History: Shroud of Turin - News

News: Firefighters rescue Shroud of Turin (970412)

Thousands queue to see shroud (CNN, 980420)

Shroud of Turin on view for first time in 2 decades (CNN, 980420)

Jerusalem plants found on Shroud of Turin (Foxnews, 990616)

The Shroud of Turin: proof of resurrection? (Website, 040300)

Did boy Jesus look like this? (WorldNetDaily, 041224)

Scientists errred in Turin relic tests, author says (Ottawa Citizen, 990314)

==============================

==============================

News: Firefighters rescue Shroud of Turin (970412)

TURIN, Italy (AP) -- A fire heavily damaged the cathedral housing the Shroud of Turin early Saturday, but firefighters managed to rescue the fabric that some Christians consider to be Jesus Christ’s burial cloth.

“The linen is intact. It’s a miracle,” said Turin Archbishop Giovanni Saldarini, who keeps the shroud on behalf of the pope and the Vatican.

Firefighter Mario Trematore used a hammer to break through four layers of bulletproof glass protecting the urn that contains the 14-foot-long linen shroud, while other firefighters poured water on the vessel to keep it cool.

He collapsed as he rushed outside the San Giovanni cathedral.

“God gave me the strength to break the glass,” he said.

Dozens of Turin residents clapped for firefighters as they carried the silver-and-glass urn from the downtown Turin cathedral, the Italian news agency ANSA reported. Others wept at the sight of the badly damaged cathedral dome.

It took about 200 firefighters more than four hours to extinguish the blaze, which began Friday night. Police said there were no injuries and the cause was not known.

The interior of the cathedral and the neighboring historic Royal Palace, which contains 18th- and 19th-century furniture and valuable paintings, sustained extensive damage.

The cathedral’s altar was badly damaged, and the glass wall separating the cathedral from the chapel broke. A tower in the Royal Palace collapsed.

The Italian television network RAI reported that the fire apparently started in the cathedral’s 314-year-old wooden dome, which was scaffolded for restoration work.

The blaze reached the upper floor of the Royal Palace shortly after the end of a party there attended by U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan and Italian VIPs.

“We smelled smoke, and then we saw the flames raging from the dome,” said Giuseppe Ivano, a palace custodian.

The shroud has been enshrined in the Royal Chapel of the cathedral since 1578. Because of the restoration project, however, it had been moved into the cathedral. Firefighters said that if it had been in its traditional place in the chapel, it would not have survived.

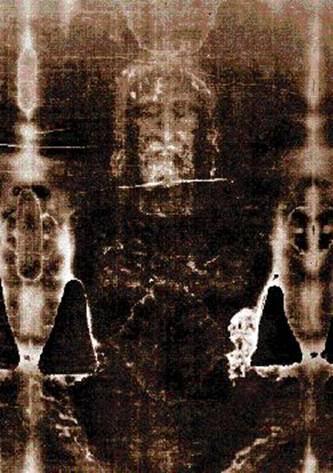

The linen bears the faint yellowish negative image of the front and back of a man with thorn marks on the head, lacerations on the back and bruises on the shoulders.

Though radiocarbon tests in 1988 suggested the shroud was no more than 700 years old, researchers have reached no consensus on how the image was created. The Roman Catholic Church never has claimed the cloth as a holy relic. Some believers say it is the result of a sacred mystery.

In 1353, the linen was taken to France by a crusader and stored in a chapel. It was transferred to Turin after it was slightly damaged by fire in Chambery, France.

Former Italian King Umberto di Savoia gave the cloth to the Vatican in 1983.

A controversial study by Russian professor Dmitri Kouznetsov in 1995 claimed that the Chambery fire modified radiocarbon levels, leading U.S. experts to misdate the shroud.

======================================

Thousands queue to see shroud (CNN, 980420)

THOUSANDS of people queued outside Turin cathedral yesterday for a two-minute glimpse of the Turin Shroud, revered by many as the burial cloth of Christ even though carbon-dating suggests that it is a medieval fake.

Organisers said they expected 50,000 visitors a day between now and mid-June, the first time that the shroud has been displayed publicly for 20 years.

Church officials said there had been complaints that the event was being commercialised, with souvenir stalls selling memorabilia in questionable taste, such as Holy Shroud scarves, T-shirts, chocolate bars, mugs and plates.

Mgr Franco Peradotto, a retired bishop, said he was appalled. Corriere della Sera said: “This is the sort of thing which gives Mediterranean Catholicism a bad name.” In a leading article, the newspaper criticised the Archbishop of Turin, Cardinal Giovanni Saldarini, for announcing that women who had had abortions and “all those who have contributed to abortions” could be absolved of sin by confession to any priest as a special dispensation during the period of the shroud’s display. Abortion is classed as a sin that normally results automatically in excommunication, and only a bishop can readmit the offender to the Church after a lengthy procedure.

The shroud, measuring 14.5ft by 3.5ft, is covered in watermarks, stains and triangular patches, the result of wear and tear and mending after a series of fires over the centuries. On close inspection it shows the faint imprint of a man, bearded, long-haired, 5ft 10in tall, with the marks and bloodstains of crucifixion and flogging on his head, hands and feet, all in accordance with the Gospel descriptions of the Crucifixion and Burial of Jesus.

The image came to light clearly only in 1898, in photographic negatives. Scientists are still unable to explain how the image was formed, how it could have been faked or why it shows no signs of the corpse’s decomposition.

Cardinal Saldarini said that the shroud was being shown “not to satisfy the curious, but as a solemn reminder full of impressive details of the Gospel accounts of the Passion of Jesus”. He ruled out any further tests until after 2000.

The cloth is being displayed at Turin cathedral behind bullet-proof glass in front of the altar.

======================================

Shroud of Turin on view for first time in 2 decades (CNN, 980420)

TURIN, Italy (CNN) --More than 2 million people are expected to visit Turin’s cathedral for a rare glimpse of the mysterious Shroud of Turin, which went on public display Sunday for the first time in 20 years.

Many believe the Shroud of Turin was Jesus Christ’s burial cloth. Its haunting reverse image of a body, including hands, wrists, hollowed eyes, and traces of blood, will be enshrined in a new bulletproof glass case filled with inert gas.

Princess Maria Gabriella, daughter of Umberto II, Italy’s last king, walked the path to the shroud that others will follow.

“To see the shroud had an enormous effect on me,” said the princess. “I don’t know how to describe it. That shroud is truly a presence.”

Scientists are divided over how to explain the 14-foot-long, 3 1/2-foot-wide linen, which bears the image of a man with wounds consistent with Gospel accounts of Christ’s crucifixion.

Carbon-dating tests carried out by experts in Oxford, Zurich and Tucson, Arizona, in 1988 ignited controversy by declaring that the shroud dated between 1260 and 1390 -- more than 700 years after Jesus’ crucifixion in Jerusalem.

The city’s archbishop, Cardinal Giovanni Saldarini, said the church hails the shroud for stimulating “the gift of faith and conversion.”

But new research has given true believers cause for hope.

Two University of Texas microbiologists, Dr. Leoncio Garza-Valdes and Professor Stephen Mattingly, suggest bacteria embedded on the shroud over the centuries could have distorted the carbon-dating result because the micro-organisms may not have been removed by cleaning the cloth before the tests.

Franco Testore, the only university professor of textile technology in Italy and the man who selected the shroud samples used in the 1988 carbon-dating tests, said the research was highly interesting but not yet conclusive.

Theories aimed at refuting scientists’ conclusions can be found among the rash of new books timed for the shroud’s latest display -- one being that pollens found on the cloth bolster arguments the linen might indeed date back to Christ’s days.

Cardinal Saldarini ruled out any further testing until at least 2000, when the shroud will be displayed again. The current display will continue through June 14.

======================================

Jerusalem plants found on Shroud of Turin (Foxnews, 990616)

JERUSALEM (June 16) - The remnants of pollen grains and leaves from vegetation found only in the greater Jerusalem area have have been found on the Shroud of Turin, which according to Roman Catholic tradition was used to wrap Jesus after the crucifixion.

The findings were reported last night by the Hebrew University’s Avinoam Danin and the Antiquities Authority’s Uri Baruch at a special session of the 7th International Conference of the Israel Society for Ecology and Environmental Quality Sciences being held in Jerusalem.

The researchers said that re-examination of pollen grains collected in 1973 and 1978 and investigations of plant images observed on several sets of photographs allowed them to reach certain conclusions regarding the types of plants.

The image of a cluster of thorny thistle (Gundelia tournefortii) was detected in photographs of the shroud made in 1898, 1930, and 1978. The pollen of this species accounts for most of the pollen remnants found on the shroud. According to tradition, this is the type of thistle used to make a crown of thorns for Jesus before the crucifixion.

It is believed to grow only in Israel. The shroud also shows images of the leaves of Zygophyllum dumosum, also found in the Jerusalem area.

“These plants lead us to state that the Shroud of Turin existed before the 8th century; that it originated in the vicinity of Jerusalem; and that the assemblage of plants became part of the shroud in the spring months of March-April,” said Baruch.

He said he completed the work of a Swiss researcher who died 20 years ago. Baruch said he carried out two research projects on the pollen grains found in the shroud’s fiber. “A large number of the grains are compatible with the images which have been detected on the cloth,” he said.

Baruch said however the evidence is not sufficient to claim conclusively that the body wrapped in the shroud was that of Jesus.

The shroud has been in Turin since 1578.

==============================

The Shroud of Turin: proof of resurrection? (Website, 040300)

http://www.canadianchristianity.com/

By Phillip H. Wiebe

This negative, created by a photographer in 1898, shows the likeness of a man¹s face on the Shroud of Turin; markings on the shroud clearly match the various wounds suffered by Jesus of Nazareth. An in-depth analysis of the image is one of the key features of a book by Ian Wilson and Barrie Schwortz, titled Shroud: The Illustrated Evidence (McArthur & Company, 2000).

THE SHROUD of Turin is often considered as nothing more than a curiosity, especially by Protestants. However, its significance for the claim that Jesus was resurrected is arguably quite important.

Three claims need to be demonstrated in order to establish that anyone at all has come back to life. First, we need to show that they were indeed dead, not merely comatose or unconscious. This requirement reminds us of 19th century critics of Christianity who argued that Jesus was not dead when he was removed from his cross. However, few critics of Christian faith now assert that he was not dead; most take for granted that the Romans would not have let him get away alive. The New Testament descriptions of his last moments alive are generally taken to be historically accurate.

Second, we need to show that the dead person was seen alive after death. This is a point that the gospels go to some length to defend, and a point about which many questions have been raised. I argued in Visions of Jesus (Oxford, 1997) that some of these questions can probably be answered, and suggested that experiences in which Jesus is reported to have been seen after the biblical era support the post-resurrection appearance accounts in the gospels. We might say that the textual evidence for the appearances receive important corroboration from nonbiblical experiences.

The third requirement in defending a resurrection is showing that the corpse of the dead person no longer exists. This is particularly important in connection with resurrection claims when no one is present to see it happen.

In the case of Jesus, the fact that his corpse was not found in the tomb where he had been buried is sometimes considered sufficient to show that his body no longer existed. But it could have been in the next tomb, or in the gardener’s shed, or in the ditch behind the cemetery, or in innumerable other places. The New Testament evidence on this point is weaker than is commonly thought. Moreover, no amount of textual evidence can plausibly establish that a corpse has gone out of existence. Something more is required.

X-ray

This is where the Shroud becomes important. The image of the man on its surface not only has properties of a photograph, which the world has known since 1898, but also has properties of an X-ray, seemingly from a body that broke apart at the atomic or subatomic level. The first disciples are said to have marveled at the cloth that wrapped the body of Jesus, but they could not have understood the meaning of its image, if they saw it. That meaning seems to require familiarity with 20th century physics. In the Shroud we might have even stronger evidence for the disappearance of the body of Jesus, as required in a resurrection, than the disciples had on the morning it happened.

Christianity is under close critical scrutiny in Western thought, in part because the achievements of science have taught all of us the importance of evidence, especially when historical claims are at stake. Moreover, the rise of biblical criticism during the last century and a half has shown that the New Testament documents will not be exempted from searching analysis.

We could perhaps say that the attempt to establish essentials of the Christian faith by texts alone -- what could be described as a Protestant project -- has come to an end. Textual evidence must be supplemented by ongoing experience and at least one relic -- the Shroud of Turin. The value of relics is clearly understood by both Catholic and Orthodox branches of the church.

Evidence

The evidence for the claim that a body breaking apart produced the image on the Shroud is complex and circumstantial, but it is impressive. John Jackson, a physicist from Colorado Springs, has done the most important work on the topic. He argues that a number of features of the image can be explained by this conjecture, including the pointillism found in the image, the faint images of bones and teeth and the three dimensional character of the image.

Jackson’s conjecture has been expanded upon by Thaddeus Trenn, a historian of science who taught at the University of Toronto until his recent retirement. Trenn suggests that some external form of energy caused the bonds between the protons and neutrons in the atoms that formed the man’s body to break apart, a phenomenon he describes as weak dematerialization. These protons and neutrons bombarded the cloth immediately adjacent to the corpse, thus producing the pointillistic effect. This was followed by the portion of the Shroud on top of the man then falling through the mix of protons and neutrons, further contributing to the pointillism of the image.

This conjecture explains the three-dimensional character of the Shroud image, which has been known for more than 30 years but never well explained. The image of the nose and chin of the man on the Shroud are darker than his eyes, for example. These varying shades of light and dark depend upon the amount of subatomic material with which the surface was bombarded, which in turn produces enough information in order to create a three-dimensional sculpture of the man. The images of bones and teeth have been defended by Alan Whanger, for years a professor at Duke University Medical Center. They also have examined the enigmatic floral patterns found on the Shroud.

August D. Accetta, a bladder specialist in San Diego, has recently supplied an important corroboration of Jackson’s conjecture. By injecting himself with a radioactive substance, having himself x-rayed, and creating a three-dimensional image of himself, he has been able to show that this image bears some important similarities to the three-dimensional image on the Shroud.

The Christian church has often feared the sciences that have grown out of the Enlightenment. However, more than two dozen scientific and technical disciplines are now involved in the study of the Shroud. Ironically, these sciences could prove to be more supportive of the claim central to Christian thought than anyone could have predicted.

Phillip H. Wiebe will present ‘The Shroud of Turin: Authenticity and Significance for Theology,’ November 15, 7:30 pm, at Block Hall, Neufeld Science Centre, Trinity Western University in Langley. Admission is free.

This negative, created by a photographer in 1898, shows the likeness of a man’s face on the Shroud of Turin; markings on the shroud clearly match the various wounds suffered by Jesus of Nazareth. An in-depth analysis of the image is one of the key features of a book by Ian Wilson and Barrie Schwortz, titled The Turin Shroud: The Illustrated Evidence (McArthur & Company, 2000).

==============================

Did boy Jesus look like this? (WorldNetDaily, 041224)

Forensic experts use computer images from Shroud of Turin to guess age 12

Computer-generated sketch of boy Jesus based on Shroud of Turin (courtesy Retequattro-Mediaset

What did Jesus Christ of Nazareth look like as a boy?

While no one knows for certain, forensic experts are now using computer images from the Shroud of Turin along with historical data and other ancient images to make an educated guess.

In a documentary called “Jesus’ Childhood” airing Sunday night on the Italian TV station Retequattro of the Mediaset Group, police artists use the same “aging” technology employed when searching for missing persons and criminals.

“In this case the experts went backwards. Now we have a hypothesis on how the man of the shroud might have looked at the age of 12,” Mediaset said in a statement. “While some features, such as the color of the eyes and the hair’s length, cut and color, are arbitrary, others come directly from the face impressed on the shroud.”

The group points out the facial proportions between the nose and eyebrow, as well as the shape of the jaw are identical to those on the shroud, which is a piece of linen some believe to be the actual burial cloth of Jesus after he was crucified.

The resulting image shows a fair-skinned child with blond, wavy hair and dark eyes.

“We made a rigorous effort based on the Shroud of Turin, but it’s clear that the data at our disposal were limited,” police official Carlo Bui told the Italian paper Corriere della Sera. “Let’s say we have made an excellent hypothesis.”

The Bible itself gives little information as to the specifics of what Jesus looked like during his ministry.

It does say he was a descendant of King David, who may have been fair-skinned with a reddish tint to his face and hair. The Old Testament notes David as a youth “was ruddy, and withal of a beautiful countenance, and goodly to look to.” (I Samuel 16:12)

Others have argued Jesus was more olive or dark-skinned being from the Middle East.

The book of Isaiah gives what many believe to be a prophecy about Jesus’ appearance as a human being, noting there wouldn’t be any features out of the ordinary:

“For he shall grow up before him as a tender plant, and as a root out of a dry ground: he hath no form nor comeliness; and when we shall see him, there is no beauty that we should desire him.” (Isaiah 53:2)

When asked by Discovery News about the latest computer-generated image, Prof. James Charlesworth, an expert on Jesus research and the Gospel of John at Princeton Theological Seminary, said, “Too many Christians look down the well of history, seeking to see Jesus’ face, and see the reflection of their own image. Those who follow Jesus find him attractive and thence always tend to portray him as a very attractive male, as in this new image.”

“It shows clearly an Aryan Jesus, just like the Nazis proclaimed. Jesus was a Jew, looked like a Jew, and followed Jewish customs,” he said.

As WorldNetDaily previously reported, the Shroud of Turin itself has been mired in controversy for centuries, with some maintaining the image on the linen is that of the crucified Jesus, while others reject it as an elaborate hoax.

In the 1980s, three international laboratories were selected to run the newly refined accelerated mass spectrometry (AMS) method of carbon dating on the shroud, to help determine its time of origin. The labs, including one at the University of Arizona at Tucson, all concurred the shroud was dated 1260-1390 AD.

But many have since questioned the reliability of the carbon-dating process which fixed that time period.

In 2000, millions of people turned out to view the controversial fabric during a rare public display.

The New Testament does refer to linens in connection with Jesus’ burial, recounted when Jesus’ disciples went to his tomb:

Peter therefore went forth, and that other disciple, and came to the sepulchre. So they ran both together: and the other disciple did outrun Peter, and came first to the sepulchre. And he stooping down, and looking in, saw the linen clothes lying; yet went he not in. Then cometh Simon Peter following him, and went into the sepulchre, and seeth the linen clothes lie, And the napkin, that was about his head, not lying with the linen clothes, but wrapped together in a place by itself. (John 20:3-7)

While some think the “napkin” that was on Jesus’ head casts doubt on the whole shroud theory, others believe it helps validate the shroud as authentic.

A relic called the Sudarium of Oviedo is claimed by some to be the actual cloth around Jesus’ head.

The cloth is impregnated with blood and lymph stains that match the blood type on the Shroud of Turin. The pattern and measurements of stains indicate the placement of the cloth over the face.

Juan Ignacio Moreno, a Spanish magistrate based in Burgos, Spain, asks a critical question:

“The scientific and medical studies on the Sudarium prove that it was the covering for the same man whose image is [on] the Shroud of Turin. We know that the Sudarium has been in Spain since the 600s. How, then, can the radio carbon dating claiming the shroud is only from the 13th century be accurate?”

==============================

Reading the Shroud of Turin: How in fact was Jesus Christ laid in his tomb? (National Review Online, 050324)

By Barbara M. Sullivan

EDITOR'S NOTE: This article first appeared in the July 20, 1973 issue of National Review, prior to the first major scientific examination as to whether the Shroud of Turin was indeed the burial cloth of Jesus. It was written by Barbara Sullivan, then a mother of six residing in Carmel, New York, and received major national attention. We are happy to republish Mrs. Sullivan’s article here this Holy Week. For images of the Shroud, please visit www.shroud.com.

During the Fall of 1973, the enigmatic Holy Shroud of Turin will be displayed publicly for the first time in forty years. More important, for the first time in history, it will then be presented to an international scientific commission for investigation. The authorization for an extensive examination was recently given by Pope Paul VI, the Archbishop of Turin, and the House of Savoy, which owns the mysterious burial garment.

We may soon know more surely whether the remarkable visage on the Shroud is, as many believe, that of Jesus Christ.

Astonishing as the claim may seem, there is strong inferential reason to think that, yes, the Shroud is authentic, and, yes, the face on the cloth shows us exactly what Christ looked like. A bit of history may be useful to most readers.

Spoil of War?

The modern history of the Shroud might be said to have begun on May 8, 1898, when Secondo Pia was permitted to photograph the Shroud for the first time while it was being exhibited at the Cathedral in Turin. Pia was flabbergasted to find that his glass-plate photographic negative was turning out in the developing bath to show, in fact, a photographic positive image. The Shroud itself had somehow been stained in such a way that the body imprint on the cloth was a negative. This feature alone would seem to rule out the claim that the Shroud is an ancient or medieval forgery. What artist, centuries before, would have fabricated details that could only be discerned with the help of a nineteenth-century invention? And the photographic process, subsequently confirmed by the photographs taken by G. Enrie in 1931, brought out a wealth of hitherto concealed details.

The Shroud, when photographed in 1898, had been in Turin over three hundred years, having been brought there from France by Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy in 1578. The House of Savoy obtained it in 1452 when Margaret de Charny presented it to the then Duke of Savoy who relinquished two castles in exchange. It was kept in the Sainte Chapelle of Chambéry, there to be partly burned by the melting silver reliquary in a fire on December 3, 1532. (Today, the scorch marks, water stains, and repair patches are quite obvious.) Margaret's grandfather, Geoffrey de Charny, had founded a collegiate church at Lirey in 1353 where the "true Burial Sheet of Christ" was exposed for veneration around 1357. But Geoffrey, who died in 1356, had never been very explicit about how he obtained it. (And as Werner Bulst S.J. wrote in 1957: " . . . the possibility of acquiring the Shroud by unethical methods . . . is not to be lightly rejected. It was a rather usual method of securing relics in the Middle Ages.")

Some 150 years earlier, the armies of the Fourth Crusade, well diverted from their original goal, seized Constantinople in 1204. After sacking the city without mercy, the fabulous treasures were divided with their financiers. According to a prearranged plan the Venetians would get half of the Crusaders' conquests. In this foray, Venice obtained not only a section of Constantinople, which included the church of St. Sophia, but more than enough to extend her commercial supremacy. Islam was not the hindrance to the profitable trade in the Near East; the Byzantine Empire was. A chronicler of that Crusade, Robert de Clari, is quoted as slating that in the imperial church, Our Lady Saint Mary of Blachernae, " . . . where was the shroud in which Our Lord was wrapped which was stretched straight up every Friday, so that one could well see on it the figure of Our Lord; nobody knew, neither Greek nor Frank, what became of this shroud when the town was taken."

Photographic Details

A figured shroud known in the East in 1204; a figured shroud known in the West by about 1357-a gap which has not yet been bridged. However, 1204-1357 is no definitive period of demarcation, for through and around this hiatus in history stream other trappings of civilization. Intermingled with art forms, varied traditions, customs, and rumor are extant documented references to the burial linens of the Passion. Two of the earlier ones are cited as being the testimony of Arculph, who claims to have kissed the "Lord's winding sheet" in Jerusalem around 640; and St. Braulio writes, in 631, that the Shroud was then a known relic.

But how was the image on the cloth, the remarkable detail of which showed up only when photographed at the end of the nineteenth century, actually produced centuries ago?

Intrigued by Pia's photographs, a French scientist named Paul Joseph Vignon developed a hypothesis that has commanded some widespread, though not universal, support. It is known that the normal Jewish burial service in the time of Jesus made use of myrrh and aloes, ground into a kind of paste, which impregnated the burial shroud. Vignon showed that this combination of chemicals produced a substance highly sensitive to urea. The human body exudes urea profusely upon death, and especially when death is accompanied by great suffering. In Vignon's theory, the exuded urea reacted upon the paste to produce discoloration of the cloth.

Since 1898, scholars have been investigating every detail of the Shroud as shown in numerous photographs. Dark stains, clearly visible, mark the crown of thorns — evidently more a cap-like affair than the more familiar circlet. The spear-thrust shows up as a lentil-shaped wound on the right side.

Interestingly, the Shroud shows that the nails went through the wrists, not the palms, according to another French scientist. Dr. Pierre Barbet, a surgeon who brought his expertise to bear on the Shroud, embodied his conclusions in a chilling study, A Doctor at Calvary, available now in paperback translation. Some of his points:

Experiments with cadavers showed that a body suspended with a nail through the palms will tear loose but that there is a narrow passage through the wrists (the carpal area) that would support body weight. No doubt, the Roman executioners were aware of this from their experience with crucifixion. Again, it was noticed that the hands on the Shroud appear to lack thumbs. Studies showed that when a nail was driven through that particular point in the wrist, the thumbs dropped inward upon the palm.

According to Barbet, the Shroud shows that prior to taking up the Cross, Jesus was subjected to two drastic forms of punishment. First, he was severely beaten with a stick about 1.75 inches in diameter. "Excoriations are to be found everywhere on the face, but especially on the right side." Barbet found "haematomas beneath the bleeding surfaces." The nose "is deformed by a fracture of the posterior of the cartilage." The marks show that the stick was "vigorously handled by an assailant standing on the right of Jesus."

After that, he was subjected to scourging by two men employing the well-known Roman "flagrum," a leather whip featuring small balls of metal or bone designed to tear the skin. Barbet finds more than fifty such strokes. "All the wounds have the same shape, like a little halter about three centimeters long. The two circles represent the balls of lead. . . . We may assume that during the scourging he was completely naked, for the halter-like wounds are to be seen all over the pelvic region, which would otherwise have been protected. . . . Finally, there must have been two executioners. It is possible they were not of the same height, for the obliqueness of the blows is not the same on each side."

Surgeon Barbet is especially vivid when he comes to the effect of those nails driven through the passage in the wrist, and so necessarily damaging the median nerves: "The median nerves are not merely the motor nerves, they are also the great sensory nerves. When they were injured and stretched out on the nails in those extended arms like the strings of a violin on their bridge, they must have caused the most horrible pain. Those who have seen, during the war, something of the wounds of the nervous trunks, know that it is one of the worst tortures imaginable.

The spear-thrust, according to Barbet, was a coup de grace required by law in this form of execution. But by that time Jesus had expired as the result of a tetanic contraction of the muscles that quickly reached the 'respiratory system. The "condemned man could only escape from asphyxia by straightening himself on the nail through the feet, in order to lessen the dragging of the body on the hands; each time that he wished to breathe more freely or to speak, he had to raise himself on this nail, thus bringing on further suffering." But such exertions, says Barbet, made the tetanic reaction inevitable, and, he concludes, Jesus died from asphyxia.

Evidence of Authenticity

Some have argued that, yes, indeed, the Shroud appears to depict a man who had been so executed, but, they object, could the portrait be that of some other unfortunate? After all, countless persons of all sorts were executed by crucifixion. The Shroud may well be ancient but why assume that the face is that of Jesus?

This line of argument is quite possibly mistaken. The body represented on the Shroud can have been wrapped in the garment only a few days at most, for normal decomposition would have destroyed the image. In the ancient world, the dead were not ordinarily disturbed, because the decomposing body was considered unclean.

Wherever you turn, the evidence argues for authenticity, often in quite unpredictable ways. It has long been observed, for example, that the physiognomy 'of Christ in portraits changed sharply around the year 300. But the new way of depicting him contains details which are apparently inexplicable such as a curious rectangular design over the nose, or a random spot of blood. We now see that these new features correspond to details on the Shroud. Perhaps the Shroud was taken from the original tomb to Rome, where during the period of persecution it was kept closely guarded by the Christian community. Only when the Christian church felt reasonably secure could the holy object be made available to pious artists: Hence, the sudden change in the style of depicting Christ in religious art.

What Do We See?

As we have noted, Pierre Barbet and other scholars have studied the Shroud for the light it sheds particularly on the events up to and including Jesus' death on the Cross. But can we press further? Can we use the Shroud to learn still more about those ancient events? We must be mindful, though, as Father Edward Wuenschel wrote in 1953, "of the sacredness of subject and the peculiar significance of every detail" and exercise "a wholesome restraint from theories that conflict with the imprints and with elementary scientific facts."

Can the Shroud, then, help us to dispel some of the obscuring mists of time? Perhaps a fundamental difficulty has been in the area of not so much what we have been looking at but, rather, how we have been looking. Perhaps, like the women from Galilee, we must follow after and behold the tomb, "and how his body was laid."

Yes, they saw how his body was laid. But what do we see?

What we visually perceive we consciously or subconsciously evaluate against that to which we are accustomed and to which we long have been exposed. Our exposure to death positions is a variable depending, for the most part, upon occupation and circumstances. Via our cultural heritage, we are accustomed to burials wherein the deceased are laid out flat. Regardless of any personal religious conviction, we also have been exposed to various artistic renderings of the crucified depicted as a standing-like or essentially elongated figure.

Indeed, we see the dorsal and frontal imprints on the Turin Shroud which give the illusion of an elongated figure. And, normally, we would expect a body to be laid out flat for burial. But is that the case with this particular relic?

Position of the Body

To establish a possible position of the body within the Shroud, the first thought is simply to place a fairly flexible photo-positive print of the overview on a flat surface and then bend the photo gently so that the top half (frontal image) is over the lower half (dorsal image). When we do this, the first thing we observe is that we are now unable to see the images; they are on the "inside." The top half is now upside down, or in actuality, right-side up. We must then try to appraise each view from the open sides to determine if we can fit them together. However, the body images are sort of wispy; there do not appear to be any clearly defined outlines. The dorsal imprint appears slightly longer than the frontal image, and there do not seem to be any obvious points or landmarks with which we can match the two surfaces.

With the overview again opened out on a flat surface, we very carefully scrutinize the photo. Starting in the center, a section separates the two portions of the head, the face and what appears to be the back of the head. Then there are the shoulder areas but, on the dorsal view, the left shoulder appears slightly higher than the right. The outer edges of the shoulders and the upper arms are obliterated by the scorch/burn marks and repair patches from the Chambéry fire. Both the chest area and the upper back show water stains, of unequal size. Next, on the top half, there are the forearms. No elbows are perceptible on the lower half. We note a band of staining that seems to extend beyond the right forearm, as a slight curve, which seems to include a good-sized "blob." Puzzling — because if this staining and "blob" beyond the right arm are drippage from that arm, then part of the top half of the cloth probably had been tucked under in some manner, because blood, or any other fluid, does not drip up.

No matter how careful we are, bending an opaque photo, however flexible, still leaves us on the "outside." But when we take some tracing paper, sketch what we can of this area, and bend the tracing, we are able to simulate a possible fabric tuck-in. This leads us to consider whether other areas had been tucked in and around the body. Might it be possible that in the myriad details there is evidence that would relate to actual body-surface curvatures? Could we even begin to approximate the position of the body that was once within the Shroud of Turin?

The Transparency Factor

Our initial attempts are made with tracings on a 22-inch overview of the photo-positive (a 1:7.5 reproduction). In addition to the advantage of a "transparency" factor, we are able arbitrarily but cautiously to exclude the burn/scorch marks, water stains, and repair patches, collectively referred to as the Chambéry data. These details, in themselves, are quite distracting and because this extensive damage occurred at a known point in time, 1532, it is self-evident that it does not relate to the earlier history of the Shroud. (There are sets of smaller burn marks of unknown cause and date, which were depicted on a painted copy of the Shroud dating from 1516.)

Recalling that the opacity of the photo itself was a hindrance in our attempt to align the back and front images, we make a tracing of the overview, on which we lightly pencil sketch as much of the body as possible, eliminating the Chambéry data. Because of the "transparency" of the tracing paper, we are able to use different colored pens to emphasize pertinent details — the head images, shoulder lines, left wrist wound, and feet. We include some of the obvious crease lines over and just peripheral to the image areas. We must also trace each end of the Shroud visible in the photo, not the ends of the photo itself, and cut out our overview along these lines.

We then overlap the tracing as we had tried to do with the photo, bringing the end of the top half to the end of the lower half. When we do this, two things seem to happen: 1) The tracing bends more in the area of the head, back image, than in the "water-stained" space between the two sections; 2) the tracing of the "isolated" foot imprint at the end of the top half does not seem to "match" with the imprint of the right foot on the lower half. To explain it differently, the imprint of the right foot appears as if it is slanted inward. The foot image from the top half does not appear to line, up in the same direction.

Separate tracings of both the upper and lower sections, with just the feet detail, are made and then placed end to end on a flat surface. What we see is that the foot imprint, top half, seems to line up in a direction quite similar to that of the partial imprint of the left foot, lower half.

And we ask ourselves: Do we see what we see, or are we just imagining the whole thing because this approximate relationship is a contrast to the supposition of other researchers, namely that the imprint, top half, resulted from the fabric having been draped over the toes of the right foot.

But, we are not imagining. Copies of sections of the photo-overview (carefully made for this research only) are used to simulate the same maneuver. By end-to-end matching of these sectional photocopies, the same results can be demonstrated. However, photos, photo-tracings, or photocopies are one-dimensional. We have to account for three dimensions. The frontal and dorsal images give us basically two surfaces; is there evidence for the third — depth? Here, we start to incorporate the wrinkles and creases.

In addition to the various wrinkles and creases around the foot imprint, top half, there are others that traverse this area as curved lines, particularly through the midsection. So we trace as many of these as we can, ink them lightly, and then "pinch" the paper along the traced lines. What happens is that the paper crinkles or buckles in such a manner that the area corresponding to the stained end of the Shroud "shortens" in its center portion and the outer parts seem to be more "tapered." The whole thing has a gently curved appearance and we seem to have produced part of a sole of a foot and a portion of the sides.

When we overlay this pinched-together formation on the dorsal half, the buckled lower edge from the top half seems to fit or align more closely with the somewhat diagonally curved tracing of the partial imprint of the left foot. Of course, we try the end-to-end matching as we did earlier but this time we match the end of the top half-tracing with the lower half-photo. Again, the top foot imprint tracing orients more to the left foot on the lower half of the photo.

Some Conclusions

However, there are several things we observe as we do this simulated overlap of the top half and possible left foot alignment: 1) We seem to have approximated the envelopment of the left foot but not the right foot; 2) the dimensional matching is rather difficult because the image tracings are still completely on the "inside"; 3) visualization from "outside" is enhanced only where the image-tracings have been inked; 4) the dorsal image appears to lift or curve upward more in the area of the neck and shoulders; 5) the frontal image seems to shorten.

It is imperative that we describe these observations of the empirical image matching as approximations because our tracings are based on a small-scale photo. However, we still have some latitude in which to explore various relationships. Although time- consuming, perhaps tedious, we are able to make additional sectional or working tracings and continue our trial-and-error attempts.

Since we have a possible completion of the left foot and observe that this is positioned somewhat over the area of the right foot, we again have to ac- count for depth. This leads us to consider that the space between the foot imprints on the dorsal half might be an "elevation" rather than a gap between the two feet on a horizontal plane. Our separate tracing of this section gives us a degree of flexibility to try to experiment with this dimensional effect. When we repeat it on the main tracing, overlap and align the left foot imprints, we now have a somewhat closer fit, with the left well across the right. This, however, seems to sort of shift or slightly twist the major portion of the frontal image to the right, the space between the two head sections seems to lift a bit more, and the back image now bends in the area of the shoulders.

Our attempts to develop the possible curves of the right foot are indeed a challenge, and incomplete. Here, we seem to have to find simultaneously the position of the legs, and to account for the stained section along the end of the dorsal half.

We also make an effort to align the head images. The one thing we find here is that these will not "match up" on a midline relationship. We get a partial dimensional projection when we consider that the "unstained" appearing space between the hair and the face might be an outward tuck-folding over the face, and pinch the tracing to show this. We also explore the possibility that the gaps or interruptions in the head image, back portion, might be dart-like patterns. When we "triangulate" these imprints and butt or match the perceptible edges, the result is the beginning of a cap-like configuration. However, the intervening space between the two partially dimensionalized images gets in the way somewhat, and it is difficult, with this small-scale tracing, to fit these two sections together to determine the crown of the head.

Other areas of body relationships are studied, as well as attempts made to accommodate the extra portions of the fabric-tracing beyond the image areas. These, though not yet completed, would require a prolonged description at this time. In presenting an approximate completion of the left foot, we at least demonstrate that out of the myriad of Shroud details, some of the wrinkles and creases relate to actual body-surface curvature. We also find evidence to indicate that: 1) The left foot possibly situates well across the right foot; 2) the frontal image "shortens," with a twist or shift to the right; 3) there is a marked curvature of the dorsal image that, so far, involves the head, neck, and shoulder areas. However preliminary these data, they do seem to suggest that the image is somewhat hunched and lies to one side.

Factual Basis

All of the possible dimensional projections are tentative and must be either substantiated or ruled out by similar tracings on large-scale photos. At some point in time a fabric pattern could be made, incorporating whatever data have been found to be pertinent. To work with life-size photographs or a photographic print on pliable cloth would be ideal; the latter, though, would still have the distracting detail of the Chambéry damage — and air-brushing is a costly technique.

A refolding of the Shroud itself would seem to be a most logical thing to do. However, without a pattern or plan of possibilities, a direct dimensional study on an object as opaque as the Shroud would be blind, cumbersome, and require an undue amount of manipulation of the fabric. It must also be considered whether or not the existence and location of the repair patches might actually hinder, if not preclude, any attempt to do such a critical direct dimensionalization — and this is assuming total removal of the backing material. The image, however well aligned, would still be on the inside.

We have not gone on a flight of fancy, nor have we overprojected our imagination. We have a basis in fact: photographs of the Shroud of Turin; from these we have started to establish an analogy by which we will be able to envision the burial of the crucified body.

What did the women see when they "beheld the tomb and how his body was laid"? We are just beginning to look over their shoulders.

==============================

Scientists errred in Turin relic tests, author says (Ottawa Citizen, 990314)

A book to be released in Canada this coming week suggests the Shroud of Turin contains the DNA of God, as well as microscopic splinters from the cross used in the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

The shroud has been labelled by scientists and theologians as everything from a brilliant hoax to proof positive of the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ. Dr. Leoncio Garza‑Valdes, a devout Catholic, is the latest in a long string of authors who claim to have found new evidence that suggests the shroud really is the burial cloth of Jesus.

In his book The DNA of God?, he argues that scientists in Britain, the United States and Switzerland erred when they carried out carbon‑dating tests on the shroud in 1988 and concluded the four‑metre‑long cloth actually dates from the 13th or 14th century instead of from 30 A.D.

Dr. Garza‑Valdes, a microbiologist, amateur archeologist and physician, says that what earlier scientists have neglected is what he calls a bioplastic coating, much like plaque on teeth, that has been formed over the centuries by bacteria on the shroud.

He says tests he carried out on Egyptian mummies and Mayan jade artifacts, as well as samples from the shroud, show this barely perceptible coating distorts the carbon‑dating of ancient artifacts that have been left undisturbed for long periods.

Dr. Garza‑Valdes says he has put a question mark on the title of his book ‑‑ The DNA of God? ‑‑ because there is no way to be certain the crucified man whose photographic‑like image appears on the shroud is actually Jesus.

“But at this moment, I have not found any reason he cannot be Jesus. And if it is Jesus ‑‑ and if you are a Christian ‑‑ the DNA I found is that of God the Son,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Garza‑Valdes says, however, there is no fear Jesus can be cloned. The DNA samples he found, taken from the shroud, are not complete enough to be replicated, he said.

He says along with the DNA, he also found traces of microscopic splinters of oak and what might have been the vinegar offered to Jesus on a sponge at the Cross.

The Shroud of Turin has been venerated by Catholics as the burial cloth of Christ since at least 1357, and attracted about two million visitors, including Pope John Paul II, when it was displayed last year at the Turin Cathedral in Italy. Officially, however, the Catholic church says only that the cloth is an important relic symbolizing the suffering of Jesus.

The image on the cloth was fully revealed only in 1898, when a photographer took the first photo of the indistinct markings. In the darkroom, the photographic negative revealed the long, thin face of a man with long hair, a mustache and a beard.

No one has come up with a definitive explanation for the full‑length image of a man who has been scourged, beaten and crucified. Some have suggested the image was flashed onto the cloth in a burst of radiant energy, while others say it was produced by a primitive form of photography or a clever artist.

Art experts say this is unlikely because photographic techniques were almost certainly unknown in the 14th century, and no artist of the time had the skills to paint a human figure that would show up only 500 or more years later on a photographic negative.

Dr. Garza‑Valdes says his tests show the image is that of a first‑century Jew with type AB blood, a blood type relatively rare in the general population but common among Jews.

Pathologists and others have examined the image and report puncture wounds on the back of the head consistent with a crown of thorns, as well as scourge marks inflicted by two men using whips with pieces of metal or bone on the end of the thongs.

Other marks indicate the man was nailed to the cross by his wrists and feet and stabbed in the side after death.

Dr. Garza‑Valdes says although many Jews were crucified in Palestine in the first century, there could not have been many who bore the marks of all the wounds the New Testament suggests were inflicted on Christ.

Barrie M. Schwortz, The Associated Press / Evidence of the authenticity of the four‑metre Shroud of Turin, venerated by some as the burial cloth of Jesus, became stronger when a team from the University of Texas reported the cloth is indeed old enough to have been used for that purpose.

==============================