movement?

If we evaluate school desegregation policy within the constitutional framework

established by the Supreme Court on the matter of race in Brown,

which is much narrower than the goals of many civil rights advocates, there are

indeed successes. The failures come, for the most part, from attempts to extend

this original framework to see school desegregation as a means of resolving a

whole host of racial issues never contemplated by Brown.

First,

we must not diminish the fact that Brown forever

changed the fundamental way in which America deals with race, not only in

schools but also throughout society. In particular, it forbade all official

actions that segregated students or staff by race, or that sanctioned

discriminatory distribution of resources, facilities, and activities. Second,

after the Court allowed consideration of race in fashioning desegregation

plans, what followed was an unprecedented change in the way students and staff

were assigned to schools, eventually creating extensive racial balance in

schools to an extent never attained in any other sector of society.

That

racial balance has largely continued to the present time, with or without court

orders. Although the Supreme Court has returned to its original conception of

race, permitting school systems to be declared “unitary,” after which race

cannot be used for student assignment (whether for racial balance or

imbalance), there has been no rush to dismantle desegregation plans and return

to strict neighborhood school policies. The reason is that racial balance and

racial diversity have become desired goals, especially within the educational

establishment. True, a number of unitary school systems, like Norfolk, Oklahoma

City, Cleveland, and Prince Georges County, now have some neighborhood schools,

but most of these districts have retained such politically palatable

desegregation policies as magnet programs, voluntary transfers, and minimal

integrative geographic zoning. Indeed, that is why the racial balance indexes

have remained so stable for the past fifteen years.

The

biggest threat to desegregation is not the dismantling of plans but rather the