Ethics Articles

Articles: Wealth

>> = Important Articles; ** = Major Articles

Number of Billionaires Up to Record 793 (Foxnews, 060309)

Driving Alone—America’s Commuter Society (Mohler, 060505)

Charitable Giving in U.S. Nears New High (Christian Post, 060619)

==============================

Free Methodist Manual

630.2.2 Self Discipline

One attribute of the Spirit’s indwelling presence is self-control (Galatians 5:23). The Scriptures instruct us to honour the body as the temple of the Holy Spirit (I Corinthians 6:19-20).

As Christians we desire to be characterized by balance and moderation. We seek to avoid extreme patterns of conduct. We also seek to keep ourselves free from addictions or compulsions.

Since Christians are to be characterized by a disciplined style of life, we attempt to avoid selfish indulgence in the pleasures of this world. It is our wish to live simply in service to others, and to practice stewardship of health, time, and other God-given resources.

We are committed to help every Christian attain such a disciplined life. Although unhealthy habits are not easily broken, believers need not live in such bondage. We find help through the Scriptures, the Holy Spirit, prayer, and the counsel and support of other Christians.

630.2.3 Stewardship Of Possessions

Although as Christians we accumulate goods, we should not make possessions or wealth the goal of our lives (Matthew 6:19-20; Luke 12:16-21). Rather, as stewards we are people who give generously to meet the needs of others and to support ministry (II Corinthians 8:1-5; 9:6-13).

The Scriptures allow the privilege of private ownership. Though we hold title to possessions under civil law, we regard all we have as the property of God entrusted to us as stewards.

Gambling contradicts faith in God who rules all the affairs of His world, not by chance but by His providential care. Gambling lacks both the dignity of wages earned and the honour of a gift. It takes substance from the pocket of a neighbour without yielding a fair exchange. Because it excites greed, it destroys the initiative of honest toil, and often results in addiction. Government sponsorship of lotteries only enlarges the problem. Because of the evils it encourages, we refrain from gambling in all its forms for conscience’ sake, and as a witness to the faith we have in Christ.

While customs and community standards change, there are changeless scriptural principles that govern us as Christians in our attitudes and conduct. Whatever we buy, use, or wear reflects our commitment to Christ and our witness in the world (I Corinthians 10:31-33). We therefore avoid extravagance and apply principles of simplicity of life when we make choices as to the image that we project through our possessions.

==============================

Number of Billionaires Up to Record 793 (Foxnews, 060309)

NEW YORK — As emerging stock markets surged during the past year, 102 wealthy people around the world won a much-coveted title along with their stellar gains — they all became billionaires.

The number of billionaires around the world rose by 102 to a record 793 over the past year, and their combined wealth grew 18 percent to $2.6 trillion, according to Forbes magazine’s 2006 rankings of the world’s richest people.

Forbes editor Luisa Kroll noted that Russia’s stock market jumped 108 percent between February 2005 and February 2006, while India’s market rose by more than 54 percent during the same period. Brazil “was another bright star” with a market gain of 38 percent, she said.

Kroll said the changes on the list weren’t driven by U.S. investments.

“The more exciting story is these emerging markets,” she said. “The U.S. stock market was quite a laggard with only a 1 percent increase.”

Such tepid returns ate into the fortunes of some of the richest Americans, including the founding family of Wal-Mart Stores Inc.

The growth in emerging markets also meant the Czech Republic placed a billionaire on the list for the first time: Petr Kellner, who debuted at No. 224 with $3 billion. And while China’s market grew just 3 percent, the country added eight more billionaires, up from two last year.

Microsoft Corp. founder Bill Gates was again the world’s richest man for the 12th year running. Gates grew wealthier, with his net worth rising to $50 billion from $46.5 billion. Investor Warren Buffett, the chairman of Berkshire Hathaway Inc., again ranked second; his fortune fell by $2 billion to $42 billion.

The rest of the top 10 underwent a major reshuffling, with three familiar names dropping out of that select group: German supermarket company owner Karl Albrecht, Oracle Corp.’s Lawrence Ellison and Wal-Mart chairman S. Robson Walton.

Mexican telecom mogul Carlos Slim Helu moved up one notch to No. 3 with $30 billion, replacing Indian steel magnate Lakshmi Mittal, who fell one place to No. 5 with $23.5 billion.

Ikea founder Ingvar Kamprad of Sweden rose two slots to No. 4 with $28 billion.

Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen edged up to sixth place from No. 7, with a net worth of $22 billion. He was followed by France’s Bernard Arnault, chairman and chief executive of LVMH and The Christian Dior Group, with $21.5 billion; Arnault was new to the top 10.

Saudi Arabian Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Alsaud fell to eighth place from No. 5, with $20 billion; and Canadian publisher Kenneth Thomson and his family moved into the top 10, ranking No. 9 with $19.6 billion.

Hong Kong’s Li Ka-shing rose to No. 10 with $18.8 billion. Ka-shing is the chairman of Cheung Kong (Holdings) Ltd. and Hutchinson Whampoa Ltd.

The Walton family, which dominated the upper echelons of the Forbes list in recent years, tumbled in this year’s ranking as stock in the world’s largest retailer dropped more than 10 percent in the past year.

S. Robson Walton, known as Rob, who last year ranked 10th, fell to 19th with $15.8 billion. Christy Walton and Jim Walton tied for 17th with $15.9 billion each, while Alice Walton followed Rob Walton at $15.7 billion. Helen Walton, mother of the clan, did not make it into the top 20, landing at No. 21 with $15.6 billion.

Martha Stewart, who was new to the list last year, dropped off completely this year. Her fortune shrank from $1 billion to an estimated $500 million following her conviction for lying about a stock sale and her five-month prison term.

Investors in new industry sectors popped up on this year’s list, most notably those with holdings in alternative energy and online gaming.

Australian Shi Zhengrong, ranked No. 350, made his $2.2 billion fortune through his solar energy company out of China. India’s Tulsi Tanti, whose company owns Asia’s largest wind farm, arrived at No. 562 with $1.4 billion after his company went public in October.

J. DeLeon and Ruth Parasol, both of the United States and tied for No. 428, represented the online gaming industry with $1.8 billion each. Interestingly, most of their company’s revenue comes from the United States, where online gaming is illegal, Kroll said.

“Somehow, they have been able to skirt that,” Kroll said.

Parasol is also one of the 10 new women to make the list and the only female newcomer to be self-made. Only six of the 78 female billionaires are self-made; most attained their wealth through marrige or inheritance.

The youngest billionaire is also female. Hind Hariri, daughter of slain Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, is 22 years old and eight months younger than Germany’s Prince Albert von Thurn und Taxis.

The methodology of the rankings remains consistent with years past, Kroll said. The magazine confirmed the worth of an individual’s holdings in public companies by using the Feb. 13 closing stock price, and estimated the value of private companies by looking at comparable public firms in the industry and by consulting with experts in the field.

Forbes calculated the value of real estate by square footage minus any debt on the properties.

==============================

Driving Alone—America’s Commuter Society (Mohler, 060505)

According to the U. S. Census Bureau, the fastest growing group of American commuters are those who travel more than 90 minutes to work, and then another 90 minutes back home. For many Americans, life is increasingly lived behind the driver’s wheel and the interior of the automobile is becoming the most familiar “living” space for many harried Americans.

In its May 1, 2006 edition, Newsweek offers a unique perspective into the lives of what reporter Keith Naughton calls “extreme commuters.” These workers drive from 50 to nearly 200 miles each way, to and from their place of work. Most leave well before the break of dawn and many return well after the sun has set. After the Industrial Revolution itself, this revolution in the way Americans work and spend their time getting to and from work may represent the largest single transformation in the way many Americans live.

Naughton introduces his readers to commuters such as Dr. Bill Small, a Chicago physician who begins his two-hour commute into downtown Chicago at 6:00 a.m. The doctor has his entire commute planned, right down to the smallest detail. “Small’s routine is so finely tuned that he won’t stop for coffee if there are more than three cars in the drive-through. Today there are just two, and he picks up an extra-large. But there’s no time for a bathroom break, so Small, 41, won’t allow himself a single sip for nearly an hour.”

Dr. Small, who lives with his wife and children in St. Charles, Illinois, a town nearly fifty miles west of Chicago, says that he prefers living in St. Charles because, “It’s a nice place to raise kids . . . And it does feel like you’re away.”

Similarly, 34-year-old Web designer Vincent Driscoll gets up at 4:00 a.m. to make his 55-mile commute from Pennington, New Jersey to Jersey City. In order for his system to work, Driscoll must catch a 5:15 a.m. train to Newark and then switch to another train which will deliver him to Jersey City, if everything goes on schedule, by 7:00. “By Friday night, I’m completely wiped out,” Driscoll laments. “My wife says I’ve become an old man.”

The phenomenon of extreme commuting did not emerge out of a cultural vacuum. For some time, economic and social pressures have driving workers further and further from their places of employment. In most cases, the pressure is probably financial. In order to purchase a family home, complete with yard and suburban neighborhood, employees, professionals, and other workers are now driving more than an hour to work. Indeed, almost ten million Americans now drive more than an hour to work, and that represents a jump of 50 percent from just 1990. According to Newsweek, the average commute is now 25 minutes, up 18 percent from 20 years ago.

Interestingly, Newsweek points to the phenomenon of “driving ‘til you qualify,” as a primary factor. “New home prices have nearly tripled in the past 20 years,” Newsweek explains, “and now average almost 300,000 dollars, according to the National Association of Home Builders. In places like southern California, each exit along the interstate saves you tens of thousands of dollars.”

As workers live further and further from their places of employment, the departure time in the morning gets earlier and earlier and the complications mount. The fastest-growing time for departure to work is now between 5:00 and 6:00 a.m. More Americans are leaving earlier and getting home later than ever before.

“This endless commute is becoming the defining characteristic of the 21st-century working stiff,” Newsweek asserts. “So much of what we worry about today—volatile real-estate prices, sleeplessness, our overstressed lives—all merge together on the road, as we search for the elusive simple life in some suburban Shangri-La.”

Some wonder if the commute is worth it. “How much is it worth to own your own home if you end up spending four hours on the road and not playing with your kids, not sleeping enough, and rotting in traffic?,” asks Joy Mander, a nurse who drives 45 miles to work at Children’s Hospital in Oakland, California.

Automobile designers and traffic engineers are scrambling to meet the challenge posed by so many long-distance commuters. Newsweek reports that the automobile’s dashboard “is becoming the nation’s dinner table, and the drive-through its kitchen.” As Harry Balzer of NPD Group, a research firm, explains: “The fastest-growing appliance in America is not the microwave . . . it’s the power window.”

All this points to a tremendous cost in time and absence from home. The impact on family life can be obvious—many fathers (and an increasing number of mothers as well) leave home before their children get up in the morning and return just as their children are getting ready for bed. Dad has simply missed out on the normal rhythm of family life, available only in emergencies or during cherished weekends.

A few years ago, a father involved in his own form of “extreme commuting” told me that his children were perfect angels. As he quickly explained, he saw them as angels because that’s the way they appear while sleeping, and his main opportunity to see his children was as they slept in their beds when he returned home from work, and were still there as he left for work the next morning.

This separation of parents from children is now alarming public safety officials. John Brooks, an economic analyst in Palmdale, California, warns of the possibility of a real-life disaster. “We’re really worried about what happens in an earthquake. All the parents are down below, and we’ve got tens of thousands of their kids up here to take care of.” The “down below” means Los Angeles and the “up here” means the exploding suburbs north of the L.A. basin.

The cost of the society is evident in the fact that so many parents are separated from the lives of their children, at school and in other activities, as well as at home. “With everyone stuck in traffic, it turns out there’s no one around to coach Little League or volunteer for the PTA, not to mention get dinner on the table,” Naughton observes.

The impact of the commuting culture was noted by Robert D. Putnam in his much-respected book, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, published in 2000. “Suburbanization of the last thirty years has increased not only our financial investment in the automobile, but also our investment of time,” Putnam noted. “Between 1969 and 1995, according to government surveys of vehicle usage, the length of the average trip to work increased by 26 percent, while the average shopping trip increased by 29 percent.”

Not only are Americans spending more time in their automobiles, they’re spending most of this time alone. Two-third of all automobile trips are made alone—a figure that continues to rise.

“One inevitable consequence of how we have come to organize our lives spatially is that we spend measurably more of every day shuttling alone in metal boxes along the vertices of our private triangles,” Putnam observes. In his analysis, the car and the commute are “demonstrably bad for community life.”

For many workers, the picture is getting even worse. Over the last thirty years, college-educated professionals have been working longer and longer workdays, even as their commuting time takes up even more precious hours. Maintaining their families in a suburban lifestyle means that many professionals are simply away from the family for almost all of the waking day, connecting only by telephone and precious weekends or days off.

Robert D. Putnam’s concern is the contribution of the commuting culture to the breakdown of community. As citizens are spending more and more time driving automobiles to and from work, they have much less time to contribute to civic involvement.

Pastors are recognizing the same phenomenon. Hard-pressed families find themselves pulled in many directions, and connections to the vibrant life of the faithful local congregation are often interrupted or broken by the same stresses and strains that tear at family life. Workers who spend more and more hours behind the wheel have fewer hours to contribute to church activities and other Christian involvements.

The most immediate toll of all this is found inside those suburban homes workers are trying with such fervor to maintain, even if they spend most of their waking hours far away. The stresses on family life are obvious—many wives feel almost abandoned by their husbands as they maintain domestic life and take care of the children while dad is away. “I feel like a single parent,” said Laura Neelley, whose husband, Chris, commutes 120 minutes to and from his job in Los Angeles. As the couple told Newsweek, Chris leaves home just after 7:00 a.m. and returns after 8:00 p.m., when dinner is over and the children are in their pajamas.

The Newsweek article acknowledges the pressures and patterns that have contributed to this phenomenon. The emergence of vast metropolitan areas, with far-flung suburbs existing as oases of affordable housing, has produced a context in which “extreme commuting” begins to make sense to many workers and their families.

Are there limits to further growth in commuting distance and the time involved in getting to and from work? The prospects do not look hopeful. Indeed, a different group of commuters is pushing daily travel to the extreme—catching airline shuttles and trading daily time in the car for time on an airplane.

Christians must ask some basic questions about “extreme commuting” and what it means for family life. This is true even for those whose commute takes much less than 90 minutes each way. Have we reached the point that we have simply accepted cultural assumptions about the importance of work and the value of home ownership to the point that we are putting our own families and spiritual lives at risk?

There are no easy answers to this question. Those who call for a fundamental restructuring of the American economy are fighting patterns that have now been building for more than half a century and show no signs of abating. In any cultural or economic context, Christians must struggle to understand what faithfulness would demand in terms of family, home, church, and professional responsibilities. Anyone who suggests that navigating these waters in postmodern times is easy is simply denying reality.

Nevertheless, we must admit that it is all too easy to buy into the prevailing model of the American dream, and to trade family time and involvement for a vision of a larger home, a larger lawn, and a larger mortgage. Christians had better make some fundamental decisions about how much time we are willing to spend behind the wheel, in our cars, away from our families, churches, and communities. Otherwise, the automobile will soon represent, not only our dining rooms, but our bedrooms, living rooms, and sanctuaries as well.

==============================

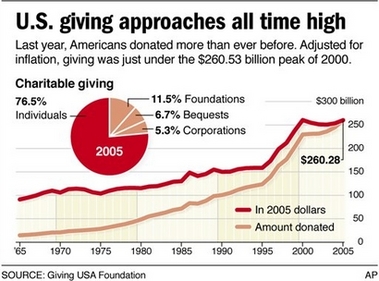

Charitable Giving in U.S. Nears New High (Christian Post, 060619)

NEW YORK (AP) - The urgent needs created by three major natural disasters — the tsunami in Asia, earthquake in Pakistan and hurricanes Rita, Katrina and Wilma — drove American philanthropy to its highest level since the end of the technology boom, a new study showed.

The report released Monday by the Giving USA foundation estimates that in 2005 Americans gave $260.28 billion, a rise of 6.1 percent, which approaches the inflation-adjusted high of $260.53 billion that was reached in 2000.

About half of the overall increase of $15 billion went directly to aid victims of the disasters. The rest of the increase, meanwhile, may still be traced to the disasters since they may have raised public awareness of other charities.

“When there is a very significant need, when people are clearly aware of that need, they will respond,” the chairman of Giving USA, Richard Jolly, said. “Were it not for the disasters, what we would have expected is more of a flat number. With the staggering need generated by the disasters, it’s very in keeping with what has happened in the past — the American public stepped forward and provided additional support.”

The three natural disasters generated about $7.37 billion, which was 2.8 percent of total giving. Of that amount, individuals contributed $5.83 billion, or 79 percent, while corporations added $1.38 billion, or 19 percent.

Excluding disaster relief, the report indicates that there still would have been a rise in gifts from both individuals and corporations. In the 41 years that Giving USA has tracked philanthropy, giving has increased with the wealth of the nation. Since 1965, total contributions have been between 1.7 percent and 2.3 percent of gross domestic product. The highest level was reached at the end of the technology boom in 2000. For 2005, it was estimated to be 2.1 percent of GDP.

Disaster relief may have “crowded out” giving to other recipients of international aid. Without the $1.14 billion in relief contributions, giving to this sector fell to $5.25 billion, a decline of 1.9 percent, or an inflation-adjusted drop of 5.1 percent.

As is usual, individual giving was the largest source of donations, accounting for an estimated $199 billion, or 76.5 percent of the total. For 2005, it was estimated to rise by 6.4 percent, or 2.9 percent adjusted for inflation.

Total corporate giving grew by 22.5 percent to an estimated $13.77 billion, and accounted for about 5.3 percent of overall gifts. That is slightly higher than the 40-year average of 5 percent.

Another recent report, from the Foundation Center, also shows an expected rise in corporate giving. Earlier this month, the center released a report showing an increase in philanthropy by corporate foundations, a subsector that has doubled in size from 1987 to 2004. That study predicts that nearly 2,600 corporate foundations gave $3.6 billion in 2005, a rise of 5.8 percent. The study noted that the growth rate was slower than for other types of foundations.

The director of research at the Foundation Center, Steven Lawrence, said he expected a more modest increase in 2006 over last year. While a majority of those who responded to the survey predicted a rise, the number who expect a decrease had also gone up, an indication that the rate of growth is likely to slow.

One area of gifts that declined in 2005, according to the Giving USA report, were bequests. The report estimates that they fell by 5.5 percent, a drop that is mainly attributed to a decline in the number of deaths in 2004 and an expected decline for 2005.

For the first time since 1998, contributions slated for arts, culture and humanity groups fell. Jolly said the drop could be due to the fact that a few museums had completed major campaigns the year before so were less active in 2005, or that the decline in bequests translated to a decline in arts giving.

The chief executive of Zeum, a nonprofit children’s museum in San Francisco, said the fundraising climate for arts organizations has indeed grown more difficult in recent years. CEO Adrienne Pon said that Zeum, founded in 1998, has seen its fortunes rise and fall with those of technology companies.

Apple Computer Inc. is one of its most prominent supporters and has donated state-of-the-art equipment to the center, where children can create animation, visual art and live performances.

“When we initially opened, we had tremendous support from dot-com era companies,” Pon said. “That was in 1998. Then we started to see in 2000 to 2001, that dropped, and in the last year or two, we’ve seen a resurgence.”

Pon said the majority of Zeum’s funding comes from foundations, such as the Seattle-based Marguerite Casey Foundation, and companies such as UPS.

The Giving USA report was researched and written at the Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University. It has been tracking philanthropic giving since 1965, and in that period, has seen a rise of 185 percent, most of which has been since 1996.

==============================