Report: Racism

New Perspectives on Race and

Ethnicity

Part 1

The Demography of Racial and Ethnic Groups

Immigration and Group Relations

What Americans Think About Race and

Ethnicity

PART TWO — PRIVATE LIVES AND PUBLIC POLICIES

Residential Segregation Trends

African American Marriage Patterns

Discrimination, Economics, and Culture

Half Full or Half Empty? The Changing

Economic Status of African Americans, 1967–1996

Discrimination in Public Contracting

==============================

Hoover Institution

http://www-hoover.stanford.edu/publications/books/colorline.html

Beyond the Color Line: New

Perspectives on Race and Ethnicity in America

Edited by Abigail Thernstrom

and Stephan Thernstrom

Hoover Institution Press Publication No. 479

2002

==============================

Abstract

From color-blind to color-consciousness—a counterproductive approach to racial equality?

The American racial and ethnic landscape has been radically transformed over the past three decades. A generation ago, blacks had much less education, much poorer jobs and were more likely to live in solidly black neighborhoods than they are today. Yet the old notion of “two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal” still persists thirty years after it first appeared in the misguided diagnosis of the Kerner Commission report.

America’s changing racial and ethnic scene is the central theme of Beyond the Color Line. In essays covering a range of areas including education, law, religion, immigration, family structure, crime, economics, politics, and more, this volume examines where we’ve been, where we are, and where we’re going. Along the way, the authors attempt to illuminate how we have moved from Dr. Martin Luther King’s dream of all Americans being judged solely by the “content of their character, not the color of their skin” to today’s vaguely Orwellian civil rights orthodoxy—that it is necessary to treat some persons differently in order to treat them “equally.”

The product of the Citizens’ Initiative on Race and Ethnicity—formed in 1998 as an alternative to the one-sided official “dialogue” on questions of color—many of these twenty-five brief essays offer either explicit or implicit public policy recommendations. A common theme unites them—new realities require new thinking, and old civil rights strategies will not solve today’s problems. Beyond the Color Line takes the first steps toward a new civil rights agenda.

Abigail Thernstrom, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a member of the Massachusetts State Board of Education since 1995, and Stephan Thernstrom, the Winthrop Professor of History at Harvard University and Manhattan Institute senior fellow, are coauthors of America in Black and White: One Nation Indivisible (Simon & Schuster, 1997) and write frequently for a variety of journals and newspapers, including The New Republic, the Wall Street Journal, and the UCLA Law Review.

Contributors: David J. Armor, Michael Barone, Douglas J. Besharov, Clint Bolick, David Brady, Linda Chavez, William A.V. Clark, Ward Connerly, John J. DiIulio Jr., Tamar Jacoby, Everett C. Ladd, George La Noue, William J. Lawrence, Nelson Lund, Christine H. Rossell, Sally Satel, Thomas Sowell, Shelby Steele, Abigail Thernstrom, Stephan Thernstrom, Martin Trow, Reed Ueda, Eugene Volokh, Finis Welch, James Q. Wilson, C. Robert Zelnick

==============================

Table Of Contents

Foreword ix

John Raisian and Larry Mone

Contributors xi

Introduction 1

PART ONE THE BIG PICTURE

The Demography of Racial and Ethnic Groups 13

Stephan Thernstrom

copyright © 2001 by Stephan Thernstrom

Immigration and Group Relations 37

Reed Ueda

What Americans Think About Race and Ethnicity 53

Everett C. Ladd

Wrestling with Stigma 69

Shelby Steele

PART TWO PRIVATE LIVES AND PUBLIC POLICIES

Residential Segregation Trends 83

William A. V. Clark

African American Marriage Patterns 95

Douglas J. Besharov and Andrew West

Crime 115

James Q. Wilson

Health and Medical Care 127

Sally Satel

Supporting Black Churches 153

John J. DiIulio Jr.

PART THREE ECONOMICS

Discrimination, Economics, and Culture 167

Thomas Sowell

copyright © 2001 by Thomas Sowell

Half Full or Half Empty? The Changing Economic Status of African Americans, 1967–1996 181

Finis Welch

Discrimination in Public Contracting 201

George R. La Noue

PART FOUR EDUCATION

Desegregation and Resegregation in the Public Schools 219

David J. Armor and Christine H. Rossell

The Racial Gap in Academic Achievement 259

Abigail Thernstrom

copyright © 2001 by Abigail Thernstrom

Schools That Work for Minority Students 277

Clint Bolick

Preferential Admissions in Higher Education 293

Martin Trow

PART FIVE LAW

Racial and Ethnic Classifications in American Law 309

Eugene Volokh

copyright © 2001 by Eugene Volokh

Illusions of Antidiscrimination Law 319

Nelson Lund

PART SIX POLITICS

Race, Ethnicity, and Politics in American History 343

Michael Barone

The Politics of Racial Preferences 359

David Brady

From Protest to Politics: Still an Issue for Black Leadership 369

Tamar Jacoby

PART SEVEN ONE NATION, INDIVISIBLE

The New Politics of Hispanic Assimilation 383

Linda Chavez

In Defense of Indian Rights 391

William J. Lawrence

The Battle for Color-Blind Public Policy 405

C. Robert Zelnick

One Nation, Indivisible 415

Ward Connerly

Index 425

==============================

Foreword

Projects

with multiple authors scattered across the country are often arduous and

unfulfilling. To the contrary, this project was neither. There is a reason we

engaged in this effort; we wanted to put together, into one volume, the best

work being conducted by the highest-quality scholars addressing race and

ethnicity issues facing the citizens of the United States. The opportunity for

our two institutions to collaborate with experts in the area of race and ethnic

relations to produce this book was one we could not pass on; the results proved

to be rewarding.

The

exemplary work of the twenty-five scholars and writers that constitute Beyond the Color

Line has made this volume comprehensive and influential.We

thank each of them for their time, patience, and outstanding scholarship. In

addition, we are especially grateful to the editors, Abigail and Stephan

Thernstrom, for their dedication in undertaking and completing this project.

Based

on accumulated knowledge, intellectual rigor, reasoned argument, and sound

principles, the Hoover Institution and the Manhattan Institute are dedicated to

producing and disseminating sound research with public policy implications.

John

Raisian, Director, Hoover Institution

Lawrence

J. Mone, President, Manhattan Institute

==============================

Contributors

David

J. Armor is a research professor at the Institute of Public

Policy, George Mason University. Formerly he was Senior Social Scientist at the

Rand Corporation and Associate Professor of Sociology at Harvard University. He

is the author of Forced Justice: School Desegregation and the Law, and

he has testified as an expert in more than thirty school desegregation cases.

Michael

Barone is a columnist at U.S. News&World Report. The

author of Our Country: The Shaping of America from Roosevelt to Reagan (Free Press,

1992), Mr. Barone regularly appears as an analyst and commentator on various

television and radio news shows. He is a graduate of Harvard College and Yale

Law School.

Douglas

J. Besharov is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute

and director of the AEI’s Social and Individual Responsibility Project. He is

also a professor at the University of Maryland School of Public Affairs. He is

the author of the forthcoming America’s Families: Trends,

Explanations and Choices, and of many other books and articles that have

appeared in major magazines and newspapers across the country. Andrew West was

a research assistant at AEI.

Clint

Bolick serves as vice president and director of litigation

at the Institute for Justice, which he co-founded in 1991 to engage in

constitutional litigation protecting individual liberty and challenging the

regulatory welfare state. He leads the nationwide litigation effort to defend

school choice programs and to challenge regulatory barriers to

entrepreneurship. The New York Times described Mr. Bolick as “the maestro of the

political right on issues of race . . . increasingly setting the tone and

defining the terms of the national debate.”

David

Brady is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution.He is

also Bowen H. and Janice Arthur McCoy Professor of Political Science and

Leadership Values in the Stanford Graduate School of Business and associate

dean and professor of political science in the School of the Humanities and

Sciences at Stanford University. His recent publications include Revolving

Gridlock: Politics and Policy from Carter to Clinton (Westview

Press, 1998).

Linda

Chavez is president of the Center for Equal Opportunity, a

Washington, D.C.–based think tank devoted to the promotion of color-blind equal

opportunity and racial harmony. She has held a number of political positions,

among them White House Director of Public Liaison and director of the U.S.

Commission on Civil Rights. She is the author of Out of the Barrio:

Toward a New Politics of Hispanic Assimilation (Basic

Books, 1992) and is currently working on her second book.

William

A. V. Clark is a professor of geography at the University of California,

Los Angeles. His research is focused on the internal changes in U.S. cities,

especially in the changes that occur in response to residential mobility and

migration. He is author of The California Cauldron: Immigration and the

Fortunes of Local Communities (Guilford Press, 1998) and Households and

Housing: Choice and Outcomes in the Housing Market (Rutgers,

1996).

Ward

Connerly is chairman of the American Civil Rights Institute,

a national not-for-profit organization aimed at educating the public about the

problems created by racial and gender preferences. A member of the University

of California Board of Regents, Mr. Connerly spearheaded the successful fight

to end the University’s use of race as a factor in admissions. He has since led

campaigns against racial preferences in Florida and Texas. john

j. diiulio jr. is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. He directs

the Jeremiah Project, an initiative of the Manhattan Institute’s Center for

Civic Innovation. He is also Frederick Fox Leadership Professor at the

University of Pennsylvania and senior counsel to Public/Private Ventures.

Tamar

Jacoby is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, who

writes extensively on race issues and other subjects. She is the author of Someone Else’s

House: America’s Unfinished Struggle for Integration (Free

Press, 1998), a book about race relations in three American cities—New York,

Atlanta, and Detroit. Ms. Jacoby’s articles and book reviews have been

published in a variety of periodicals, including the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal,

Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, the New Republic,

New York Review of Books, Commentary, Dissent, City Journal, and Times Literary Supplement.

Everett

C. Ladd, who died in 1999, was director of the Institute

for Social Inquiry at the University of Connecticut and executive director and

president of the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research. He was also an adjunct

scholar of the American Enterprise Institute, as well as a columnist for the Christian

Science Monitor from 1987 through 1995. Dr. Ladd was the author of

seventeen books, most recently The Ladd Report on Civic America (Free

Press, 1999).

George

R. La Noue is a professor of political science in the Policy

Sciences Graduate Program at the Univeristy of Maryland Baltimore County. He is

also director of the Project on Civil Rights and Public Contracts at the University.

Dr. La Noue’s Ph.D. was granted by Yale University.

William

J. Lawrence is publisher of the Native American

Press/Ojibwe News, an independent weekly newspaper that serves

Minnesota’s Native American community. In 1997, Press/ON was

nominated for a Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing and service to the

community. The April 1999 issue of Minnesota Monthly featured

an article about Mr. Lawrence entitled “The Man Tribal Leaders Love to Hate.”

Dr. Lawrence holds a B.A. from Bemidji State University and a J.D. from the

University of North Dakota School of Law. He was a commissioned officer in the

U.S. Marine Corps serving in Vietnam, and he is an enrolled member of the Red

Lake Band of Chippewa Indians.

Nelson

Lund is a professor at the School of Law, George Mason

University. Before joining the faculty in 1992, he was associate counsel to

President George Bush. Mr. Lund has served in the Office of Legal Counsel and

the Office of the Solicitor General of the U.S. Department of Justice and as a law

clerk to Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and to U.S Court of Appeals Judge Patrick

E. Higginbotham.

Christine

H. Rossell is a professor of political science at Boston

University. Ms. Rossell is the author of four books and many scholarly articles

in the areas of school desegregation and bilingual education policy. She has been

an expert witness in more than twenty school desegregation and bilingual

education cases and has helped design and defend more than a half dozen

voluntary “incentive” desegregation plans.

Sally

Satel is a practicing psychiatrist and lecturer at Yale

University School of Medicine. She is staff psychiatrist at the Oasis Clinic in

Washington, D.C. In addition to publishing widely in medical journals and the popular

press, Dr. Satel is the author of PCMD: How Political Correctness Is

Corrupting Medicine (Basic Books, 2000).

Thomas

Sowell is the Rose and Milton Friedman Senior Fellow on

Public Policy at the Hoover Institution. He is the author of a nationally

syndicated column that appears in over 150 newspapers. Dr. Sowell has written

widely on economics, the history of ideas, and social policy. His most recent

book is The Quest for Cosmic Justice (Free Press, 1999).

Shelby

Steele is a research fellow at the Hoover Institution. Mr.

Steele’s most recent book isA Dream Deferred: The Second Betrayal of Black

Freedom in America (Harper Collins, 1998). He is also author of The Content of

Our Character: A New Vision of Race in America (HarperCollins,

1990), which won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1990.

Abigail

Thernstrom is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and coauthor

of America in Black and White: One Nation, Indivisible (Simon

& Schuster, 1997). Her previous book, Whose Votes Count: Affirmative Action

and Minority Voting Rights (Harvard University Press, 1987), won four academic

prizes. She has been a member of the Massachusetts State Board of Education

since 1995 and writes frequently for a variety of journals and newspapers,

including New Republic, Commentary, theWall Street Journal, the New York Times, and Public Interest.

Stephan

Thernstrom is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and Winthrop

Professor of History at Harvard University, where he teaches American social

history. His most recent book, coauthored with Abigail Thernstrom, is America in Black

and White: One Nation Indivisible (Simon & Schuster, 1997). He is

also the editor of the Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (Harvard

University Press, 1980).

Martin

Trow is emeritus professor at the Goldman School of

Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley.He holds a degree as a

mechanical engineer from Stevens Institute of Technology and a doctorate in

sociology from Columbia University. He has written widely on the sociology of politics

and higher education. He is a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of

Sciences and was recently awarded the Berkeley Citation for distinguised

service to the University of California.

Reed

Ueda is a professor of history at Tufts University and

on the steering group of the Committee on Migration at the Center for

International Studies of MIT.He is author of Postwar Immigrant America:ASocial

History (Bedford Books of St. Martin’s Press, 1994), among

other books and articles. Dr. Ueda was also research editor for Harvard

Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (Harvard University Press, 1980).

Eugene

Volokh is a professor at the University of California, Los

Angeles, School of Law. Before he joined the faculty at UCLA, he clerked for

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and for U.S. Court of Appeals Judge Alex Kozinski. Mr.

Volokh teaches free speech law, copyright law, the law of government and

religion, and a seminar on firearms regulation law and policy.

Finis

Welch is a professor of economics and George T. and

Gladys H. Abell Professor of Liberal Arts at Texas A&M University. His

specialty is in labor economics, on which he has written many articles and

papers. Dr. Welch did his doctoral research at the University of Chicago.

James

Q. Wilson taught political science at Harvard University from

1961 to 1987, where he was the Shattuck Professor of Government. From 1985 until

1997 he was the James Collins Professor of Management and Public Policy at

UCLA. He is the author or coauthor of fourteen books, the most recent of which

is Moral Judgment (Basic Books, 1997). In addition, he has edited or

contributed to books on urban problems, government regulation of business, and

the prevention of delinquency among children.

C.

Robert Zelnick, a professor of journalism at Boston University,

spent twenty-one years with ABC News, including reporting assignments in Moscow

and Israel, at the Pentagon, and covering Congress and politics. A former

Hoover Institution visiting fellow, he is the author of Gore: A Political

Life (National Book Network, 1999) and Backfire:A Reporter’s

Look at Affirmative Action (Regnery, 1996).

==============================

Introduction

The

American racial and ethnic landscape has been fundamentally transformed

in recent decades. But public understanding has lagged behind new realities. Our

gaze is often fixed on the rearview mirror, and even that view is distorted. A

color line seems to bifurcate the nation. Blacks appear as permanent victims;

white racism looks ubiquitous. Asian and Hispanic Americans, who together now

outnumber blacks, are but a shadowy presence hovering in the background. Their

experience as “people of color” is portrayed as little different from that of

African Americans.

White

racism, of course, was ubiquitous not that long ago. And it has not entirely

disappeared. But the past is not the present. We have been moving forward. Much

of the territory that now surrounds us is unfamiliar, and yet old notions

persist. The ethnic and racial categories themselves— white, black, Asian, and

Hispanic—never made much sense and are, in any case, dissolving. Half of

native-born Asian Americans are now marrying whites. A third of all Hispanics

marry non-Hispanic whites. The black intermarriage rate is slowly creeping up.

A generation ago blacks had much less education and much poorer jobs and were

much more likely to live in solidly black neighborhoods than they are today.

Differences persist, but they now have multiple and complex causes.

America’s

changing racial and ethnic scene is the central theme of this volume. In essays

on topics ranging from religion and immigration to family structure and crime,

the authors seek to illuminate where we have been, where we are, and where we

are heading. They share a common vision: the color line transcended. One

nation, indivisible is still America’s unrealized dream.

The

Color-Blind Vision

Pessimism

is strikingly pervasive in civil rights circles today. In the heyday of the

civil rights movement, by contrast, those who fought for racial equality were

optimists, and that optimism seemed vindicated by events. With the passage of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act a year later, the civil

rights movement achieved its main political objectives. As Bayard Rustin, a

close adviser to the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., noted at the time, the “legal

foundations of racism in America” had been “destroyed” with dizzying speed. The

“elaborate legal structure of segregation and discrimination” had “virtually

collapsed.”1 Most Americans— not just those directly involved in

the movement—celebrated.

Indeed,

the 1964 election returns were a smashing victory for civil rights proponents.

Barry Goldwater, the Republican candidate for president who opposed the Civil

Rights Act, was resoundingly rejected. Democrats gained an additional thirty-seven

seats in the House and one more in the Senate, giving them majorities of more

than two-thirds in both chambers. It was a partisan imbalance the like of which

has not been seen since.

It is

no coincidence that in 1965 the United States also abandoned the discriminatory

national origins quotas that had governed its immigration law since the 1920s.

The notion that only citizens from countries like Great Britain or Germany

would make good Americans lost popular support in the increasingly tolerant and

cosmopolitan America of the postwar period. Congress amended the Immigration

and Nationality Act to open the doors to prospective immigrants from all

countries on an equal basis.

Immigration

reform and the two landmark civil rights bills—the most important since

Reconstruction—all rested on a central moral principle: it is wrong to judge

Americans on the basis of race, color, creed, sex, or national origin. People

are individuals with equal rights, not fungible members of groups. The

Constitution is “color-blind,” John Marshall Harlan had declared in his famous

dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 Supreme Court decision that upheld “separate

but equal” railroad accommodations.2 It was the message of the civil

rights movement from before the CivilWar to the 1960s.3 Dr.

King dreamed of the day when Americans would be judged solely by the “content

of their character,” not by “the color of their skin.”4 President

John F. Kennedy invoked this core principle in supporting the passage of a

sweeping civil rights bill that would demonstrate the nation’s commitment to “the

proposition that race has no place in American life or law.”5

The

Reversion to Color-Consciousness

The

clarity of this moral vision was lost, however, in the turbulent and chaotic

years of the late 1960s. In 1965 President Lyndon B. Johnson took the first

step in a radically different direction. “You do not take a person who, for

years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the

starting line in a race and then say, ‘you are free to compete with all the

others,’” Johnson argued. Opening “the gates of opportunity” would not suffice;

racial “equality as a fact and as a result” had to be the nation’s goal.6 Although

Johnson did not use the term “affirmative action,” his image of blacks as

crippled by racism laid the foundation for a generation of racial

preferences—race-conscious measures designed to ensure “equality as a fact.”

Handicapped citizens were entitled to compete under different rules.

The

rationale for the racial preferences that came to be embedded in policies

involving employment, education, and public contracting was most famously

articulated by Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun in 1978. “In order to get

beyond racism,” he said, “we must first take account of race. There is no other

way. And in order to treat some persons equally, we must treat them

differently. We cannot—we dare not—let the Equal Protection clause perpetuate

racial supremacy.”7 It was not clear why policies that were explicitly

race conscious were the only alternative to racial supremacy; in the

extraordinarily long debates on the 1964 Civil Rights Act, no one ever made

Justice Blackmun’s argument. The framers of that statute had envisioned

aggressive enforcement of its race-neutral antidiscrimination provisions. But

by 1978 the vaguely Orwellian notion that it was necessary to treat some

persons “differently” in order to treat them “equally” became civil rights

orthodoxy.

The

Misguided Diagnosis of the Kerner Report

How

did race-conscious policies become so accepted by 1978? The answer, in part, is

the racial crisis that erupted in the nation’s cities within three months of

Johnson’s June 1965 speech. In August, the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles

exploded in flames, kicking off four “long, hot summers” of looting, burning,

and fighting in predominantly black areas of cities across the land.

The

riots came to an end in 1968, as suddenly and mysteriously as they appeared,

and what caused them is still open to debate. But the explanation offered by

President Johnson’s Kerner Commission was a sweeping indictment of American

society. Indeed, the Commission’s central finding became, and remains,

conventional wisdom in the civil rights community, academia, and the national

media. The 1968 report portrayed America in stark—literally

black-and-white—terms. The American drama was a play with only two characters:

bigoted whites and victimized blacks. Whites were mostly living in suburban

comfort, while blacks were trapped by white prejudice in decaying, dead-end

inner-city neighborhoods. Curiously, the report barely mentioned the great

civil rights statutes that had already irrevocably changed the status of blacks

in both South and North. It portrayed the nation as moving backward, “toward

two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.” The riots were

natural and inevitable protests against “the racial attitudes and behavior of

white Americans toward black Americans.” An “explosive mixture” had accumulated

in the cities “since the end ofWorldWar II,” and it was not surprising that the

powder keg had at last detonated. America would be marked by “deepening racial

division” and “ultimately, the destruction of basic democratic values” until “white

racism” disappeared.8

As an

analysis of what had triggered the ghetto riots of the mid-1960s, the Kerner

report was useless. Increasing inequality could not have been the explanation;

by every conceivable measure the status of African Americans had improved.

Their average incomes were rising more rapidly than those of whites—no

surprise, given how far behind they had been. In years of schooling,

occupational status, quality of housing, and life expectancy, the racial gap

was narrowing significantly. The political power of blacks was expanding, and

they had an array of new legal rights.9

Of

course, African Americans were still more likely than whites to live in poverty

and suffered from higher unemployment rates, but those conditions were just as

pervasive in the cities that had not experienced riots. Moreover, the riots

ended in 1968. Why? Inner-city neighborhoods had not been transformed, white

racism had not suddenly disappeared, and in the few months that elapsed between

the Kerner report and the last racial disturbance, the federal government had

not begun the program of massive new spending that the Commission had

recommended.

Looking

Backward: Liberal Orthodoxy Today

In

spite of these and other glaring flaws, the portrait drawn by the Kerner

Commission has had a remarkable life. Its findings are frequently cited as

equally valid today. For instance, in December 1999 the attorney general of

Massachusetts looked at student scores on statewide tests and recalled the

Kerner Commission’s “pessimistic conclusion that our nation was ‘moving towards

two societies, one black, one white, separate and unequal.’”10 Although

the Kerner findings were barely mentioned explicitly, the report of the Race

Advisory Board appointed by President Clinton and chaired by Dr. John Hope

Franklin was a warmed-over version of the Kerner report with updated rhetoric.

Its findings were a prime example of what Orlando Patterson has called the “forever

racism” mindset. 11

New

demographics compelled the Franklin Commission to acknowledge the large and

rapidly growing presence of Asians and Hispanics, though it did so largely by

conflating the experience of all “people of color.” The United States, it said,

is still governed by an oppressive “system of racial hierarchy” in which whites

hold all the power and members of “every minority group” face “significant

barriers to opportunity.” “Racial and ethnic oppression . . . persist.” “Racial

stereotypes” and “racist concepts” abound, as ugly and primitive as ever; no

area of life is free of “subtle biases.”12

A

similarly gloomy and strident note was struck in a recent address by Julian

Bond, the chairman of theNAACP. Though he conceded that African Americans had

made some advances since the 1960s, he insisted that the Kerner Commission’s “indictment

of white America” was still sound. “Everywhere we look we see clear racial

fault lines that divide America now as much as in the past.” Within a few short

years of the Kerner report, a “backlash in the discourse over race” had set in,

Bond claimed. Its findings were rejected by “a curious mix of whites and a few

blacks, academics, journalists and policy makers,” engaged in “blame-shifting”

and determined to pervert reality. These “new racists,” he said, see continuing

blackwhite disparities as the consequence of “family breakdown,” a “lack of middle-class

values,” a paucity of “education and skills,” and the “absence of role models.”

But “these are symptoms. Racism is the cause; its elimination is the cure.”13

Looking

Forward

The

two dozen contributors to this volume disagree about many things; they were not

chosen because they follow a particular party line on racial and ethnic issues.

But they all reject the civil rights orthodoxy expressed by Julian Bond and the

Franklin Commission. The Kerner report was a highly imperfect guide to the

American picture when it was first released, and by now it is about as reliable

as a telephone directory issued thirty years ago. The ritualistic evocation of

a color line perpetuated by old and new racists is futile and

counterproductive.The drive for racial equality is unfinished business, yet the

civil rights community has almost nothing fresh to offer.

What

follows is a guide to the new territory shaped by seismic shifts in American

society over the past three decades. How are various groups faring

economically, both in absolute terms and in relation to each other? What are

the social conditions in the new communities of color? What progress have we

made in closing the gap in educational outcomes? How is the law changing? How

much has the sharp increase in marriages across racial lines blurred the

boundaries between groups and diminished the salience of racial

identifications? How are shifting attitudes—white, black, Asian, Hispanic,

American Indian—reflected in the nation’s politics? Are voters crossing racial

lines in casting ballots for candidates?

The

twenty-five brief essays offered here address these questions and more. The

authors are scholars, journalists, and activists who specialize in the areas

they write about. Grounded in research and close observation, almost every

chapter shatters an old stereotype.

Many

of the essays offer either explicit or implicit public policy recommendations. A

common theme unites them: new realities require new thinking—a new civil rights

agenda. It is undeniable that serious racerelated problems persist—most

obviously for black Americans. But the causes of those problems entail

complexities of which the Kerner Commission never dreamed. White racism does

not work as the simple explanation for the relatively poor academic performance

of most black students in contexts ranging from affuent suburbia to black-run

school districts. Too many black children live in poverty, but almost all are

in single-parent households; how can we encourage young women to postpone

pregnancy until they are married or well positioned to support a family? The

problems of poverty, inadequate education, high unemployment, among others,

appear unchanged, but the facade of continuity is deceptive, and old civil rights

strategies will not solve today’s problems.

This

collection is the work of the Citizens’ Initiative on Race and Ethnicity

(CIRE), formed in April 1998 as an alternative to what many Americans saw as

President Clinton’s one-sided “dialogue” on questions of color. The Hoover

Institution at Stanford University and the Manhattan Institute for Policy

Research generously supported the group’s work and the research and writing

that went into the essays. Lindsay Young, director of communications at the

Manhattan Institute, served as the project coordinator, and Richard Sousa of

the Hoover Institution guided the publication process. All thirteen CIRE

members contributed to the conception and planning of the volume.

Citizens’

Initiative On Race And Ethnicity

Clint

Bolick, Institute for Justice

Elaine L. Chao, Heritage Foundation

Linda Chavez, Center for Equal Opportunity

Ward Connerly, American Civil Rights Institute

Tamar Jacoby, Manhattan Institute

Barbara J. Ledeen, Independent Women’s Forum

Gerald A. Reynolds, Center for New Black Leadership

T. J. Rodgers, Cypress Semiconductor

Shelby Steele, Hoover Institution

Abigail Thernstrom, Manhattan Institute

Stephan Thernstrom, Manhattan Institute

Robert L. Woodson Sr., National Center for Neighborhood Enterprise

C. Robert Zelnick, Hoover Institution

Notes

1. Bayard

Rustin, “From Protest to Politics: The Future of the Civil Rights Movement,”

Commentary, February

1965, reprinted in Rustin, Down the Line: The Collected

Writings of

Bayard Rustin (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1971), p. 111.

2. 163 U.S. 537

(1896).

3. See Andrew

Kull, The Color-Blind Constitution (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard

University

Press, 1992).

4. Martin

Luther King Jr., “I Have a Dream,” speech, 1963 March onWashington.

Reprinted in

James MelvinWashington, ed.,ATestament of Hope: The EssentialWritings

of Martin Luther

King, Jr. (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1986), p. 219.

5. Radio and

Television Report to the American People on Civil Rights,” June 11,

1963, in Public Papers of

the Presidents of the United States: John F. Kennedy, Containing

the Public

Messages, Speeches, and Statements of the President, January 1 to November

22, 1963 (Washington,

D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1964), pp. 468–71.

6. Lyndon B.

Johnson, “To Fulfill These Rights,” address at Howard University,

June 4, 1965,

reprinted in Lee Rainwater and William L. Yancey, eds., The Moynihan

Report and the

Politics of Controversy (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1967), p. 126.

7. Regents of the

Univ. of Calif. v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 407 (1978).

8. National

Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders [Kerner Commission] Report

(New York:

Bantam, 1968), pp. 1, 2, 10.

9. The data on

black progress in this period are assembled in Stephan Thernstrom

and Abigail

Thernstrom, America in Black and White: One Nation, Indivisible (New

York: Simon

& Schuster, 1997), chaps. 3–6.

10. Thomas F.

Reilly, “Separate and Unequal Education,” Boston Globe, op-ed,

December 11,

1999, p. A19. For other claims that the Kerner Commission’s findings

were still

correct, see Fred R. Harris and RogerW. Wilkins, eds., Quiet Riots:

Race and

Poverty in the

United States: Twenty Years After the Kerner Report (New York:

Pantheon,

1988); Douglas

S. Massey and Nancy Denton, American Apartheid: Segregation and the

Making of the

Underclass (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1993),

p. 211;

and Charles

Bullard, J. Eugene Grigsby III, and Charles Lee, eds., Residential

Apartheid:

The American

Legacy (Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Afro-American

Studies, 1994),

pp. 1–2.

11. The

Patterson phrase is cited in Jim Sleeper, “Al Gore, Racial Moralist,” New

Republic, March 2,

1998, p. 21.

12. President’s

Initiative on Race Advisory Board, One America in the 21st Century:

Forging A New

Future (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office,

1998),

pp. 36, 43–44.

13. Julian

Bond, “Hostility to Civil Rights, ‘Color Line’ Problems to Continue,”

Charlestown

Gazette, April 1, 1999, p. 5A.

==============================

PART ONE — THE BIG PICTURE

The Demography of Racial and Ethnic Groups

STEPHAN

THERNSTROM

The

United States has been a racially and ethnically diverse society

from its beginnings. But the conventional wisdom these days is that something

radically new is happening now—that demographic changes are fundamentally

transforming our society in unprecedented ways. Peering into a crystal ball,

many observers have claimed that the groups we currently designate as

minorities are destined to become the new majority. By the middle of the

twenty-first century, they predict, and perhaps even sooner, whites will have

been reduced to minority status and “people of color” will have become the

majority. This, it is claimed, will have momentous implications for the nation’s

political, social, and cultural life.

Such

is the argument, for example, of Peter Brimelow’s Alien Nation, a 1995

volume that contended that current population shifts were “so huge and so

systematically different from anything that had gone before as to transform—and

ultimately, perhaps, even to destroy—the . . . American nation.”1

Table

1 Public Beliefs About the Racial Composition of the U.S. Population, 1995

What percent of

the population is . . .?

minority

|

Responses by |

Black |

Hispanic |

Asian |

Total |

|

Non-Hispanic

whites |

24 |

15 |

11 |

50 |

|

Blacks |

26 |

16 |

12 |

54 |

|

Hispanics |

23 |

21 |

11 |

55 |

|

Asians |

21 |

15 |

8 |

44 |

|

Actual

1995 figures |

13 |

10 |

4 |

27 |

source:

WashingtonPost–Kaiser

Family Foundation–Harvard University survey, as given in Richard

Morin, “A

Distorted Image of Minorities,” Washington Post, November 8,

1995, p. A1. Survey results

are mean

figures. The actual 1995 figures are Current Population Survey estimates

reported in U.S.

Bureau of the

Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1997 (Washington,

D.C.: U.S. Government

Printing

Office, 1997), table 12.

Brimelow

is a conservative, but many observers on the multicultural left are equally

convinced that a profound demographic transformation is under way. They are

cheered rather than dismayed by the prospect, however. They welcome the arrival

of a minority majority and see it as evidence of the need for immediate

action—for more multicultural education in the schools, continued affirmative

action and diversity training programs in higher education and the workplace,

and an expanded welfare state.

The

demographic projections upon which both sides of this debate depend are too

flawed to be taken seriously, as I shall argue later. But the general public

seems to have got the message—so it would appear, at least, from the results of

a 1995 poll that asked Americans to estimate what proportion of the population

belonged to various racial or ethnic groups (see Table 1). This survey revealed

that whites (that is, non-Hispanic whites, a distinction to be discussed at a

later point) thought that the black population was almost twice as large as it

was in fact—24 percent in their minds, just 13 percent in reality—and that

there were 50 percent more Hispanics and almost three times as many Asians in

the country as the Current Population Survey figures revealed there to be.

These three minority groups together, whites thought, made up fully half of the

total population, when they actually were little more than one quarter. The “minority

majority,” in the eyes of whites, was not a possibility in the remote future;

whites were already on the brink of losing their traditional majority status.2

It is

tempting to interpret this misconception as evidence of widespread white

paranoia. But the delusion was not confined to whites. Indeed, blacks and

Hispanics were even more prone than whites to exaggerate their numbers. They

also greatly exaggerated the size of other minority groups: minorities together,

they believed, were already a distinct majority of the population, constituting

54 or 55 percent of the total. Asians were a little better informed than other

groups, but they too greatly overestimated the size not only of their own group

but also of other minorities. Whatever their backgrounds, most Americans tended

to have similar misconceptions about the racial-ethnic composition of the

nation’s population.3

It has

long been claimed that nonwhite people are socially invisible in American

society and that the minority presence deserves to be given far more attention

than it receives on television, in the press, in classrooms and textbooks.

President Clinton’s Race Initiative was based on the premise that most white

Americans do not pay sufficient attention to their fellow countrymen with skins

of a different hue. These polling numbers suggest that the opposite may be

closer to the truth: Americans have become so attentive to racial divisions and

so obsessed with racial matters that they have developed a badly distorted

picture of the shape of their society.

The

Arbitrary and Unscientific Character of the Official Racial-Ethnic Categories

in Current Use

The

survey referred to above employed four crude categories: white, black,

Hispanic, and Asian. Why are these the relevant categories for subdividing the

population into cultural groups? Why are these few groups singled out for

attention, while a great many others with some claim to a distinct identity are

not? What about Italian Americans, for example, or Jews? Are divisions among “races”

deeper, more fundamental, and more enduring than divisions among “ethnic groups”?

The

idea that “race” is a crucial and immutable division of mankind is a product of

the primitive social science of the nineteenth century. According to theorists

of the day, all the peoples of the world were divided into four distinct races:

white or “Caucasian,” black or “Negroid,” yellow or “Oriental,” and red or

Indian. White, black, yellow, and red people were profoundly different from

each other, as different as robins from sparrows, trout from salmon, rabbits

from squirrels.People who belonged to different races were not only distinct

physical types; they differed in innate intellectual potential and in cultural

development. If they were to mate across racial lines, their offspring would be

biological monstrosities.

Since

these race theorists were white, it is hardly surprising that they fervently

believed that Caucasians were the superior race. Orientals were next in line,

with blacks and American Indians at the bottom of the heap. Given this premise,

it was only natural that representatives of the “most advanced” race believed

that they were entitled to rule over the “lesser breeds.”

Such

ideas have long been discredited and are now held only by those on the lunatic

fringe. Scientists today agree that the genetic differences that distinguish

members of supposedly different “races” are small, and that the races have

become so intermixed that few people can claim to be of racially “pure”

origins. The range of biological variation within any one race is far greater

than the average differences among races.

And

yet the government of the United States, remarkably, still utilizes these

antiquated and pernicious categories in compiling statistical information about

the American people. The entry on the black population in the index to the 1997

edition of the Statistical Abstract of the United States gives

230 citations to tables that distinguish African Americans from other Americans.

Another 140 citations direct the reader to data on “Hispanics,” a newly

invented quasi-racial category whose origins will be traced below. Asians and

Pacific Islanders get 42 references, and American Indians and Alaskan natives

47. If you want to know how many African Americans regularly use the Internet,

how many Asians were treated in hospital emergency rooms in the preceding year,

how many Hispanics usually eat breakfast, or how many American Indians were

arrested for burglary, the answers are all there. The federal government

inundates us with data that convey the unmistakable message that Americans of

different “races” differ from each other in many important ways.

It is

very striking that the American public is not bombarded with similar official

statistics on the socioeconomic characteristics of Catholics, Protestants,

Jews, and Muslims, and the many denominational subdivisions within those broad

categories. Why not? Religious groups in the United States differ, often quite

dramatically, in levels of education, income and wealth, SAT scores,

unemployment rates, and most other socioeconomic measures. Why shouldn’t the

public be able to find out if Jews are much wealthier than Presbyterians, on

the average, or if Mormons are more likely to attend college than Southern

Baptists? The government of the United States has never inquired into the

religious affiliations of individual citizens because religion is regarded as a

private matter in American society and not the business of government. If such

information did become readily available, the effect might be to heighten

tensions between people of different faiths, inspiring some to complain that

they did not have their “fair share” of federal judgeships or of seats on the

boards of large corporations and that others were “overrepresented” in those

positions.

If not

religion, why race? The racial categories currently used by the federal

government derive from discredited racial theories more than a century old,

with only minor changes in nomenclature. “Negroid” has given way to “black” or “African

American,” and “Oriental” has been replaced by “Asian.” But the idea that it is

meaningful and socially useful to cram us all into one of the four racial boxes

constructed by racist thinkers more than a hundred years ago remains unchanged.

The previous decennial census, in 1990, still accepted the traditional premise

that every American belongs in one and only one of four mutually exclusive

racial categories; people of racially mixed ancestry were required to record

just one race on the census forms. The Census of 2000 has broken from this

tradition and allowed respondents to give more than one answer to the race

question, but for purposes of civil rights enforcement the results will be

tabulated in the same old crude categories, rendering the change virtually

meaningless.4

The

issue is not confined to the U.S. Census. Nineteenth-century conceptions of

race are also alive and well in the official guidelines that govern the

statistical information that all federal agencies must gather. The

authoritative statement of current practice is the Office of Management and Budget’s

Directive No. 15, “Race and Ethnic Standards for Federal Statistics and

Administrative Reporting,” first issued in 1977 and still in effect.5 Directive

15 declared that the population of the United States was divided into four “races”

and two “ethnic” groups and required all agencies of the federal government to

compile data using these categories in order to assess the impact of their

programs.

The “racial”

groups identified in Directive 15 were the usual ones: whites, blacks, Asians

and Pacific Islanders, and American Indians and Alaskan Natives. Even though

the old idea of a racial hierarchy with whites on top had lost all intellectual

respectability, the guidelines set forth in Directive 15 were designed to

subvert that hierarchy. The rationale for requiring all governmental agencies

to subdivide the population into these particular racial categories was that

these nonwhite groups had been the targets of prejudice in the past. (So had

many white immigrant groups, of course, but the guidelines made no mention of

that.) It was necessary to monitor how the nonwhite races were faring in the

present in order to overcome the allegedly lingering remnants of a history of

white supremacy. The three minority races were victim groups that had once “suffered

discrimination and differential treatmenton the basis of their race.”As

victims, they were—and are—entitled to a variety of special protections and

preferential programs not available to whites.

Does

it make sense at the end of the twentieth century to identify “races” as

defined by nineteenth-century supporters of white supremacy? The authors of

Directive 15 were careful to say that “these classifications should not be

interpreted as being scientific or anthropological in nature.” True enough, but

the admission only makes their decision to utilize them more dubious. If these

categories are not “scientific” or “anthropological,” what are they? Why should

the U.S. government distinguish some citizens from others on a basis that is

not “scientific” or even “anthropological” (whatever that means) and use those

distinctions in allocating public resources? Perhaps the answer is that the OMB

assumed that Americans today habitually draw these crude distinctions in their

daily lives, and that recognition of social reality requires the government to

do the same. This is a feeble argument. What is the evidence of a societal

consensus on precisely these distinctions? Some Americans may see the

population as divided into two groups, whites and nonwhites. Some, on the other

hand, may make much finer distinctions than these racial categories provide,

seeing Japanese Americans as quite different from Korean Americans, for

example. It is certainly questionable whether Koreans and Japanese feel a

strong sense of kinship and solidarity as “Asians”; there is considerable

antipathy between these groups that grows out of the fact that Korea was under

Japanese rule for most of the first half of the twentieth century. Immigrants

from Ethiopia and Jamaica likewise differ from blacks whose ancestors came to

North America as slaves centuries ago, but those differences are obscured when all

are thrown together into the black racial category.

Even

if it could be shown that these unscientific racial categories did correspond

at least moderately well to the way in which the general public perceives the

racial landscape, it does not follow that it is wise for the government to

insist upon the saliency of race. Justice Harry Blackmun argued two decades ago

that “in order to get beyond racism, we must first take account of race. . . .

And in order to treat some persons equally, we must treat them differently.”6 But

the race-conscious policies that have been pursued in the United States for a

generation have plainly not taken us “beyond racism.”7

President

John F. Kennedy was wiser than Justice Blackmun, I believe, when he said that “race

has no place in American life or law.”8 To continue to draw racial

distinctions in our laws and to compile massive amounts of official statistical

data about racial differences among racial groups will not serve to make race

less important in “American life.” We need not go so far as to bar government

from collecting any information whatever about the ethnic composition of the

population. But the evidence necessary to monitor the socioeconomic progress of

groups and to identify problems can be obtained without pertetuating the

dangerous fiction of race. The census currently includes a question about the “ancestry

or ethnic origin” of respondents, a concept broad enough to include African

Americans, Asian Americans, and all other Americans. The answers to this

question will yield information about what arenow classified as racial groups

without contributing to the fallacy that they are fundamentally different from

other groups based on a sense of common origins and peoplehood.

Is

Racial Victimization Hereditary?

The rationale

for making racial distinctions in official statistics is remedial. Directive 15

rests on the premise that being a member of a particular race that was treated

unfairly at some point in the past leaves an indelible imprint on everyone with

the same “blood.” Is there no statute of limitations for complaints of

historical victimization? Does the discrimination experienced by your

grandparents, great-grandparents, or even more remote ancestors have any

relevance to your life today?

The

case for classifying some Americans as belonging to a victim group is, of

course, strongest for blacks. Indeed, it is hard to imagine that official racial

statistics would still be gathered but for the continuing “American dilemma,”

the seemingly never ending problem of how black Americans can be integrated

into American society. The situation of blacks in the United States is sui generis.

Although there are many points of resemblance between African Americans and

immigrant groups that also encountered prejudice and discrimination, the

differences are fundamental. No other group has such a bitter heritage of

centuries of enslavement, followed by several decades of disfranchisement and

legally enforced separation and subordination in the Jim Crow South and by

intense racist hostility in the rest of the country.

Nonetheless,

in spite of this unique history, the assumption that blacks today should still

be regarded as victims who must be treated “differently” in order to be treated

“equally” is mistaken. African Americans made stunning educational and economic

advances in the 1940s and 1950s, which made possible the triumph of the civil

rights revolution and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, and since then they have continued to make gains.

And white racial attitudes have changed dramatically for the better.9 Anti-black

racism has by no means disappeared altogether, but it is no longer the chief

obstacle in the way of further progress by African Americans.

Note,

for example, that more than seven out of ten black babies today are born out of

wedlock, and that fully 85 percent of black children living in poverty reside

with a mother and no father.10 Suppose that these children had the same mothers

and (absent) fathers and lived in the same neighborhoods but had somehow

arrived in the world with white skins. If these children were all “white,”

would their life prospects be notably better? It seems highly doubtful. Or

consider the dismal fact that the average black twelfth-grader today reads at

the same level as the average white child in the eighth grade and is about as

far behind in math, writing, and science.11 In an economy that increasingly

rewards those with strong cognitive skills, this pattern of low educational

achievement guarantees that African Americans will be disproportionately

concentrated in the least attractive and poorest-paid jobs. Again, if they had

the same limited cognitive skills but white skins, it would not improve their

job prospects significantly.

With

other “racial” groups, the assumption that exposure to discrimination in the

past continues to be a major obstacle is even more questionable. During World

War II, Japanese American citizens living on the West Coast were presumed to be

of questionable loyalty to the United States because of their “blood” ties to

Japan, and for that reason they were forced to abandon their homes and

businesses and were locked up in relocation camps for the duration of the war.

Almost all of them were deprived of their liberty for four years, and many lost

valuable property, receiving only partial compensation long after the war had

ended. But by 1990 native-born Japanese Americans had median family incomes 47

percent higher than those of whites, and they were 57 percent more likely to have

a college degree.12 Some doubtless still bore psychic scars from their

bitter experience half a century before, but that did not prevent the

dramaticupward mobility of the group in the postwar years. By 1990 most of

those who been locked up because of their race were retired or dead; two-thirds

of the Japanese Americans then alive had been born after the relocation camps

had been shut down.13 And yet Japanese American entrepreneurs today are

given an edge over whites in the competition for federal contracts (and state

and local governmental contracts in many places) because they belong to the Asian

“race.”

An

even more strained historical argument has been made about another Asian

group—Chinese Americans—in the recent report of the Advisory Board to the President’s

Initiative on Race. The report speaks of “the forced labor of Chinese Americans”

as part of “a history of legally mandated and socially and economically imposed

subordination to white European Americans and their descendants.”14 This

is a lurid and tendentious description of the “coolie” system, a form of

indentured servitude in which Chinese merchants advanced passage money to

America to unskilled workers who then paid off their debt through labor. But

even if the coolie system was as bad as the quoted characterization, how is the

indentured labor of the Chinese in California in the 1870s relevant to the

situation of Chinese Americans in the 1990s? Chinese immigrants did indeed

encounter horrendous prejudice in the nineteenth century and after, but the

1990 Census revealed that native-born Chinese Americans were even more

successful than the enormously prosperous Japanese Americans, with median

family incomes some 58 percent higher than those of whites.15 But

Chinese Americans are nonetheless favored over whites in various public

contracting programs on the assumption that their “race” remains a major

handicap.

If the

connection between the coolie system or the internment camps and the Chinese

and Japanese Americans of today is tenuous, it shrinks to the vanishing point

when this purported link is extended to all persons of Asian “race.” It happens

that more than four out of five Asian American adults living in the United

States today were born abroad; indeed, almost all the foreign-born have arrived

in the past three decades, at a time when anti-Asian prejudice was disappearing

and public commitment to equal treatment for all Americans had brought about

strong federal legislation to combat racial discrimination.16 Many

of these newly arrived Asians— Koreans, Cambodians, and Vietnamese, for

example—are from countries that sent virtually no immigrants to the United

States before World War II, so there was no history at all of racism against

their ancestors in the United States. The earlier mistreatment of Chinese and

Japanese Americans did nothing to dissuade these newcomers from moving to

America in search of greater opportunity, nor should it have. It had no bearing

whatever on their prospects for a better life in contemporary America.

The

Invention of “Hispanics” as a Quasi-Racial Group

In

addition to the three groups presumed to be disadvantaged because of their

race, Directive 15 added a fourth—”persons of Hispanic origin.”17 When

the OMB issued its guidelines in 1977, the number of Mexican Americans in the

United States had been growing dramatically, and immigration from Central and

South America was also accelerating. Disproportionately large numbers of the

newcomers from Latin countries had poorly paid unskilled jobs and family

incomes below the poverty line.

Were

their economic difficulties due largely to prejudice against them, or were they

due to the fact that they had arrived in the United States with little

education, limited or no command of English, and few marketable skills? The OMB

did not even acknowledge the question. Directive 15 assumed that the depressed

economic and social position of Hispanics was mainly the result of racism and

that federal agencies accordingly must compile statistics on the group and do

as much as possible to assist them.

Another

problem with the “Hispanic” concept was the attitude of the so-called Hispanics

themselves, most of whom did not regard themselves as members of a nonwhite “race.”

Although activists from the group insisted that they were “people of color,”

that was not the perception of most of those they claimed to speak for. People

of Hispanic ancestry typically identified themselves as whites on the census

and other official forms that included a race question—marriage licenses and

birth and death records, for example.18

At one

point earlier in the century, Mexican Americans were categorized as nonwhite by

the census takers, and the results were instructive. In 1930 the Census Bureau

departed from its earlier practice of classifying Mexican Americans as white

and instead employed a Mexican “race” category. Enumerators were to use it for “all

persons born in Mexico, or having parents born in Mexico” who in their judgment

were “not definitely white.”19 People of Mexican ancestry were lumped together with

blacks, Asians, and American Indians in the reported totals for “nonwhites.”

After Mexican American organizations and the Mexican government furiously protested

the decision to relegate members of the group to the nonwhite category, census

officials abandoned the categorization and restored Mexican immigrants and

their children to the white column.20

This

pattern of racial identification continues today also and applies not only to

Mexican Americans but also to other Hispanics. Although Latinos tend to have

darker skins than the typical American of European ancestry, a large

majority—95.7 percent, according to a 1991 Current Population Survey—report

themselves to be white.21 And very few of those who reject the white

designation identify with any of the other three races; they think of

themselves as being of racially mixed origins, rejecting the Census Bureau’s

traditional view that everyone belongs in one and only one racial box.

To

overcome this awkward difficulty—alleged victims of racism who did not belong

to a nonwhite race—the OMB created a new category, “Hispanic.” According to

Directive 15, Hispanics were frequently the objects of prejudice and “differential

treatment,” not because of their “race” but because of their “ethnicity.”

Federal agencies were required to compile data on Hispanics as well as on the

three nonwhite races because “ethnicity” for Hispanics was presumed to be the

functional equivalent of race for blacks, Asians, and American Indians.

The

concept of “ethnicity” had long been an essential analytical tool for

understanding American society, but Directive 15 used the term in a novel,

indeed bizarre, way. The common understanding of American society was that

immigration had played a central role in its development and that many distinct

“ethnic groups” had emerged out of the immigration experience and then faded

away as later generations became more integrated into the larger society. Being

a stranger in a strange land was difficult, and newcomers naturally felt the

need to associate with other people who spoke their native tongue, liked

similar food, worshiped in the same way, and had similar customs and values.

The Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups describes

more than one hundred such ethnic groups, many of them extinct or close to it

by now.22

It is

thus remarkable that the official guidelines employed by the federal government

maintain that there are just two ethnic

groups in the United States: persons of “Hispanic origin” and those “not of

Hispanic origin.”23 Several dozen white ethnic groups with distinct

identities were suddenly collapsed into a single group with the awkward label “not

of Hispanic origin.” All the white ethnic groups had presumably merged into the

general population, while Hispanics were taken to be an unassimilable,

race-like group that would be as enduring as the “races” that the federal

government was so dedicated to enumerating—even though most Hispanics

considered themselves, and had always been officially classified as, “white.”

Equally

dubious was the assumption that the umbrella label “Hispanic” designated a

coherent entity with a common historical experience of oppression at the hands

of white Americans. What do Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans,

Argentineans, Colombians,Venezuelans, Chileans, and more than a dozen other

immigrant nationalities from Central or South America really have in common?

Not even some variant of the Spanish language as their mother tongue, because

the label has been defined to include people who trace their origins to

Portugal or Brazil and are Portuguese-speakers. And it includes a variety of

Indian peoples whose home language is not Spanish. Perhaps most remarkably, the

rubric includes the descendants of roughly three-quarters of a million

immigrants from Spain or Portugal, although no one could seriously argue they

have encountered more prejudice in the United States than immigrants from countries

like France, Italy, Poland, or Greece. The category Hispanic is more like the

category European than the category Italian or German, and no scholar considers

the dozens of American ethnic groups that derive from Europe a single ethnic

group with a common experience.

A

majority of the Americans now designated as Hispanic are Mexican Americans, and

the case for viewing their history as one dominated by “racism and oppression”

cannot withstand critical scrutiny either. The report of the President’s

Initiative on Race advances this charge, speaking of “the conquest and legal

oppression of Mexican Americans and other Hispanics.”24 This

is absurdly oversimplified history. The five southwestern states from New

Mexico to California were indeed once part of Mexico and were annexed to the

United States at the end of a war between the two nations in the 1840s. But

only a tiny fraction of the Mexican American population today can trace their

origins to that conquest. A mere 13,000 people born in Mexico were recorded as

U.S. residents in the Census of 1850, and they were people who had chosen to

remain and live under American rule following the Mexican War.25 Mexican

Americans did not become a quantitatively significant element of the U.S.

population until well into the twentieth century. As late as 1910, they were no

more than 0.4 percent of the total U.S. population.26 The

real growth of the group was the result of a huge wave of immigration from

Mexico that began during the World War I decade, an immigration that was

basically similar to the peasant migrations from eastern and southern Europe

early in the century. Another much larger immigration wave from Mexico began in

the 1950s and continues today.

The

idea that the lives of Mexican Americans are somehow blighted by a legacy of “conquest”

makes no sense unless one assumes that the historical memory of having lost

territory to the United States a century and a half ago is somehow carried in

the blood of everyone of Mexican American descent. Immigrants from Mexico who

arrived in the twentieth century encountered prejudice, of course, but whether

the hostility was any greater than that met with by Italians, Poles, or Jews is

questionable. Certainly they were not subjected to “legal oppression”

comparable to what blacks experienced in the Jim Crow South.

Because

of their strong historical concentration in the Southwest and their traditional

employment as farm laborers, Mexican Americans tended to have low incomes and

limited opportunities to obtain an education that would facilitate their

mobility in the larger society. In recent decades, movement out of rural areas

and agricultural occupations has gradually resulted in the growth of a Mexican

American middle class, at a pace comparable to that of groups like Italians and

Poles earlier in the century. The impressive upward mobility of Mexican

Americans has been obscured, however, by the continuing influx of large numbers

of relatively uneducated immigrants from Mexico, both legal and illegal, whose

lowly status pulls down the average for the group as a whole.27

To

view American society as divided into four separate, watertight compartments

called “races,” with a fifth compartment for a “Hispanic” race that is not

quite a race, is profoundly misleading. So is the assumption that public policy

should be based on the assumption that three of these races and the Hispanic

ethnic group have been oppressed and victimized by the white majority for so

long that they need preferential treatment in education, employment, and public

contracting into the indefinite future.

The

Myth of the Impending Minority Majority

The

picture of the American people as divided into oppressors and oppressed

racial-ethnic groups is an oversimplification and a distortion. The errors it

entails are compounded when we attempt to peer into the future and calculate

what the racial and ethnic mix of the American population will eventually be.

Projections of precisely this kind have attracted considerable public

attention, thanks to a credulous press. The cover story in the April 9, 1990,

issue of Time featured a Census Bureau projection that concluded

that the United States would have a “minoritymajority” population by the year

2050, Since then, the official estimates have been revised slightly, with the

latest indicating that the “minority” population (blacks, Asians, Hispanics,

and American Indians) will be a shade less than a majority in 2050—49.7 percent

of the population.28 Will this in fact happen? Will it matter if it

does? The first thing to notice is that demographers have never been much good

at prediction. In the l930s, population experts were unanimous in foreseeing a

sharply declining population in the U.S. and other industrial societies. Not

one predicted the postwar Baby Boom or the resumption of mass immigration to

American shores. In the past half century, instead of declining, the U.S. population

has almost doubled. Demographers project future populations on the basis of

currently observable patterns of immigration, fertility, and mortality. The

more remote the future, the greater the possibility that these variables will

change in unanticipated ways.

Indeed,

the Census Bureau recognizes some of the uncertainty by issuing a series of

different projections of the expected population at various future dates. The

projection cited above is based on the “middle series” estimate, which puts the

total U.S. population at 394 million in 2050. But the “low series” estimate the

bureau makes for that year is just 283 million, and the “high series” estimate

is 519 million.29 The high and low estimates vary from each other by

a staggering 236 million. Thus the population half a century from now may be

nearly double what it is today (approximately 270 million), but it might

instead be a mere 5 percent larger than it is now. If there is such great

uncertainty about what the total population will be half a century from now, there

must be similar uncertainty about the size of the various racial and ethnic

subgroups that make up the total.

Why do

these projections vary so enormously? Because they necessarily rest on

assumptions about the determinants of population growth that may prove

mistaken. For example, they require accurate estimates of the level of

immigration to the United States thirty or forty years hence. Obviously, we

cannot know that with any reliability because our immigration policy may become

far more restrictive than it is now. Laws enacted in the 1920s sharply cut back

on the number of new arrivals, and we cannot be sure that a similar

anti-immigrant backlash will not again close the door to newcomers from abroad.

Nor

can we be at all sure about a second variable that determines how the size of a

population changes over time—its fertility patterns. (Changes in mortality

rates can also affect population size, but mortality usually does not fluctuate

dramatically enough to make a big difference, except in the case of demographic

catastrophes like the Great Plague of the fourteenth century.) At the beginning

of the twentieth century, a greatmany Americans of native stock worried about

the consequences of their own rapidly declining fertility. Many feared that

they were being swamped by huge waves of new immigrants and the large families

the new arrivals typically had. Lothrop Stoddard, a leader of the Immigration

Restriction League, warned that Anglo-Saxons were committing “race suicide.”

According to his calculations, after 200 years 1,000 Harvard men would have

left only 50 descendants, while 1,000 Romanian immigrants would have produced 100,000!30

There

was nothing wrong with Stoddard’s math. The problem lay with his straight-line

projection of the fertility differentials of his day 200 years into the future.

He failed to comprehend that in the second and third generations Romanian

Americans would adjust their fertility patterns to the American norm and would

produce many fewer children than did the immigrant generation.31

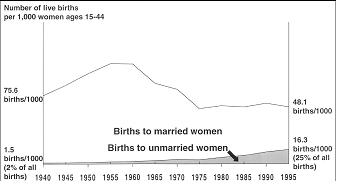

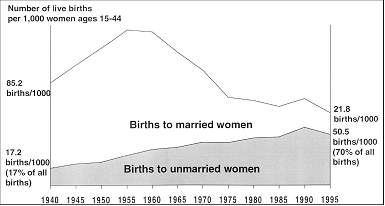

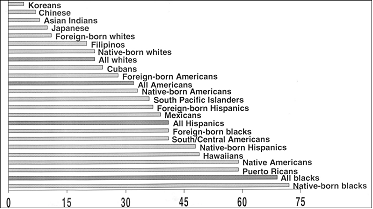

This