Church News

Theology: General News

>> = Important Articles; ** = Major Articles

>>A Call for Theological Triage and Christian Maturity (Christian Post, 050713)

>>Universalism: Truth in Labeling—The Audacity of Heresy (Christian Post, 050111)

>>Must We Believe the Virgin Birth? (Christian Post, 041224)

**In the Shadow of Death—The Little Ones Are Safe With Jesus (Christian Post, 050108)

**The Doctrine of the Virgin Birth Under Attack—Again (Christian Post, 041224)

**It Takes One to Know One—Liberalism as Atheism (Christian Post, 041124)

Pope: God will never destroy world again (970216)

St Paul’s finds modern creed is beyond belief (970924)

Last Supper clues challenge Easter week timetable (970407)

Church’s liturgy to include exorcism and healing (980615)

Many Americans still wonder about the nature of Jesus (Star Tribune, 040104)

The ‘Openness of God’ and the Future of Evangelical Theology (Christian News, 041119)

The Faith vs. the Force: The Mythology of ‘Star Wars’ (Christian News, 041119)

Intellectual or Religious? Kristof Requires a Choice (Christian Post, 041224)

TIME Lists America’s 25 Most Influential Evangelicals (Christian Post, 050201)

Marian Dogma and the Anglican Conundrum (Christian Post, 050524)

‘A Generous Orthodoxy’—Is It Orthodox? (Christian Post, 050621)

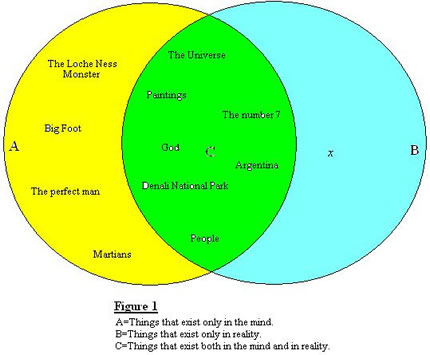

Anselm’s Ontological Argument (trueU.org, 050818)

Theological Education That Transforms, Part 1 (Christian Post, 051202)

Theological Education That Transforms, Part 2 (Christian Post, 051205)

Socrates’ Proof for The Existence Of A Deity.

THEOLOGY: Can Believers Be Bible Scholars? A Strange Debate in the Academy (Mohler, 060320)

CHURCH: The Pastor As Theologian, Part One—The Pastor’s Calling (Mohler, 060417)

CHURCH: The Pastor As Theologian, Part 2—The Pastor’s Concentration (Mohler, 060419)

CHURCH: The Pastor As Theologian, Part 3—The Pastor’s Conviction and Confession (Mohler, 060421)

Pacific Churches Urged to Bring ‘Coconut Theology’ to Global Platform (Christian Post, 070906)

Between Two Extremes: Liberalism and Fundamentalism (Christian Post, 070924)

==============================

>>A Call for Theological Triage and Christian Maturity (Christian Post, 050713)

In every generation, the church is commanded to “contend for the faith once for all delivered to the saints.” That is no easy task, and it is complicated by the multiple attacks upon Christian truth that mark our contemporary age. Assaults upon the Christian faith are no longer directed only at isolated doctrines. The entire structure of Christian truth is now under attack by those who would subvert Christianity’s theological integrity.

Today’s Christian faces the daunting task of strategizing which Christian doctrines and theological issues are to be given highest priority in terms of our contemporary context. This applies both to the public defense of Christianity in face of the secular challenge and the internal responsibility of dealing with doctrinal disagreements. Neither is an easy task, but theological seriousness and maturity demand that we consider doctrinal issues in terms of their relative importance. God’s truth is to be defended at every point and in every detail, but responsible Christians must determine which issues deserve first-rank attention in a time of theological crisis.

A trip to the local hospital Emergency Room some years ago alerted me to an intellectual tool that is most helpful in fulfilling our theological responsibility. In recent years, emergency medical personnel have practiced a discipline known as triage—a process that allows trained personnel to make a quick evaluation of relative medical urgency. Given the chaos of an Emergency Room reception area, someone must be armed with the medical expertise to make an immediate determination of medical priority. Which patients should be rushed into surgery? Which patients can wait for a less urgent examination? Medical personnel cannot flinch from asking these questions, and from taking responsibility to give the patients with the most critical needs top priority in terms of treatment.

The word triage comes from the French word trier, which means “to sort.” Thus, the triage officer in the medical context is the front-line agent for deciding which patients need the most urgent treatment. Without such a process, the scraped knee would receive the same urgency of consideration as a gunshot wound to the chest. The same discipline that brings order to the hectic arena of the Emergency Room can also offer great assistance to Christians defending truth in the present age.

A discipline of theological triage would require Christians to determine a scale of theological urgency that would correspond to the medical world’s framework for medical priority. With this in mind, I would suggest three different levels of theological urgency, each corresponding to a set of issues and theological priorities found in current doctrinal debates.

First-level theological issues would include those doctrines most central and essential to the Christian faith. Included among these most crucial doctrines would be doctrines such as the Trinity, the full deity and humanity of Jesus Christ, justification by faith, and the authority of Scripture.

In the earliest centuries of the Christian movement, heretics directed their most dangerous attacks upon the church’s understanding of who Jesus is, and in what sense He is the very Son of God. Other crucial debates concerned the question of how the Son is related to the Father and the Holy Spirit. The earliest creeds and councils of the church were, in essence, emergency measures taken to protect the central core of Christian doctrine. At historic turning-points such as the councils at Nicaea, Constantinople, and Chalcedon, orthodoxy was vindicated and heresy was condemned—and these councils dealt with doctrines of unquestionable first-order importance. Christianity stands or falls on the affirmation that Jesus Christ is fully man and fully God.

The church quickly moved to affirm that the full deity and full humanity of Jesus Christ are absolutely necessary to the Christian faith. Any denial of what has become known as Nicaean-Chalcedonian Christology is, by definition, condemned as a heresy. The essential truths of the incarnation include the death, burial, and bodily resurrection of the Lord Jesus Christ. Those who deny these revealed truths are, by definition, not Christians.

The same is true with the doctrine of the Trinity. The early church clarified and codified its understanding of the one true and living God by affirming the full deity of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit—while insisting that the Bible reveals one God in three persons.

In addition to the Christological and Trinitarian doctrines, the doctrine of justification by faith must also be included among these first-order truths. Without this doctrine, we are left with a denial of the Gospel itself, and salvation is transformed into some structure of human righteousness. The truthfulness and authority of the Holy Scriptures must also rank as a first-order doctrine, for without an affirmation of the Bible as the very Word of God, we are left without any adequate authority for distinguishing truth from error.

These first-order doctrines represent the most fundamental truths of the Christian faith, and a denial of these doctrines represents nothing less than an eventual denial of Christianity itself.

The set of second-order doctrines is distinguished from the first-order set by the fact that believing Christians may disagree on the second-order issues, though this disagreement will create significant boundaries between believers. When Christians organize themselves into congregations and denominational forms, these boundaries become evident.

Second-order issues would include the meaning and mode of baptism. Baptists and Presbyterians, for example, fervently disagree over the most basic understanding of Christian baptism. The practice of infant baptism is inconceivable to the Baptist mind, while Presbyterians trace infant baptism to their most basic understanding of the covenant. Standing together on the first-order doctrines, Baptists and Presbyterians eagerly recognize each other as believing Christians, but recognize that disagreement on issues of this importance will prevent fellowship within the same congregation or denomination.

Christians across a vast denominational range can stand together on the first-order doctrines and recognize each other as authentic Christians, while understanding that the existence of second-order disagreements prevents the closeness of fellowship we would otherwise enjoy. A church either will recognize infant baptism, or it will not. That choice immediately creates a second-order conflict with those who take the other position by conviction.

In recent years, the issue of women serving as pastors has emerged as another second-order issue. Again, a church or denomination either will ordain women to the pastorate, or it will not. Second-order issues resist easy settlement by those who would prefer an either/or approach. Many of the most heated disagreements among serious believers take place at the second-order level, for these issues frame our understanding of the church and its ordering by the Word of God.

Third-order issues are doctrines over which Christians may disagree and remain in close fellowship, even within local congregations. I would put most of the debates over eschatology, for example, in this category. Christians who affirm the bodily, historical, and victorious return of the Lord Jesus Christ may differ over timetable and sequence without rupturing the fellowship of the church. Christians may find themselves in disagreement over any number of issues related to the interpretation of difficult texts or the understanding of matters of common disagreement. Nevertheless, standing together on issues of more urgent importance, believers are able to accept one another without compromise when third-order issues are in question.

A structure of theological triage does not imply that Christians may take any biblical truth with less than full seriousness. We are charged to embrace and to teach the comprehensive truthfulness of the Christian faith as revealed in the Holy Scriptures. There are no insignificant doctrines revealed in the Bible, but there is an essential foundation of truth that undergirds the entire system of biblical truth.

This structure of theological triage may also help to explain how confusion can often occur in the midst of doctrinal debate. If the relative urgency of these truths is not taken into account, the debate can quickly become unhelpful. The error of theological liberalism is evident in a basic disrespect for biblical authority and the church’s treasury of truth. The mark of true liberalism is the refusal to admit that first-order theological issues even exist. Liberals treat first-order doctrines as if they were merely third-order in importance, and doctrinal ambiguity is the inevitable result.

Fundamentalism, on the other hand, tends toward the opposite error. The misjudgment of true fundamentalism is the belief that all disagreements concern first-order doctrines. Thus, third-order issues are raised to a first-order importance, and Christians are wrongly and harmfully divided.

Living in an age of widespread doctrinal denial and intense theological confusion, thinking Christians must rise to the challenge of Christian maturity, even in the midst of a theological emergency. We must sort the issues with a trained mind and a humble heart, in order to protect what the Apostle Paul called the “treasure” that has been entrusted to us. Given the urgency of this challenge, a lesson from the Emergency Room just might help.

____________________________________________________

R. Albert Mohler, Jr. is president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky.

==============================

>>Universalism: Truth in Labeling—The Audacity of Heresy (Christian Post, 050111)

Philip Gulley and James Mulholland are at it again. In 2003, the duo released If Grace Is True: Why God Will Save Every Person, and the book quickly found its way to major trade bookstores and entered the publicity cycle.

Now, Gulley and Mulholland have written If God Is Love: Rediscovering Grace in an Ungracious World, and the new book is presented as the next chapter in their unfolding account of their evolving theology. Make no mistake—these authors intend to remake Christianity in their own image. In If Grace Is True, the authors presented a glittering and glandular argument for the heresy of universalism—the claim that all persons will eventually be saved because God will not send anyone to Hell. Their approach was cleverly packaged and presented in simple language. They simply rejected one of Christianity’s most central teachings and replaced it with something far more attractive to postmodern Americans. At the affective and emotional levels, the authors urged their readers to shift toward a view of God that was more emotionally satisfying in terms of contemporary concepts of acceptance and love. The deity they present is infinitely nonjudgmental, eternally tolerant, and bears virtually no resemblance to the God of the Bible. That doesn’t stop them from claiming that their new theology is just Christianity reformed. This is a free country, and citizens are free to establish whatever religion they may wish and devise. From Mary Baker Eddy and Joseph Smith to Reverend Moon and Deepak Chopra, Americans—native and naturalized—have been inventing new religions as a national pastime. America has become a marketplace of religious confusions and competing spiritualities. Start a new religion if you are so inclined—just have the integrity not to call what you devise “Christianity.”

In the first book, Gulley and Mulholland jettisoned the entire structure of Christian conviction. Sin makes no sense in a theological structure that excludes judgment. God must be reconceived so that He is no longer a God of justice concerned with righteousness but is instead an agent of personal transformation among His human creatures, calling out the very best in every person and every situation. No one is beyond His salvific purpose, and even Satan will eventually be reconciled to God and will take his place in the great harmonic age to come.

Salvation must be reconceptualized so as to remove any atoning work accomplished by Jesus Christ and reduce the entire scheme of salvation to something like a self-help program that produces and evolves spiritual consciousness.

As I mentioned in my review of If Grace Is True, the authors are to be congratulated at at least one point. They do admit that their reformulation of Christianity requires that the Bible be discarded as an infallible and authoritative guide. In arguing for a universal salvation, the Bible is an insurmountable obstacle. Can a Christian believe that God will save everyone? “Obviously, if a Christian must believe that the Bible is the ‘infallible words of God,’ the answer is no. There are too many verses about judgment, Hell, and the eternal punishment of the wicked to make such optimism reasonable.”

The authors press their argument to a new level in If God Is Love, now arguing that Christianity must be transformed from a religion of fear and reward to a “gracious” faith of unconditional acceptance. They urge the church to move from a “theology of fear” to a “theology of grace” that would completely transform Christianity, the church, and religion itself.

As in their first book, the authors write in the singular first person, combining their personal and autobiographical references into one voice. This is a bit eccentric, to say the least, and it makes for an awkward reading experience. Nevertheless, these authors do get their argument across, and in less than subtle terms.

They begin by relating an account of an experience one of the authors endured as pastor of a small congregation. Asked by an elderly woman if he believed in Satan and Hell, the pastor, “eager to prove my theological sophistication,” told her that he did not believe in Satan nor “in a place where people were endlessly tormented.” As he explains, “This was before I learned that answering theological questions directly and honestly is generally a bad idea, and that ministers go to seminary precisely so we can master the theological language necessary to bewilder people when pressed to provide answers they might not like.” That indictment certainly fits some theological seminaries, who train their graduates to speak in theological “double-speak” that sounds conservative but masks a subterfuge of the faith.

Ejected from that pulpit, the pastor quickly found himself in a new church where his liberal theology was much more appreciated. For the remainder of the book, the authors flesh out what this liberal “gracious” religion would look like, and they try to present their product as a reformulated version of Christianity.

The heart of their argument is that classical, biblical Christianity is a “dualistic” theology. Accordingly, “everyone is either under divine control (saved) or in rebellion (unsaved).” Such a dualistic understanding requires the existence of both Heaven and Hell, and generally results in hierarchical systems of religious authority that “see God as severe, rigid, judgmental, intolerant, jealous, and condemning.” As they explain, “The problem with dualistic theologies is that God’s desire is to separate the wheat from the chaff, the sheep from the goats, the saved from the damned.”

Gulley and Mulholland admit that the Bible is filled with such dualistic teaching and that traditional Christianity has recognized this as the very structure of the faith. Nevertheless, they reject classical Christianity as an intolerant faith that simply does not fit the needs of modern times. In their first book, they argued for the principle of universal salvation. In this second book, they sketch out what shape this new form of Christianity would take, and how it would be applied to many areas of life.

Turning from fear to grace would mean, they argue, leaving behind outdated concepts of sin and God’s judgment. Fear would be replaced with an unconditional acceptance of our acceptance by God. They look back at the Gospel as it was taught to them as children and remember, “every Sunday we were reminded of how Jesus paid it all, how He loved us so much He died for us. The descriptions of His crucifixion were not of a religious reformer killed by the authorities, but of a friend laying down His life for us.” They now see this understanding of Jesus’ life and death as unhealthy, both mentally and spiritually.

When they discuss moving from a “theology of fear” to a theology of grace, they mean abandoning the very structure of reward and punishment, divine justice and atonement, and, of course, the idea of Hell. “Human transformation comes when love casts out fear,” they argue, “assuring us we’ll never be disowned, abandoned, or destroyed. Only in the rich soil of unconditional love can we truly grow. Believing in God’s desire to save every person calms our fears of death and destruction. It assures us of God’s acceptance. Grace gives us the freedom to live boldly.”

Since fear and love are “incompatible,” according to these authors, fear must be discarded as an inappropriate impulse. Even though Jesus warned that we should fear Hell and the wrath of God, these authors simply pick and choose among biblical passages to find a foundation for redefining the faith.

But, if fear of Hell is an inadequate concern for their new religion, so is the hope of Heaven. “Religion focused on escaping hell’s flames is ugly, but appeals based on entering heaven’s gates are equally flawed,” they assert. In other words, we should not love and obey God out of hope of Heaven, but simply for what will come to us in this world through reaching harmony and satisfaction here on earth. “If fear-based theology justifies a God who can be abusive, reward-earning theology creates religious gold diggers—people in relationship for the wrong reasons. Belonging in God’s desire to save every person challenged my need to compete with sinners for some heavenly prize. It allowed me to approach God with gratitude rather than greed. Grace allowed me to move beyond punishment and reward.”

Throughout the book, the authors provide ample evidence of what it takes to transform Christianity into a structure more to their liking. They are honest in rejecting the truthfulness of many biblical passages. Discussing the death of Uzzah as recorded in 2 Samuel 6:7, they acknowledge that the Bible claims that the Lord killed Uzzah because he violated the command not to touch the Ark of the Covenant. This passage reveals a God that punishes wrongdoing, the authors acknowledge. Nevertheless, “I don’t believe that story any longer. I am convinced our heavenly Parent not only expects our indiscretions, but sees them as opportunities not to destroy us, but to encourage and teach us.”

In a similar vein, the authors reject the truthfulness of Ephesians 5:22-23, acknowledging that this passage affirms the authority of husbands in marriage. “Unfortunately, such scriptures, rather than reflecting God’s hope for relationships, reflect the influence of a patriarchal and hierarchical society in which power and control rather than grace held sway.”

In If God Is Love, the authors present a complete rejection of classical Christianity and put in its place a postmodern mixture of wishful thinking and theological invention. In their view of a “gracious life,” religion would lead all persons to reject patterns of hierarchical authority, move into an unprecedented age of cooperation and “graciousness,” and recognize that all human beings share the same basic concerns and are assured of the same eventual destiny.

Accordingly, the church of this new religion would reject pastoral authority and would take as its message the universal love of God applied to everyday life. The authors are clearly concerned with maintaining some form and structure of morality, but they offer no insight into how human beings are even to understand what morality would require. In such a structure, where do we gain any understanding of right and wrong?

Interestingly, the authors are unwilling to dispense with these categories altogether. They are certain that the death penalty is wrong and that the church must move to embrace same-gender marriage. Nevertheless, they concede that abortion “is often an ungracious act.” Not that they want to ban abortion altogether, they simply want a world in which abortion would be rare “and always the lesser of two evils.”

Even though this new book is largely a rehash of arguments already presented in If Grace Is True, If God Is Love does take the reader into new territory. The authors offer various insights on matters ranging from economics to international politics and the roots of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

They do not underestimate the revolutionary character of their arguments. “Becoming gracious will require a reformation that will make Luther’s look like redecorating. It will require us to abandon our claim to be favored children. We’ll have to surrender the Bible as our ace in the hole and Jesus as a backstage pass. The Church will have to serve, rather than dominate, the world. Christianity will need to reclaim its most distinctive doctrine—the universal grace of God. Hell and damnation will no longer be tools of the trade. We’ll need to identify Christians not by what they believe about Jesus, but by their willingness to be like Him.”

Gulley and Mulholland acknowledge that not all will receive their message with acceptance [they even acknowledge my criticism of If Grace Is True, commenting, “Not everyone is a fan.”].

These authors have obviously tapped into popular interest and the desire of many postmodern persons to find any spiritual substitute for authentic Christianity. They have every right to devise their own religion and come up with whatever structure of theology and belief they would offer. They have every right to present their case before the world, to organize their own congregations and institutions, ordain their own clergy (if any), and call for converts.

Nevertheless, those who would redefine Christianity and eviscerate the central doctrines of the faith should at least have sufficient integrity not to call their new product Christianity. Liberated from concern for biblical authority, Gulley and Mulholland simply pick and choose among biblical texts, constructing a concept of Jesus that fits their new religion. This has been tried before, and it will be tried again.

Grace is indeed true and God is indeed love, but what Gulley and Mulholland present in these books is simply not Christianity.

___________________________________________

R. Albert Mohler, Jr. is president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky.

==============================

>>Must We Believe the Virgin Birth? (Christian Post, 041224)

[KH: Conservative thologians believe that virgin birth is a good test stone for orthodoxy.]

In his recent column in The New York Times, Nicholas Kristof pointed to belief in the Virgin Birth as evidence that conservative Christians are “less intellectual.” [see this week’s WebLog entries] Are we saddled with an untenable doctrine? Is belief in the Virgin Birth really necessary?

Kristof is absolutely aghast that so many Americans believe in the Virgin Birth. “The faith in the Virgin Birth reflects the way American Christianity is becoming less intellectual and more mystical over time,” he explains, and the percentage of Americans who believe in the Virgin Birth “actually rose five points in the latest poll.” Yikes! Is this evidence of secular backsliding?

“The Virgin Mary is an interesting prism through which to examine America’s emphasis on faith,” Kristof argues, “because most Biblical scholars regard the evidence for the Virgin Birth ... as so shaky that it pretty much has to be a leap of faith.” [see Kristof article] Here’s a little hint: Anytime you hear a claim about what “most Biblical scholars” believe, check on just who these illustrious scholars really are. In Kristof’s case, he is only concerned about liberal scholars like Hans Kung, whose credentials as a Catholic theologian were revoked by the Vatican.

The list of what Hans Kung does not believe would fill a book [just look at his books!], and citing him as an authority in this area betrays Kristof’s determination to stack the evidence, or his utter ignorance that many theologians and biblical scholars vehemently disagree with Kung. Kung is the anti-Catholic’s favorite Catholic, and that is the real reason he is so loved by the liberal media.

Kristof also cites “the great Yale historian and theologian” Jaroslav Pelikan as an authority against the Virgin Birth, but this is both unfair and untenable. In Mary Through the Centuries, Pelikan does not reject the Virgin Birth, but does trace the development of the doctrine.

What are we to do with the Virgin Birth? The doctrine was among the first to be questioned and then rejected after the rise of historical criticism and the undermining of biblical authority that inevitably follwed. Critics claimed that since the doctrine is taught in “only” two of the four Gospels, it must be elective. The Apostle Paul, they argued, did not mention it in his sermons in Acts, so he must not have believed it. Besides, the liberal critics argued, the doctrine is just so supernatural. Modern heretics like retired Episcopal bishop John Shelby Spong argue that the doctrine was just evidence of the early church’s over-claiming of Christ’s deity. It is, Spong tells us, the “entrance myth” to go with the resurrection, the “exit myth.” If only Spong were a myth.

Now, even some revisionist evangelicals claim that belief in the Virgin Birth is unnecessary. The meaning of the miracle is enduring, they argue, but the historical truth of the doctrine is not really important.

Must one believe in the Virgin Birth to be a Christian? This is not a hard question to answer. It is conceivable that someone might come to Christ and trust Christ as Savior without yet learning that the Bible teaches that Jesus was born of a virgin. A new believer is not yet aware of the full structure of Christian truth. The real question is this: Can a Christian, once aware of the Bible’s teaching, reject the Virgin Birth? The answer must be no.

Nicholas Kristof pointed to his grandfather as a “devout” Presbyterian elder who believed that the Virgin Birth is a “pious legend.” Follow his example, Kristof encourages, and join the modern age. But we must face the hard fact that Kristof’s grandfather denied the faith. This is a very strange and perverse definition of “devout.”

Matthew tells us that before Mary and Joseph “came together,” Mary “was found to be with child by the Holy Spirit.” [Matthew 1:18] This, Matthew explains, fulfilled what Isaiah promised: “Behold, the virgin shall be with child and shall bear a Son, and they shall call His name ‘Immanuel,’ which translated means ‘God with Us’.” [Matthew 1:23, Isaiah 9:6-7]

Luke provides even greater detail, revealing that Mary was visited by an angel who explained that she, though a virgin, would bear the divine child: “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; and for that reason the holy child shall be called the Son of God.” [Luke 1:35]

Even if the Virgin Birth was taught by only one biblical passage, that would be sufficient to obligate all Christians to the belief. We have no right to weigh the relative truthfulness of biblical teachings by their repetition in Scripture. We cannot claim to believe that the Bible is the Word of God and then turn around and cast suspicion on its teaching.

Millard Erickson states this well: “If we do not hold to the virgin birth despite the fact that the Bible asserts it, then we have compromised the authority of the Bible and there is in principle no reason why we should hold to its other teachings. Thus, rejecting the virgin birth has implications reaching far beyond the doctrine itself.”

Implications, indeed. If Jesus was not born of a virgin, who was His father? There is no answer that will leave the Gospel intact. The Virgin Birth explains how Christ could be both God and man, how He was without sin, and that the entire work of salvation is God’s gracious act. If Jesus was not born of a virgin, He had a human father. If Jesus was not born of a virgin, the Bible teaches a lie.

Carl F. H. Henry, the dean of evangelical theologians, argues that the Virgin Birth is the “essential, historical indication of the Incarnation, bearing not only an analogy to the divine and human natures of the Incarnate, but also bringing out the nature, purpose, and bearing of this work of God to salvation.” Well said, and well believed.

Nicholas Kristof and his secularist friends may find belief in the Virgin Birth to be evidence of intellectual backwardness among American Christians. But this is the faith of the Church, established in God’s perfect Word, and cherished by the true Church throughout the ages. Kristof’s grandfather, we are told, believed that the Virgin Birth is a “pious legend.” The fact that he could hold such beliefs and serve as an elder in his church is evidence of that church’s doctrinal and spiritual laxity — or worse. Those who deny the Virgin Birth affirm other doctrines only by force of whim, for they have already surrendered the authority of Scripture. They have undermined Christ’s nature and nullified the incarnation.

This much we know: All those who find salvation will be saved by the atoning work of Jesus the Christ — the virgin-born Savior. Anything less than this is just not Christianity, whatever it may call itself. A true Christian will not deny the Virgin Birth.

______________________________________________

R. Albert Mohler, Jr. is president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky.

==============================

**In the Shadow of Death—The Little Ones Are Safe With Jesus (Christian Post, 050108)

The photographs and images are now seared into our consciousness. One of the most troubling aspects of the disaster in Southeast Asia is the death of infants and young children. Moving at the speed of a jetliner, the walls of water fell on the young and the old alike—and so many of the youngest were simply swept away.

The death of the little ones poses anguished questions that reach to the depth of Christian faith. What happened to these young victims after death? Did they go to Heaven or to Hell?

That question is too pastorally loaded to be left hanging, only to be found at the end of this article. I am convinced that those who die in infancy and early childhood—along with the severely cognitively impaired—go to Heaven when they die. That is quite a claim, but it stands within the mainstream of orthodox Christian theology throughout the centuries, and I believe it is biblically and theologically sustainable.

In fact, I am hard pressed to imagine how any other answer can be given.

This is a question of emotional urgency for grieving parents, and it is a stone of stumbling for some who jump to hasty theological conclusions. The scope of the problem is huge, for untold millions of human beings have died at the earliest ages. Infant mortality still stands at several million babies a year. In the developing world, disease, famine, and abandonment take a heavy toll. Even in the most highly developed nations, armed with the latest medical technologies, thousands of infants die each year.

The best estimates out of Indonesia and Sri Lanka indicate that young children make up a disproportionate number of the victims of the tsunamis. Like Rachel in the Old Testament, anguished mothers weep for their children.

What is our answer to the question of the eternal destiny awaiting those children? My argument that these children are safe in the presence of Jesus Christ is based upon biblical evidence and theological reasoning. I cannot accept the glib and superficial assertions put forth by those who would simply offer assurance without adequate argument.

These infants are in Heaven, but not because they were not sinners. The Bible teaches that we are all conceived in sin and born in sin, and each of us is a sinner from the moment we draw our first breath. The doctrines of original sin and total depravity do not spring from some speculative theological imagination, but from the clear teaching of Scripture. There is no state of innocence, and these babies cannot enter Heaven unless the penalty for their sin is provided by the atonement of Jesus Christ.

These infants are in Heaven, but not because everyone is in Heaven. The Bible presents us with a stark picture of two destinies for humankind. Those who are in Christ, who have been redeemed by the blood of the Lamb, will be in Heaven. Those who are apart from Christ will be in Hell. Hell may be a despised concept—rejected by the theological modernizers—but it will not disappear, and its horrors await those who die without Christ. Jesus warned sinners to fear Hell, and the Bible warns that we must flee the wrath that is to come. Universalism is just not an option for any Christian who believes the Bible. Those who deny Hell deny the authority of Christ.

These infants are in heaven, but not because any of them were baptized. The practice of infant baptism has led to multiple theological confusions, and the death of infants is often one of the points of greatest bewilderment. Most of the early church fathers simply assumed that baptized infants who die in infancy go to Heaven, while unbaptized infants do not. These significant Christian leaders and thinkers, including figures such as Ambrose of Milan and Augustine of Hippo, taught the doctrine of baptismal regeneration—a belief still held by the Roman Catholic Church and most Eastern Orthodox churches. Among Protestants, Lutherans hold to a form of baptismal regeneration and some sacramentalists in other denominations also lean in that direction. According to this logic, infants are saved because they have been baptized and have thus received the gift of salvation. There is simply not a shred of biblical support for this argument. What these churches call infant baptism cannot help us in framing our argument. There is no biblical foundation for arguing for the salvation of infants from baptism, or for positing the existence of “Limbo” as a place of eternal suspension for unbaptized infants.

So, how can we frame an argument that is true to Scripture and consistent with the Gospel? Before turning to Heaven, perhaps we should take a closer look at Hell. According to the Bible, Hell is a place of punishment for sins consciously committed during our earthly lives. We are told that we will be judged according to our deeds committed “in the body.” [2 Corinthians 5:10] Adam’s sin and guilt, imputed to every single human being, explains why we are born as sinners and why we cannot not sin, but the Bible clearly teaches that every person will be judged for his or her own sins, not for Adam’s sin. The judgment of sinners that will take place at the great white throne [Revelation 20:11-12] will be “according to their deeds.” Have those who died in infancy committed such deeds? I believe not, for they have not yet developed the capacity to know good from evil. No biblical text refers to the presence of small children or infants in Hell—not one.

Theologians have long debated an “age of accountability.” The Bible does not reveal an “age” at which moral accountability arrives, but we do know by observation and experience that maturing human beings do develop a capacity for moral reasoning at some point. Dismissing the idea of an “age” of accountability, John MacArthur refers to a “condition” of accountability. I most often speak of a point or capacity of moral accountability. At this point of moral development, the maturing child knows the difference between good and evil—and willingly chooses to sin.

The Bible offers a fascinating portrait of this truth in the first chapter of Deuteronomy. In response to Israel’s sin and rebellion, God condemns that generation of adults to death in the wilderness, never to see the land of promise. “Not one of these men, this evil generation, shall see the good land which I swore to give to your fathers.” [Deuteronomy 1:35]. But God specifically exempted young children and infants from this condemnation—and He even explained why He did so: “Moreover, your little ones who you said would become prey, and your sons, who this day have no knowledge of good and evil, shall enter there, and I will give it to them and they shall possess it.” [Deuteronomy 1:39] These little ones were not punished for their parents’ sins, but were accepted by God into the Promised Land. I believe that this offers a sound basis for our confidence that God deals with young children differently than He deals with those who are capable of deliberate and conscious sin.

Based on these arguments, I believe that we can have confidence that God receives all infants into Heaven.

Salvation is all of grace, and God remains forever sovereign in the entire process of our salvation. The Bible clearly teaches the doctrine of election, but it nowhere suggests that all those who die in infancy are not among the elect. Even the Westminster Confession, the most authoritative Reformed confession, states the matter only in the positive sense, affirming that all elect infants are received into Heaven. It does not require belief in the existence of any non-elect infants. Those who insist that all we can say is that elect infants are saved while non-elect infants are not, confuse the issue by assuming or presuming the existence of non-elect infants and leaving the matter there.

We must remember that God is both omnipotent and omniscient. He gave these little ones life, knowing before the creation of the world that they would die before reaching moral maturity and thus the ability to sin by intention and choice. Did He bring these infants—who would never consciously sin—into the world merely as the objects of His wrath?

The great Princeton theologians Charles Hodge and B. B. Warfield certainly did not think so. These defenders of Reformed orthodoxy taught that those who die in infancy die in Christ. Hodge pointed to the example of Jesus: “The conduct and language of our Lord in reference to children are not to be regarded as matters of sentiment, or simply expressive of kindly feeling. He evidently looked upon them as lambs of the flock for which, as the Good Shepherd, He laid down his life, and of whom He said they shall never perish, and no man could pluck them out of his hands. Of such He tells us is the kingdom of Heaven, as though Heaven was, in good measure, composed of the souls of redeemed infants.”

Charles Spurgeon, the great evangelical preacher of Victorian England, and John Newton, the author of “Amazing Grace,” added pastoral urgency to this affirmation. Spurgeon was frustrated with preachers who claimed to have no answer to this question, and he hurled judgment on anyone who would claim that infants would populate Hell.

In the end, we must affirm the Gospel of Jesus Christ and the full authority of Scripture. We trust the goodness, mercy, justice, and love of God. Whatever He does is right. Salvation is all of grace, and there is no salvation apart from Christ. All are born sinners, and those who reach the point of accountability and consciously sin against God will be judged and punished for their sins in Hell—unless they have come by grace to faith in the Lord Jesus Christ.

B. B. Warfield may have expressed it best when he beautifully affirmed, “If all that die in infancy are saved, it can only be through the almighty operation of Holy Spirit, who works when, and where, and how He pleases, through whose ineffable grace the Father gathers these little ones to the home He has prepared for them.”

Keep those words firmly in mind as you contemplate this great and often troubling question. The little ones are safe with Jesus.

________________________________________

R. Albert Mohler, Jr. is president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky.

==============================

**The Doctrine of the Virgin Birth Under Attack—Again (Christian Post, 041224)

[Editor’s Note—Every year, the secular left uses the Christmas season as an opportunity to take aim at Christian beliefs. Especially incomprehensible to them is the Bible’s teaching that Jesus Christ was born of a virgin. Case in point—the two major news magazines which have run cover stories in just the past few weeks on the doctrine. In the summer of 2003, Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times wrote an editorial claiming that belief in the Virgin Birth of Christ was inherently unintellectual. Dr. Albert Mohler answered Kristof in a series of three articles. This week, we are republishing those articles as a reminder of just how crucial the Virgin Birth is to the Christian faith.]

Nicholas Kristof must be a very smart man — but a very slow learner. A columnist for The New York Times, Kristof is a Harvard graduate and was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University. But when it comes to something as significant as the nature of Christianity, Kristof and his columns are dumb and dumber.

Back in March [2003], Kristof wrote a very strange column suggesting that his liberal media colleagues ought to give evangelical Christians a closer look. [see my article in WORLD] Not that they would like what they saw, mind you, but that the rising public influence of the evangelicals demanded media attention.

His argument came down to this: Evangelicals are strange people with radical religious beliefs that will do great harm to the nation, but they mean well and so let’s be nicer in opposing them to the death.

An exaggeration? Kristof acknowledged that he tends to disagree with evangelicals on almost everything. And he intends to oppose evangelical influence at every turn, because, “I see no problem with aggressively pointing out the dismal consequences of this increasing religious influence.”

On the other hand, Kristof called upon his liberal colleagues to drop their “sneering tone about conservative Christianity itself.” If only he had taken his own advice.

This past Friday [August 18, 2003], The New York Times ran another Kristof piece in its editorial section, and it’s a wonder to behold: Perhaps the worst opinion piece to run in that paper in years — and that’s really saying something. [see Kristof’s article]

In his new column, Kristof points to “the most fundamental divide between America and the rest of the industrialized world: faith.” Unlike the rest of the industrialized world (with the exception of South Korea), America is resolutely religious. Europe is overwhelmingly secular, with low church attendance and very little Christian influence in public life or politics. In America, on the other hand, more persons attend church than public sporting events, and both major political parties court the religious vote — just in different sectors.

This is not news, at least to anyone even moderately informed about the national character of the United States. One would have to have been locked in a monastery for the last thirty years to have missed the religious dynamic of America’s culture war, and even the most casual visitor to western or northern Europe would note its secularity. But the divide between Europe and America is not Kristof’s real concern. It’s the divide between “intellectual” and “religious” America.

Got that? Intellectual and religious are now opposing terms? What Kristof really means is a divide between secularist/liberal America and Americans who are conservative Christians. As “Exhibit A” for his case, Kristof chose the doctrine of the Virgin Birth of Jesus.

“The faith in the Virgin Birth reflects the way American Christianity is becoming less intellectual and more mystical over time,” he wrote. More mystical? Less intellectual?

According to Kristof’s reasoning, no intellectually credible person could believe that Jesus Christ was born of a virgin. As authorities on this he cites the likes of Hans Kung, a German theologian barred by the Vatican from teaching Catholic theology. Kung is a notorious liberal, who has called the Gospel narratives a “collection of largely uncertain, mutually contradictory, strongly legendary,” stories. Kristof is obviously unaware of the huge body of scholarship in support of the Virgin Birth. But, in all likelihood, he wouldn’t care anyway. Quoting Hans Kung on the Virgin Birth is like identifying Hugh Hefner as a spokesman for chastity.

Kristof cannot believe that so many Christians [he cites 91-percent] take the Virgin Birth to be true, “despite the lack of scientific or historical evidence.” Is he demanding an ultrasound?

There are several important divides in American life today, and Kristof inadvertently pointed to one closer than he thinks: the divide between the secular media elites and believing Christians. The media elite is tenaciously committed to a worldview steeped in anti-supernaturalism. Miracles are out, along with the whole idea that modern people should be bound in any way by a 2,000-year-old book.

This is the most important American divide. One the one side are secularists who honestly cannot believe that intelligent people can believe Christianity to be true. One the other side are those who have staked their lives — including their intellectual energies — on the truthfulness and authority of the Bible.

It’s too bad Nicholas Kristof didn’t take his own advice. Instead, he offered up a caricature so ludicrous that it’s hard to take it seriously. Have all the editors at The New York Times gone away on vacation? In the end, this sad column tells us all we need to know about the real worldview of the media elite. It’s not like we didn’t know already.

___________________________________________

R. Albert Mohler, Jr. is president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky.

==============================

**It Takes One to Know One—Liberalism as Atheism (Christian Post, 041124)

“It takes one to know one,” quipped historian Eugene Genovese, then an atheist and Marxist. He was referring to liberal Protestant theologians, whom he believed to be closet atheists. As Genovese observed, “When I read much Protestant theology and religious history today, I have the warm feeling that I am in the company of fellow nonbelievers.”

Genovese’s comment rang prophetic when Gerd Ludemann, a prominent German theologian, declared a few years ago, “I no longer describe myself as a Christian.” A professor of New Testament and director of the Institute of Early Christian Studies at Gottingen University in Germany, Ludemann has provoked the faithful and denied essential Christian doctrines for many years.

With amazing directness, Ludemann has denied the resurrection of Jesus, the virgin birth, and eventually the totality of the Gospel. Claiming to practice theology as a “scientific discipline,” Ludemann (who taught for several years at the Vanderbilt Divinity School) has sought to debunk or discredit the Bible as an authoritative source for Christian theology.

In his influential book Heretics (1995), Ludemann sought to demonstrate that the heretics were right all along, and that the Christian church had conjured a supernatural Jesus to further its own cause. In What Really Happened to Jesus (1995) he argued, “We can no longer take the statements about the resurrection of Jesus literally.” Lest anyone miss his point, Ludemann continued, “So let us say quite specifically: the tomb of Jesus was not empty but full, and his body did not disappear, but rotted away.”

Nevertheless, Ludemann argued that Christianity could be rescued from its naive supernaturalism by focusing on the moral teachings of Jesus. Later, Ludemann gave an interview to the German magazine Evangelische Kommentare in which he stated that the Bible’s portrayal of Jesus is a “fairy-tale world which we cannot enter.”

In that same interview he denied the sinlessness of Jesus, explaining that, if Jesus was truly human, “we must grant that he was neither sinless or without error.” The church, he argued, must give up its faith in the “risen Lord” and settle for Jesus as a mere human being, but one from whom much can be learned.

In later writings, Ludemann argued that Jesus was conceived as the product of a rape, and stated clearly that he could no longer “take my stand on the Apostles’ Creed” or any other historic confession of faith. He continued, however, to teach as an official member of the theology faculty—a post which requires the certification of the Lutheran church in Germany.

Gerd Ludemann’s theological search-and-destroy mission eventually ran him down a blind alley. As he told the Swiss Protestant news agency Reformierter Pressedienst, he has come to a new realization. “A Christian is someone who prays to Christ and believes in what is promised by Christian doctrine. So I asked myself: ‘Do I pray to Jesus? Do I pray to the God of the Bible?’ And I don’t do that. Quite the reverse.”

Having come face to face with his unbelief, Ludemann has now turned his guns on church bureaucrats and liberal theologians. Many church officials, Ludemann claims, no longer believe in the creeds, but simply “interpret” the words into meaninglessness. Liberal theologians, he asserts, try to reformulate Christian doctrine into something they can believe, and still claim to be Christians. He now describes liberal theology as “contemptible.”

Looking back on the whole project of liberal theology, Professor Ludemann offered an amazing reflection: “I don’t think Christians know what they mean when they proclaim Jesus as Lord of the world. That is a massive claim. If you took that seriously, you would probably have to be a fundamentalist. If you can’t be a fundamentalist, then you should give up Christianity for the sake of honesty.”

Professor Gerd Ludemann reveals much about the true state of modern liberal theology. One core doctrine after another has fallen by liberal denial—all in the name of salvaging the faith in the modern age. The game is now reaching its end stage. Having denied virtually every essential doctrine, the liberals are holding an empty bag. As Ludemann suggests, they should give up their claim on Christianity for the sake of honesty.

Professor Ludemann is now a formidable foe of liberal theology, but he is also one of its victims. He said that he plans to pick up his teaching career from a “post-Christian” perspective, now that he knows “what I am and what I am not.” Should his liberal colleagues attempt to remove him from the theology faculty as a “post-Christian,” Ludemann may respond with Genovese’s quip: “It takes one to know one.”

______________________________

R. Albert Mohler, Jr. is president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky.

==============================

Pope: God will never destroy world again (970216)

ROME (Reuter) — Pope John Paul II said Sunday that because God formed an alliance with man after the Great Flood at the time of Noah, God would never destroy the world again.

The pope made his comments while preaching at a Rome parish before heading to the Vatican for a week-long Lenten spiritual retreat during which he will make no public appearances.

In his homily the pope said that after the Great Flood, which the Book of Genesis says was inflicted as punishment for widespread sin in the world, God forged an alliance with Noah.

Noah and his family were the only humans allowed to survive because of their goodness, the Bible says.

“From the words of alliance between God and Noah, it is understood that now no sin could bring God to destroy the world he created,” the pope said.

Addressing thousands of pilgrims and tourists in St. Peter’s Square later, the pope asked Catholics to pray, fast and give to the poor during Lent. The 40-day penitential season began last Wednesday and ends Easter Sunday.

During the week-long spiritual retreat, the pope and Vatican officials will suspend most official activity while they take part in a program of prayer and reflection.

[KH: The pope forgot 2Pe 3:10. The promise of no destruction after the Flood was only for non-destruction by the flood only.]

=========================================

St Paul’s finds modern creed is beyond belief (970924)

CLERGY and worshippers at St Paul’s Cathedral are puzzled why an unauthorised, “politically correct” version of the creed, the universal statement of Christian belief, has been inserted into services without their knowledge or consent.

Surprised churchgoers at 11am Holy Communion found themselves saying the new creed, in which the word “men” was omitted and the description of Christ’s conception altered.

The Dean, John Moses, admitted yesterday that an error had been made and said that the creed, last used on Sunday, would appear in services no more. “It appears that, on this occasion, we have made a small mistake,” he said.

Canon Stephen Oliver, the precentor in charge of liturgy at St Paul’s and a member of the General Synod’s liturgical commission, decided to test the creed to discern any problems before it is debated again in the synod in November. Although the Dean was aware of his plans, St Paul’s Chapter was not consulted. The issue was debated by the chapter yesterday, when the canons agreed that it had been a “valuable experiment”.

Canon Oliver said: “We learnt valuable lessons from it. There are actually bigger issues around at the moment than this.” Canon Michael Saward said: “We don’t want to cause any trouble and we will go back to Rite A from the Alternative Service Book. The experiment was reckoned not to be the best thing for us to do. It was an entirely amicable debate.”

One worshipper, who asked not to be named, said he was surprised that an unauthorised change was made to a particularly sensitive feature of the liturgy in a cathedral regarded as the flagship of the Church of England. “It is a politically correct creed,” he said. “We were all most surprised to see it there.”

The creed is a modified version of the Nicene Creed, issued by the Council of Constantinople in 381. The new version is being examined by the General Synod of the Church of England for inclusion in a service book that will succeed the much-derided 1980 Alternative Service Book at the millennium.

The word “men” is omitted from the line “for us men and for our salvation”. Christ is said to become incarnate “of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary”, instead of by the power of the Holy Spirit “of the Virgin Mary”.

In the Church of England, any change to the liturgy must, under the law of the land, be thoroughly approved by church members through their elected General Synod before it can be used.

One of the catheral’s clergy said: “It is more of a confusion than a punch-up. Some of us are concerned to know what is going on. One or two members of the congregation have raised questions about it with me. They came up after the service and asked whether there wasn’t something funny about it.”

Authorised version

We believe in one God,the Father, the almighty... For us men and for our salvation he came down from heaven; by the power of the Holy Spirit he became incarnate of the Virgin Mary, and was made man...

We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son. With the Father and the Son he is worshipped and glorified. He has spoken through the Prophets.

Nicene Creed from the 1980 Alternative Service Book Rite A.

Unauthorised version

We believe in one God, the Father, the Almighty... For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven, was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary and was made man... We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son. who with the Father and the Son is worshipped and glorified, who has spoken through the prophets.

Nicene Creed used in St Paul’s, taken from Praying Together, prepared by the English Language Liturgical Consultation, 1988.

======================================

Last Supper clues challenge Easter week timetable (970407)

A LEADING biblical archaeologist claimed yesterday that new evidence had been uncovered which requires a drastic rewriting of the Easter week timetable to show that Jesus and his disciples shared the Last Supper three days -and not just a matter of hours -before his Crucifixion.

Father Bargil Pixner said the new theory explained the riddle that has long eluded Bible scholars as to why Matthew, Mark and Luke describe the Last Supper as a Passover meal, while John says that Jesus was crucified “just before” Passover.

Speaking yards from the spot where many Christians believe the meal was eaten in a large upper room (in a guest house long since destroyed) Father Pixner said: “Both timings were correct because they were based on different feast-day calendars.”

The Benedictine prior of the Dormition Abbey on Mount Zion bases his theory on excavations which he claims show there was an Essene community there whose inhabitants went by a solar calendar, which would have had the Passover meal eaten on the Tuesday of Passion Week in AD30, the year it is said that Christ died, rather than the Friday . “By recognising that Jesus shared that meal by the Essene date and not the temple priests’ or lunar date, we can properly understand the sequence of events,” he said.

If Jesus was arrested in the early hours of Wednesday, and died on Friday, then the trial against him lasted three days.” Father Pixner said that this “would make a great deal more sense of all the things that were supposed to have happened before he was crucified “at the third hour” -that is, around 9am on the Friday.

The Essenes, authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls, were Jewish purists who reacted against what they saw as the corruption of the high priests, and until recently were assumed to have lived mostly in small rural communities close to the Dead Sea.

In the face of scepticism from some rival scholars who have denied the Essene presence in the Holy City, Father Pixner has used radar and sonar studies to support his theory since it was first raised in his book, With Jesus in Jerusalem, and has applied to the Greek Orthodox Church for permission to excavate in a spot which he says will provide “definitive proof”.

======================================

Church’s liturgy to include exorcism and healing (980615)

PRAYERS for exorcism and healing are to be introduced into the Church of England’s liturgy. The charismatic-evangelical revival in the established Church has led to widespread use of healing services and church authorities are anxious to regulate them.

A new liturgy of “wholeness and healing” will be debated by the General Synod in York next month. The new services will include provision for healing the sick, with a laying-on of hands where the priest prays for a sufferer to “receive Christ’s healing touch to make you whole”.

Prayers “for protection and deliverance” from “the enemy” (the Devil), however, are likely to prove more controversial. At present, the Church’s official ministry for deliverance, a term used to refer to exorcism, is carried out by priests authorised by a bishop. The conditions under which a house or a person can be exorcised are strictly controlled, and special permission must be obtained from the diocesan bishop.

The new liturgy states that permission must still be granted by a bishop, but for the first time it includes prayers “where it would be pastorally helpful to pray with those suffering from a sense of disturbance or unrest”.

For the deliverance of a place or building, the liturgy states: “Visit, Lord, we pray, this place and drive far from it all the snares of the enemy.” For a disturbed person before sleep, it pleads for protection from the Cross, “which is mightier than all the hosts of Satan”, from evildoers, evil spirits, foes visible and invisible and “from the snares of the Devil”.

The liturgy also includes three rites of healing, for use at a mass diocesan event, at a parish church and with individuals. According to the introduction, an individual’s physical, social, emotional and spiritual well-being are closely connected. “The gospels use the term healing for physical healing and for the broader salvation that Jesus brings,” it states. The liturgy rejects any link between sickness and sin, and also urges that prayers for healing should not involve any rejection of conventional medicine.

The services are part of the new liturgies being debated by the synod and which will replace the 1980 Alternative Service Book at the millennium. New versions of the Lord’s Prayer, the eucharist, the marriage, initiation and funeral services will also be hotly debated.

======================================

Many Americans still wonder about the nature of Jesus (Star Tribune, 040104)

Thomas Hargrove and Guido H. Stempel III, Scripps Howard News Service

Who was Jesus?

Americans, for the most part, believe in the historical reality of the itinerate Jewish rabbi who nearly 2,000 years ago proclaimed the coming of the kingdom of God to his friends and neighbors in Judean towns along the Sea of Galilee.

A survey of 1,054 adult residents of the United States conducted by Scripps Howard News Service and Ohio University found that 75 percent “absolutely believe” that Jesus was a real person. Sixteen percent said they “mostly believe” in his historical reality, 5 percent “do not believe” and 4 percent were uncertain.

But what Americans accept about Jesus is much more complex.

Nearly 20 percent don’t believe that Jesus was born to the Virgin Mary, one of the central points in the traditional story but the most disputed idea in the survey. Sixty percent said they “absolutely believe” Jesus was born to a virgin, 16 percent mostly believe and 5 percent are uncertain.

Americans have slightly more confidence that Jesus “died and physically rose from the dead,” with 63 percent saying they “absolutely believe” this central theme of the Easter story. But, surprisingly, adults in the poll were more likely to conclude that “Jesus was the son of God” and that “Jesus was divine” — for which absolute belief was at 69 percent and 67 percent, respectively — than to believe the biblical accounts of his birth and death.

The survey results prompted deep disagreement among prominent U.S. theologians.

“This shows a glaring inconsistency in the American mind to hold that Jesus was divine but that he did not rise from the dead or was born of a virgin,” said the Rev. Al Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky.

“Americans are growing increasingly comfortable with a cafeteria-line-style spirituality in which they pick and choose whatever doctrines seem pleasing and leave those that seem distasteful,” Mohler said. “The denial of the virgin birth eventually comes as a part of a wholesale denial of orthodox Christianity itself.”

Marcus Borg — distinguished professor of religion and culture at Oregon State University and author of the bestseller, “Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time” — said the poll shows that many Americans are reevaluating past, literal interpretations of Jesus. Borg, an Episcopalian, believes Jesus is the revelation and incarnation of God, but does not believe in the virgin birth or physical resurrection.

“There are a growing number of Christians who understand the story of Jesus’ birth and resurrection as metaphoric and symbolic,” said Borg. “There are millions of Christians and former Christians who simply can’t be biblical literalists or absolutists. They want to take the Bible seriously, but not literally.”

The study found that belief in the virgin birth varied considerably among different groups. Men were significantly less likely to believe this than were women, and residents of Southern and Midwestern states embraced the doctrine of virgin birth at a higher rate than residents of the Northeast or West.

Despite the Roman Catholic Church’s historical emphasis on the theological importance of Mary, Catholics in the poll were somewhat less likely than Protestants to believe in the virgin birth. Theologians attributed this to the doctrine in many Protestant churches that the Bible must be accepted as literal truth.

Adults with children were much more likely to believe in the virgin birth than were adults who have never been parents. This reflects a well-documented trend in which adults resume churchgoing habits of their youth when raising their own children.

Although many Americans discount some of the claims about Jesus, both liberal and conservative theologians point to the overall finding in the poll that most Americans still believe in Christianity’s core traditions: that Jesus was the physical incarnation of God and that he experienced bodily resurrection following his crucifixion. Fifty-one percent said they believed all five attributes of Jesus tested in the study.

“Putting all of this in context, even in this secular age, a great percentage of Americans get it right when they reveal their most fundamental understanding of who Jesus is,” Mohler said.

But liberal and conservative theologians also noted that a significant number do not strictly adhere to the Nicene Creed, the statement of faith first adopted by Christian bishops in 325 A.D. Most Americans have recited that famous creed beginning with: “We believe in one God, the Father, the Almighty, maker of heaven and Earth. . . .”

Few theologians dispute that Jesus himself believed that he was “the son of God” and told his followers that he had a divine revelation of this following his baptism by John in the Jordan River. But it took nearly three centuries for the church to conclude that Jesus was “God from God . . . of one being with the father” — the words of the Nicene Creed.

The survey was conducted at the Scripps Survey Research Center at Ohio University. Residents of the United States were interviewed by telephone from Oct. 20 through Nov. 4 in a study funded by a grant from the Scripps Foundation.

The overall poll has a 4 percentage point margin of error, although the margin increases when examining attitudes among smaller groups within the survey.

==============================

The ‘Openness of God’ and the Future of Evangelical Theology (Christian News, 041119)

[Editor’s Note: The Evangelical Theological Society is meeting this week in San Antonio, Texas. The following article was first published last year during the ETS meeting, when the main topic of concern was how to deal with a theological movement known as “Open Theism.” One year later, this issue is no less important.]

Theology will be front and center at this week’s meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society in Atlanta, Georgia. This is not a year for business as usual, for the society will be confronting charges brought against two of its members. Given the nature of the charges, one or both of these individuals may be removed from membership in the society. Why? The answer to that question points to one of the most significant controversies facing contemporary evangelicals.

The theologians in question, Clark Pinnock and John Sanders, are both proponents of a theological movement known as “Open Theism.” In sum, open theists argue for a new model of understanding God’s knowledge—a model that insists that true human freedom requires that God cannot know human decisions in advance.

Actually, open theists deny God’s omniscience in matters that go beyond human decisions. The worldview promoted by open theists is based in a high degree of confidence that God will be able to direct the future in a general way, but open theists deny that God can possess infallible and comprehensive knowledge of the future. In essence, God is waiting with the rest of us to know how any number of issues will turn out.

Promoted by Pinnock and Sanders, along with other popular theologians such as Gregory Boyd, the open theists present a more user-friendly deity, less offensive to many moderns. This new model of God, based in something like what Clark Pinnock calls “creative love theism,” redefines the God of the Bible and denies the classical understanding of God’s sovereignty, knowledge, and power.

Bruce Ware, a careful critic of open theism, summarizes the movement in this way: “This movement takes its name from the fact that its adherents view much of the future as ‘open’ rather than closed, even to God. Much of the future, that is, is yet undecided, and hence it is unknown to God. God knows all that can be known, open theists assure us. But future free choices and actions, because they haven’t happened yet, do not exist, and so God (even God) cannot know them.”

As Ware explains, “God cannot know what does not exist, they claim, and since the future does not now exist, God cannot know it.” Most importantly, open theists argue that God cannot know what free creatures will choose or do in the future. Thus, “God learns moment-by-moment what we do, when we do it, and His plans must constantly be adjusted to what actually happens, in so far as this is different than what He anticipated.”

In two important books, God’s Lesser Glory: The Diminished God of Open Theism and Their God is Too Small [both from Crossway Books], Ware provides a responsible and careful analysis of the open theists’ arguments. Ware takes these thinkers seriously, and judges their argument by the Bible. In so doing, he concludes that the open view of God “poses a challenge to the evangelical church that is unparalleled in this generation.”

The doctrine of God is the central organizing principal of Christian theology, and it establishes the foundation of all other theological principles. Evangelical Christians believe in the unity of truth. Therefore a shift in the doctrine of God—much less of this consequence—necessarily implies shifts and transformations in all other doctrines.

The open theists point to biblical passages that speak of God repenting or changing His mind. Rather than interpreting those passages in keeping with the explicit statements of Scripture that God knows the future perfectly, the open theists turn the theological system on its head, and interpret the clear teaching of Scripture through the narratives—rather than the other way round.

They also counsel that their “open” view of God is more helpful than classical Christian theism. After all, they advise, it allows God “off the hook” when things do not go as we had hoped.

In a now notorious example, Greg Boyd tells of a woman whose plans for missionary service were ruined by the adultery of her husband and subsequent divorce. This woman, Boyd relates, went to her pastor for counsel, asking him how God could have led her to have married this young man, only to see the marriage end in adultery and disaster. This pastor [presumably Boyd himself?] assured the woman that God shared her surprise and disappointment in how the young man turned out.

Most evangelicals would be shocked to meet this updated model of God face to face. Nevertheless, subtle shifts in evangelical conviction have been undermining Christianity’s biblical concept of God.

Belief in God’s absolute knowledge has united theologians in the evangelical, Catholic, and Orthodox traditions. Denials of divine omniscience have been limited to heretical movements like the Socinians. Even where Calvinists and Arminians have differed on the relationship between the divine will and foreknowledge, they have stood united in affirming God’s absolute, comprehensive, and unconditional knowledge of the future.

Several years ago, a major study of religious belief revealed just how radically our culture has compromised the doctrine of God. Sociologists asked the question, “Do you believe in a God that can change the course of events on earth?” One answer, which became the title of the study, was “No, just the ordinary one.” That is to say, modern men and women seem to feel no need to believe in a God who can change the course of events on earth—just an “ordinary God” who is an innocent bystander observing human events.

Measured against the biblical revelation, this is not God at all. The God of the Bible is not a bystander in human events. Throughout the Scriptures, God speaks of His own unlimited power, sovereign will, and perfect knowledge.

This model of divine sovereignty is explicitly denied by the open theists. As Clark Pinnock explains, “God is sovereign according to the Bible in the sense of having the power to exist in himself and the power to call forth the universe out of nothing by his Word. But God’s sovereignty does not have to mean what some theists and atheists claim, namely, the power to determine each detail in the history of the world.”

The obvious question to ask at this point is this: Just which details does God choose to determine? Pinnock’s “creative love theism” is, regardless of his intentions, a way of taking theism out of theology. This God is so redefined that He bears little resemblance to the God of the Bible.

Pinnock and his colleagues argue that evangelicals must transform our understanding of God into a model that is more “culturally compelling.” Where does this end? The culture gets to define our model of God?

Open theism does not stand alone. Acceptance of this model will require a complete transformation of evangelical conviction. A redefinition of the doctrine of God leads immediately to the redefinition of the Gospel. A reformulation of our understanding of God’s knowledge leads inescapably to a reformulation of how God relates to the world.

Indeed, some have gone so far as to call for an “evangelical mega-shift,” that would completely transform evangelical conviction for a new generation. Even granting the open theist the highest motivations, the result of their theological transformation would be unmitigated disaster for the church.

The late B.B. Warfield remarked that God could be removed altogether from some systematic theologies without any material impact on the other doctrines in the system. My fear is that this indictment can be generalized of much contemporary evangelical theology. As the culture draws to a close, evangelicals are not arguing over the denominational issues that marked the debate of the twentieth century’s early years. The issues are now far more serious.

Sadly, evangelicals are now debating the central doctrine of Christian theism. The question is whether evangelicals will affirm and worship the sovereign and purposeful God of the Bible, or shift their allegiance to the limited God of the modern mega-shift.

At stake is not only the future of the Evangelical Theological Society, but of evangelical theology itself. Regardless of how the votes go in Atlanta, this issue is likely to remain on the front burner of evangelical attention for years to come.

The debate over open theism is another reminder that theology is too important to be left to the theologians. Open theism must be a matter of concern for the whole church. This much is certain—God is not waiting to see how this vote turns out.

____________________________________

R. Albert Mohler, Jr. is president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky. For more articles and resources by Dr. Mohler, and for information on The Albert Mohler Program, a daily national radio program broadcast on the Salem Radio Network, go to www.albertmohler.com. For information on The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, go to www.sbts.edu. Send feedback to mail@albertmohler.com. Original copy from Crosswalk.com.

==============================

The Faith vs. the Force: The Mythology of ‘Star Wars’ (Christian News, 041119)